On October 5, 2023, Sylvain Berneron, Chief Product Officer of Breitling, introduced the Mirage, the flagship model for his new “Berneron” brand. There will be two versions of the Mirage — the Sienna (with a yellow gold case) and the Prussian Blue (with a white gold case) — with annual production limited to 12 samples of each version, for a total of 24 watches per year. Over the last month, Berneron has allocated all 72 of the watches to be produced in the first three years.

In our in-depth conversation with Sylvain, he explains why he created the Berneron brand, the inspirations for the design of the Mirage and his current plans for the Mirage and for the Berneron brand.

Specifications for the Mirage are included at the end of this posting.

1. Let’s start at the very beginning of your career as an artist. You have referred to the lessons that you learned from your mother, who was an artist. Can you tell us how she influenced your approach to art and design.

Sylvain Berneron — My mother passed away when I was 17, but in my years with her, she provided me with a strong artistic background. I am referring specifically to fine art — sculpture, painting, watercolors, pen drawing, etc. My mother was a very good painter and then she infused this artistic sense in me.

She never made a living from art, because at the time, painting where she grew up was not considered a decent way of living. She painted directly on the walls and not on a canvas. I was raised by a true artist; she was someone who had to create art. She had to paint. This was an energy or an urge that she had to express through her art. My mother, if she would not paint, if she would not let it go out, she would get depressed. It’s hard to explain. I have no other way to say it, but it’s not a choice, unfortunately. My mother didn’t wake up one day and say, “Oh, I have to paint in the living room.”

I am unfortunately the same way, which is why I’m stupid enough to spend 15 years of savings to make a bent watch rather than to buy a house like anybody with a normal brain would do. Just like someone I assume who needs to sing to be alive or who needs to dance. In my family, we have to draw.

So my mother would paint abstract and she would paint very organic compositions, always on the walls. We had 15 living rooms in 17 years, because she would repaint. And I’m not talking about painting blue, orange or green flat walls. I’m talking about abstract compositions and illustrations and perspective and light and shadows and proper artistic works.

She also helped me develop confidence in my drawing. I think just like singing or dancing, when you start to practice the craft, you are often very shy to dance or to sing in front of others. The same goes for drawing. When you start drawing you’re often very shy about showing it to others. My mother not only taught me how to get the confidence to show my work to others, she also taught me how to explain what I did and why I saw it was important and how I could — to some extent — defend what I had drawn.

My mother taught me that any artistic endeavor is about transforming a constraint or restriction into an opportunity. It doesn’t matter which medium we choose. This is the mindset of all the big artistic currents over history, whether it is cubism, impressionism, dada-ism, Renaissance, whatever. All these guys were fighting constraints, whether they were political, technical, philosophical or whatever. Art challenges us to move beyond these restraints.

So when you make art, by definition, you are crossing a line. You are offending somebody. That’s the whole purpose, that’s the whole vibration of doing that. That’s the reason why I twist the sector dial and make asymmetric watches.

2. How have these lessons from your mother translated from the world of fine art to the world of industrial design?

Sylvain Berneron — To be clear, I understood from my mother that, on a philosophical level, any artistic endeavor remains more noble than an industrial design project. But since I began working in industrial design, I have felt that drawing just for the sake of drawing is not enough. I feel a great sense of joy when I draw something with the intention that I’m going to build it later.

This is what moves my heart, my motivation, my joy. It’s using the drawing skills to plan something, to try to emulate how the final piece will look and feel, and then to see how we will be able to assemble it and how it will work. Now, I am using art and drawing as levers, skills to create the final product.

3. You began your career as a designer in the transportation industry, working for brands such as BWM and Ducati. Why did you move from designing cars and motorcycles to designing watches?

Sylvain Berneron — I quit the car industry because it was no longer aligned with my values. For example, I might be asked to facelift a car or a motorcycle, and that means making a pair of new bumpers just to push more consumption, when in fact, it’s the same car. The designer is used as a weapon to fuel consumption. And we all know the crazy impact of the construction industry and the automotive industry, so designing cars was no longer aligned with my personal values.

I should also mentioned that the car industry is a lot stiffer in terms of creativity because of the impact of regulations — crash regulations, environment regulations, etc. The range of freedom for a designer is actually very restricted in the car industry. The days where the car designers were making the Lamborghini Countach and Muiras and Ferrari Testarossas are gone and they will never come back.

4. Why was the watch industry a good destination for you?

Sylvain Berneron — Watchmaking had been a great hobby of mine that I received from my father and my uncles who are amateur watch collectors. Ten years ago, I realized that the watch industry would be a much more satisfying medium to express myself.

In the watch or jewelry industries, since we do not have all these regulatory requirements, you can still go completely mad, for example, and do an MB&F HM 9 or Berneron Mirage or Cartier Crash or you name it. The spectrum of creative freedom is still intact and will remain so. So this seemed like a much more efficient medium to express myself.

5. For a designer, what elements are common to the transportation industry and the watch industry, and what factors make the work different in the two industries?

Sylvain Berneron — The background is the same in the sense that a watch, a motorcycle and a car, all are technical objects, which means the designer needs to understand all the technical aspects of what he is creating. The industrial designer also needs to understand the manufacturing process. He also needs to understand where to allocate the money in an object in order to maximize the impact of the cost of production versus the perceived value to buyers. So overall, the mindset and the approach is the same.

Of course, the fundamental difference between designing cars or motorcycles and designing watches or jewelry is the scale. With watches, I would say that it takes a good year to get the eye trained properly, to be able to tell the difference between 0.2 and 0.3 millimeters, for example. On a car you may be dealing in centimeters, which then becomes a mile on a watch. A millimeter on a watch is gigantic as we all know. So that’s the very pragmatic side of designing these different types of technical objects. Of course, there is also a more romantic side to designing watches and jewelry.

6. In designing for established brands like BWM, Ducati and Breitling, how do you think about the heritage of the brand?

Sylvain Berneron — I believe that designers are here to serve the brand. A designer is not here to please himself, but he’s here to understand the tone of voice and legacy of the brand, in order to perpetuate its heritage into the future. So for the companies that I have worked with, I always took a considerable amount of time to understand the history of the brand. Fred Mandelbaum can tell you how much time I spent with him so that he could educate me on Breitling so that whatever I would draw would actually be a new page of the Breitling book and not Sylvain coming in and pouring his own taste onto Breitling.

In a sense, the heritage of a brand becomes a restriction on the designer, but this is a more natural and acceptable type of restriction than trying to satisfy crash testing or fuel efficiency regulations in the transportation industry.

7. Can you summarize the key factors in watchmaking by the big brands that moved you to create your own brand?

Sylvain Berneron — Again, the comparison to the car industry is interesting. When I was in the car industry, I understood that you can’t raise or lower the bumper, because the car were to hit another car on the road, you will do a lot more damage. And if you increase the drag, fuel efficiency will suffer. So these technical constraints drive the aesthetic constraints. I fully understand this, because we know why we do it. The engineers will usually have a good reason of why they will basically diminish your design, but at least you can respect the trade-off.

In the watch industry, the technical constraint is basically zero, because the object is not really precise, let’s face it. If we were using watches as precision tools, all of us would be using atomic clocks. So by definition, we are creating what I like to call “technical jewelry”. That’s what we do. So if we start from that analysis, we should not have any rules to follow because it’s just fucking jewelry. You don’t go to a jewelry designer and tell him, “Oh, these shapes are forbidden. You can’t use these colors.” No, you don’t because it’s meant to be an artistic expression.

The big watch brands are extremely stiff. I think the entire industry is still in some sort of a post-traumatic state of mind from the 1970s, that maybe not everybody in the industry realizes that the “quartz crisis” is over. For utmost accuracy, we can rely on quartz watches or even our smart phones. To the extent that today’s watches belong in the jewelry category, the brands should be a lot more creative and even audacious.

8. How does this conservatism or stiffness in the watch industry manifest itself, in practical terms?

Sylvain Berneron — In the watch industry, you still find today, as a designer — because I know a lot of designers in the industry — we all have what we call our “demons” for the brand we work with. Depending on the brand you work for, you will have a restricted set of colors or you will have a restricted set of dimensions and, to some certain extent, you will be allowed to use certain movements, but not others.

I’ve been told for 10 years, “Don’t use manual wind movements because they don’t sell. Do not break symmetry because it becomes extremely divisive. Do not shrink the size, because a watch below 40 millimeters is not a man’s watch”, etc. Frankly, these are all preconceived rules based on past trends, based on sales numbers. That’s all they are.

I think that if the watch industry was not so restrictive, I would not have gone so far to create my own brand. This stiffness fueled my desire to really break the wall and go as far as I could then, because then I started to ask myself the question, “Okay, if we didn’t have these restrictions, what could watches be?” The rules in the watch industry fueled this need for me to create the Berneron brand.

It’s like a kid when you go in a house and the owner says, “You can go anywhere in the house, but you must not open that door. Do not open that door. No matter what you do, you can do everything, but do not open that door.” And if you keep repeating this long enough, you can be sure that at some point the kid will open the door. It almost becomes an order, a vital necessity to know what’s behind the door.

I have been told so many times, “Sylvain, forget about that. Don’t do it. Don’t do it.” Yet, my inner guide would tell me that there could be something to explore behind these doors that I was told not to open. For example, breaking symmetry is disturbing for some people. And the question quickly became for me, “What happens if you have zero points of symmetry to compare? What would that watch look like?”

9. Can you tell us about your arrangement with Breitling that allowed you to begin working on the Berneron brand as a “side hustle”.

Sylvain Berneron — So I’ve been working for big brands for 15 years in the transportation and watch industries, and I never had the chance to work on a higher philosophical vibration, on this artistic level that I just described previously. And at some point I felt the need, the really strong need, so I had to do it, which is why I had the discussion with Georges [Georges Kern, CEO of Breitling]. I started the discussion probably three years ago and three years down the line, I am contractually allowed to spend 50% of my time on Berneron, while being Chief Product Officer for Breitling at the same time.

This arrangement is a huge, huge privilege. I am very grateful for this opportunity that Georges granted me. The watch industry is still an extremely conservative and stiff industry in the way it operates, and I hope that maybe I can be some sort of a little icebreaker to show that it is possible to do a good job in a big company and to have your own label on the side.

My peers in the fashion industry have been taking this approach for almost two decades now. You have multiple fashion creative directors that have their own labels and no one complains. Virgil Abloh continued to run his own Off-White brand even after being named head of menswear at Louis Vuitton. He said that Off-White was for the 17-year-old version of himself, while Louis Vuitton was for the 37-year-old version. As designers grow older, perhaps they need different brands as outlets.

This has not been an acceptable approach in the watch industry, and so I hope that my case will prove that this can be good for the big brand and also good for the designer.

10. What were the practical and financial commitments that were required to create the Berneron brand and to launch the Mirage?

Sylvain Berneron — I started working for BMW when I was 19, as an intern, and my dad told me, “Save 30% of your salary every month and in 10 or 15 years you’ll be able to buy a house for your family.” So I did do the saving exercise, and when I reached the point where I could go to a bank and buy one of these expensive houses in Switzerland, I decided to pull back and to make a watch project. So I poured 15 years of personal savings — which is all our money — into this project.

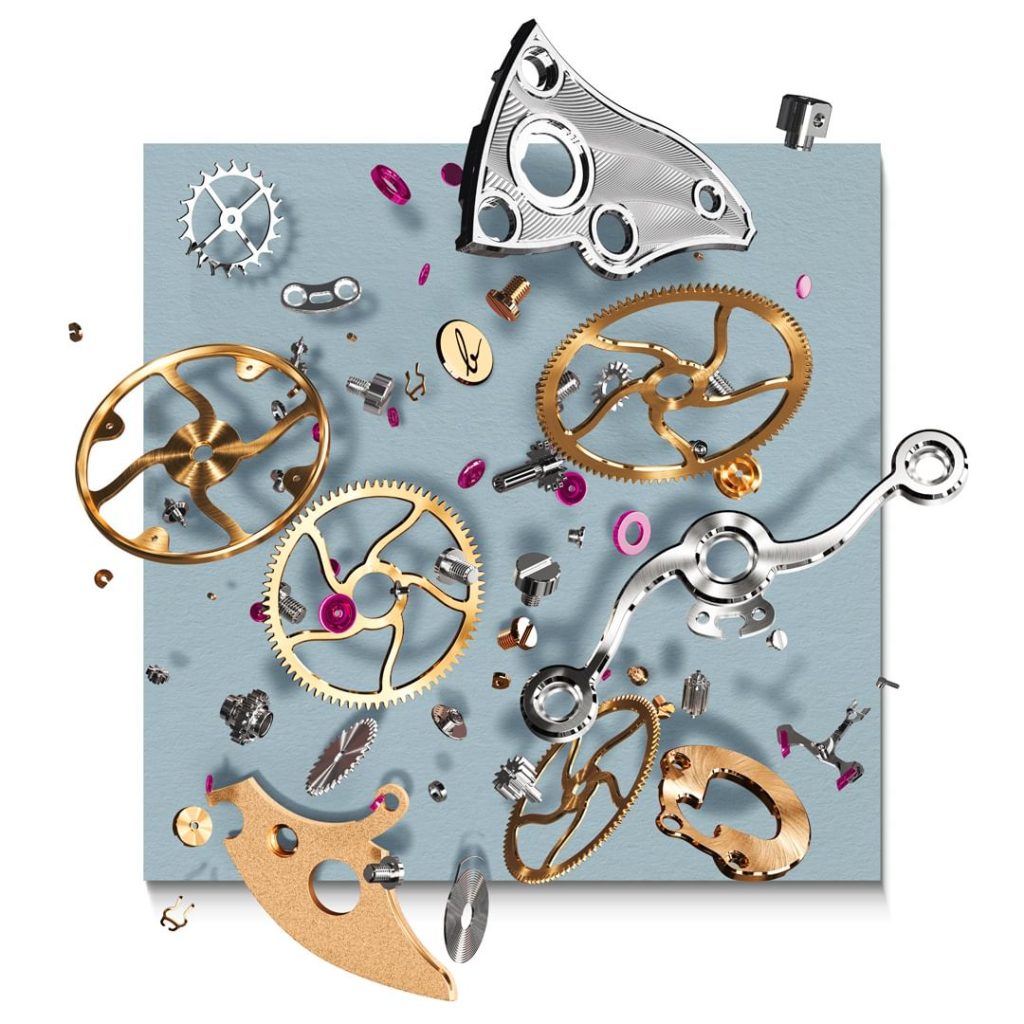

I should also add that doing shaped movements with an extensive use of precious metal adds additional risk to the project. From the industrial and financial perspective, you want to decouple the risk of your movement investment from your risk of your aesthetic investment, which is the casing. So that if one or the other goes wrong, you can hope to save half of your investment. For example, you have a shitty movement, but the collection works well, you can swap the movement for another one. Or vice versa. For the Mirage, it’s really all-in, because not only did I make a shaped movement that is absolutely entirely paired with the case, and on top of that I make it in gold.

The risk involved is massive, even if it’s at a tiny scale. All this means that nobody would dare to finance such a project, and I would not be comfortable either to take someone else’s money to take that much risk. So I realized that I had to develop the Mirage using my private funds.

This has required an incredible commitment from Marie-Alix, my wife. She could have asked me, “Oh, well, I’d rather to have a house for family rather than you spending the money on a watch project.” But we are married for a reason and she knows that I would be a happier man even with a failing watch project rather than a house and me keep fantasizing about making something.

On the practical side, obviously getting such a project off the ground while performing an important job for Breitling means I’ve been working seven days a week for the past two years. So that also is a big commitment because obviously my friends and my family and my wife have to deal with my absence for the times that I have to put behind the computer and on the drawing board and visiting suppliers. So it is indeed a very deep and full commitment in order to make it happen.

Designing the Mirage

11. Can you tell us what principles guided you in developing the Mirage?

Sylvain Berneron — These principles were relatively simple. I wanted to design a watch with no restrictions and no compromises, so everything had to be done the right way. This also suggested that the costs should not be a real constraint on the project and that timeline for producing the watches would not be critical.

12. Why did this approach lead you to start with the movement?

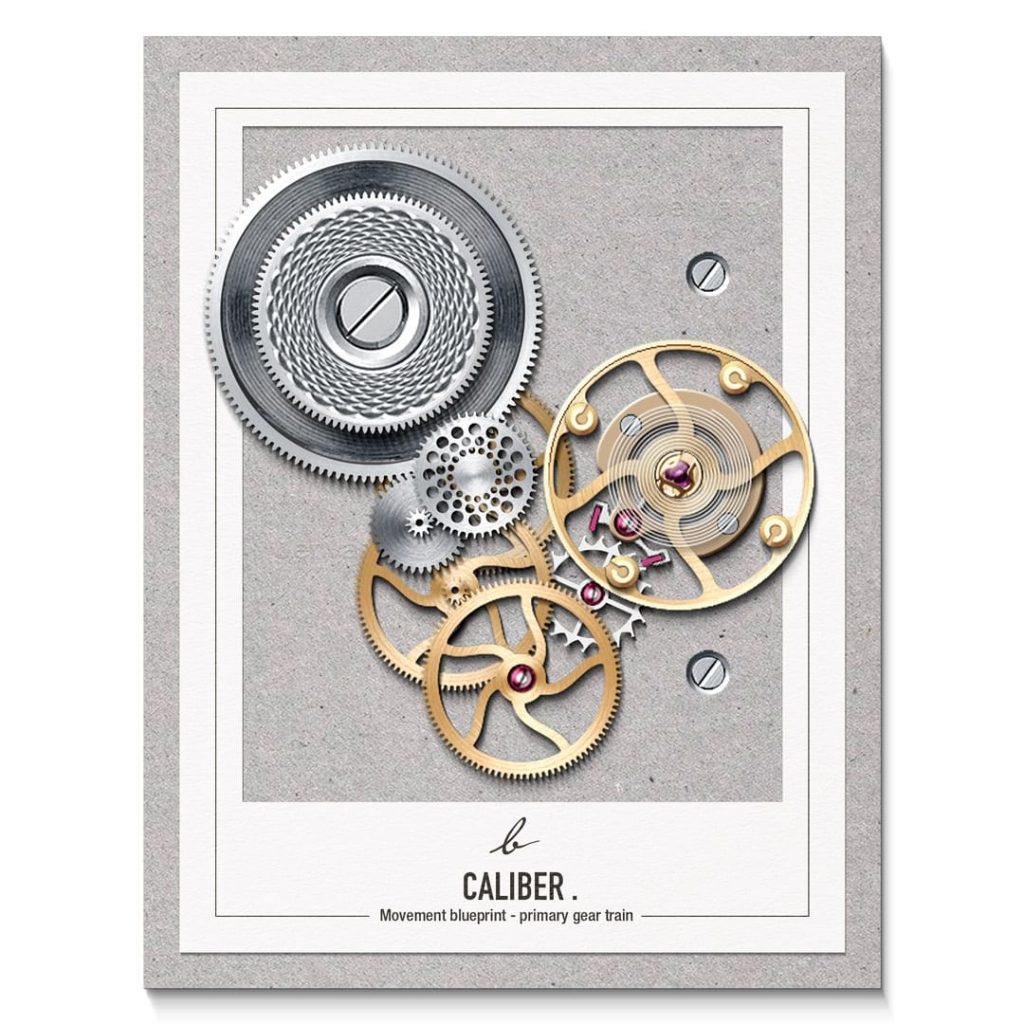

Sylvain Berneron — Over the years, I developed many movements in the watch industry. But I’ve always been frustrated on the compromises we have to make because it’s always a trade-off between proportion and efficiency. So, either you have the very big movements in which the watchmaker had the space to play — so that he could use a big barrel and a large balance wheel, for example — with whatever space he needed to have a very well-made movement. And on the other side, the designer will struggle to work around this large movement because it would drastically impact the proportions of the piece.

Or if you go to the other extreme, and you take these shaped watches, for example, the work of Rupert Emmerson (for Cartier) or Gilbert Albert (for Patek), these guys went full-on doing free shape cases, with beautiful designs. But in the end, the watchmaker for their watches has been heavily penalized because he has to deal with whatever space is left inside to make sure that the piece could still at least show you the time. You end up with these watches that are often regarded in our circle of collectors as “fashion watches”, because they have very little watchmaking substance in them, or even none at all. These fashion watches have basic movements, with low performance, low power reserves, no finishing and a closed case back. This is a very basic level of watchmaking, even if it can be a nice piece of jewelry on the wrist.

13. How did this limitation of the historic shaped watches affect the way that you approached the design of the Mirage?

Sylvain Berneron — I really like technique, I like craftsmanship. So, for me, it was a must to offer a decent, if not top-notch, watchmaking substance in the product, into whatever watch that I would start to do. Which is why, when I started to draw the Mirage, and it’s actually part of why it’s called the “Mirage”, it’s because I refused to make the typical compromises that you have to do when you start any movement project. What if we do all these things that watch designers are told not to do? Will it become an illusion, like a mirage, or unrecognizable as a watch, or perhaps it will become an even more beautiful watch?

So I asked myself the question, “Okay. Is there a way that I could not have to choose between the appearance and performance of the movement? What if I wanted a movement that would be both made of precious metal, very slim, very elegant on one hand, so that I could have a good proportion on the wrist, and on the other side, what if I still wanted a strong performance that is not compromised?”

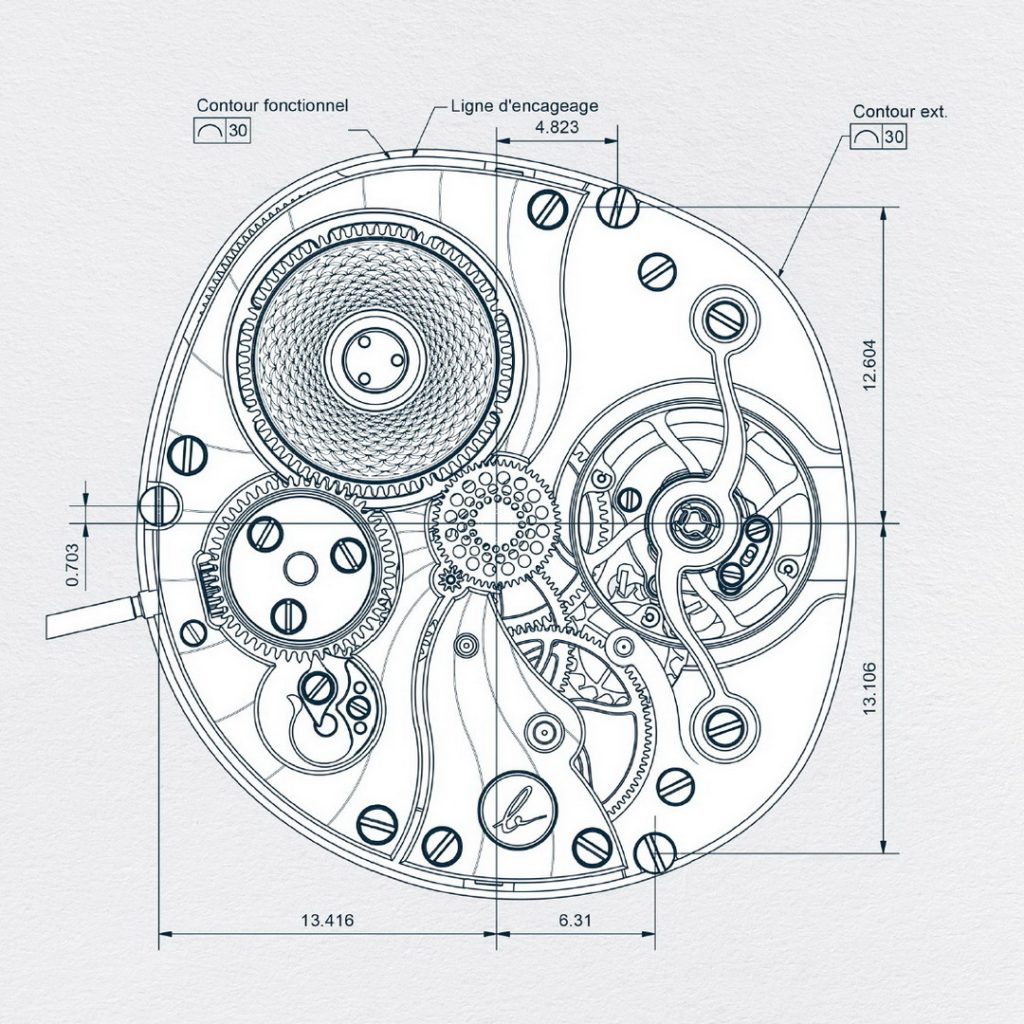

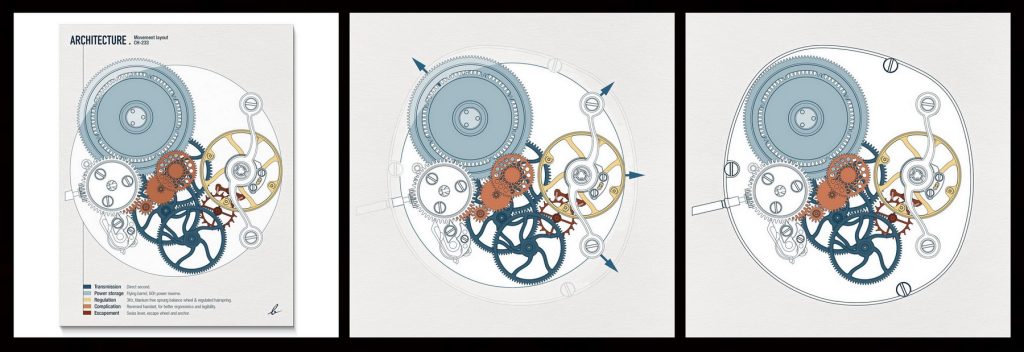

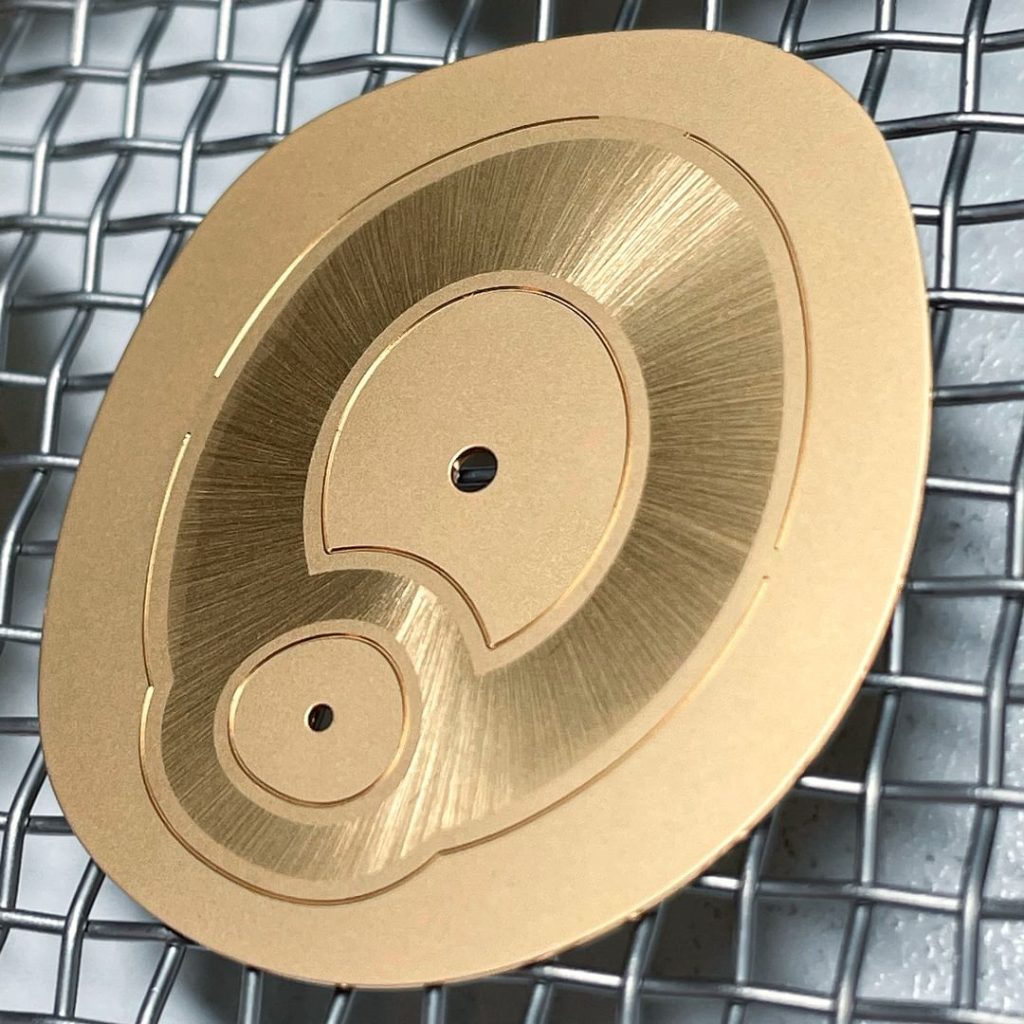

I believe that I have achieved this objective by letting the movement go free. So, the barrel took the size that it required to perform as we wanted. The crown had to be pushed down in order to leave space for the barrel. The small second took the place it needed to grow up to the center wheel. And on the side, I still wanted this large pocket watch style balance wheel. Overall, I haven’t sacrificed on any of the pre-assemblies or the technical capabilities in the movement.

14. How did the design of the movement affect the design of the case?

Sylvain Berneron — Once I had done this architecture for the movement, then I had two options and faced a tricky decision. If I had to draw a circle around these components, the movement would become very big and it would also have a lot of empty space on the main plate. The other choice was to use an asymmetric case. To my knowledge, this would be a first, letting the mechanics go free and then design a case to go around them

You find, for example, some shaped movements in a wide range of pieces, for example, Reverso is a shaped movement. But again, the movement has been restricted from the outside by the case shape. You can also take, for example, an HM9 from MB&F (Max Büsser). The movement is completely shaped but it is shaped to fit inside the case, and the case has dictated the shape of the movement. In the case of the Mirage, it’s the exact opposite.

I think the piece that comes the closest to my approach is probably the tourbillons that Greubel Forsey is making, where the case is shaped to house the tourbillon cage, or the globe (in the GMT watches) or even the primary dial. Here we see the architecture of the movement dictating the shape of the case.

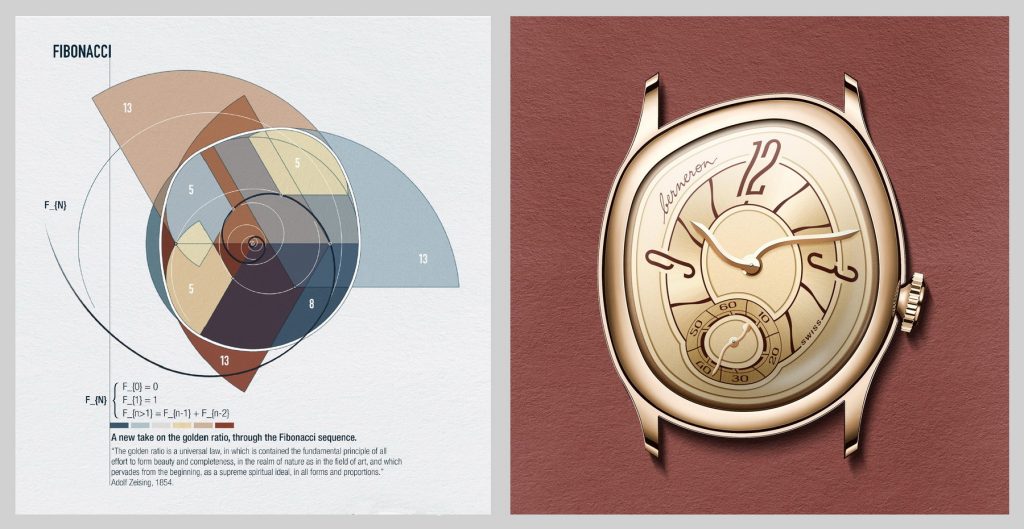

15. In discussing the Mirage, you refer to the Fibonacci Sequence, the golden ratio, seashells and even pine cones. Did you design the movement (and case) to follow these “perfect” natural shapes or was the shape of the movement dictated by your mechanical criterion for the Mirage?

Sylvain Berneron — The design of the Mirage definitely started with the technical requirements of the movement. To me, when you make jewelry, you should not have to choose between style and performance. I was strongly committed to create not only a thin movement, but a movement that would be competent in its task. Otherwise, I would be much better off just doing some sort of a sculpted stone on the wrist, which doesn’t show the time and at least looks very good.

So I definitely started with the construction of the movement. I must admit, I was very uncomfortable at first. I had weeks and months of an extremely uncomfortable procedure of having to deal with the search to find the visual harmony in a space where you have zero points of reference.

And that’s actually the pleasure in doing such a project. It’s an act of love and devotion. It’s the goal. It’s going as far as you can go on the creative map to basically drop a stone on the map where no one has ever walked before. Of course, Rupert Emmerson and Gilbert Albert went very far in the asymmetry, but they completely ignored the technical side of their watches.

More recently, Piaget and Richard Mille and Bulgari went very far with their ultra-thin watches, much further than I went. But they heavily compromised the size and style of their pieces. If you look at the Bulgari Octo Finissimo Ultra, at 1.8 millimeters, it is extremely wide and big, and the ergonomics end up being heavily compromised. The Richard Mille collaboration with Ferrari is 1.75 millimeters, and you can decide whether you like this design.

16. Can you tell us more about your commitment to asymmetry. Does symmetry actually occur in nature (at the visual level, rather than the atomic level) or is symmetry actually a manmade construct that is unnatural?

Sylvain Berneron — I have done a lot of research on this topic, and as a matter of fact, you can actually find both symmetry and asymmetry in nature, whether in plants, in rocks, in minerals, organic living species as well, so both can coexist. But what has always been fascinating to me is, for example, there is no tree that is symmetrical and yet nobody suggests that it would be more beautiful if it had more symmetry.

I’ve read multiple books on the geometry of nature and such subjects, and there is definitely a common mathematical formula that seems to rule the pattern on which natural organisms grow, and that’s the Fibonacci sequence, which can be found in many different types of organisms and structures. When I ended up with my movements being completely asymmetric, this is where I heavily relied on the Fibonacci structures to provide guiding principles that would ensure some sort of visual harmony at the end.

If you don’t follow these sort of principles, you may end up, for example, with something like the Falcone watches, from the 1980s. They took the asymmetry of the case to the extreme, but used a traditional round movement, so to me these watches are more caricature exercises than a cohesive, unified approach for a case and movement.

17. Shaped watches seem to be having a “moment” in 2023. How do you explain the renewed interest in shaped watches?

Sylvain Berneron — If you look in the history of art and fashion and related fields, there is a pendulum movement or cycle. So, you go from left to right in a slower or faster manner, it doesn’t matter. But it always oscillates from one side to the other. I believe, since 2010 until now, we’ve seen the outrageous, unrivaled growth of the steel integrated sports watch. Starting with a couple of leading watches from the 1970s, we’ve had this basic watch in hundreds of forms over the last decade.

It’s funny because the style of this watch is aligned with the car trends of the SUVs. I very actually often refer to these pieces as SUWs (sport utility watches). If you look at a Royal Oak, it is an absolute clone of a big SUV, which is a watch that looks like it can go to Mars when he actually can’t because it’s not a very efficient object as such. Yet, it is a strong status symbol, because it looks powerful.

So, you had these two trends going in parallel, in both the watch industry and the car industry of these SUVs and SUWs. Today, we see how democratized this type of product currently is, with the Tissot PRX being sold on Amazon for $300 and the Christopher Ward Twelve from $1,200.

Two years ago, I thought, “Okay, if we are at the peak in the popularity steel integrated sports watch and cannot go any further, then what is the exact opposite? And is this something where I can find artistry?” It seemed like the right time to reopen the book of the jewelry-inspired approach to watchmaking. And I refer to all the pieces that already existed 50 years ago — in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s — the ultra-thin Piagets with gold cases, dials and hands, and the shaped pieces. These watches can be quite casual or very formal.

I believe that we are seeing it already. You look at the Gen Z of the new collectors coming, the collectors who are younger than me, and may be the tastemakers of tomorrow. They collect vintage Rolex Prince, Rolex Midas, Ultra-thin Piaget, stone dials, gold cases. I have multiple friends that wear their 34 millimeter gold cases, ultra-thin pieces from the seventies and the eighties, ideally with a stone dial, probably on a leather strap. And if this watch is on a metal bracelet, we can expect to see a bracelet that goes a long way aesthetically and is technically demanding, being an extension of the case, rather than an unrelated, technical piece of engineering.

And this is where I think the industry is going. I think it’s a fantastic time for any watch designer to enter the watch industry right now because I think we are at the moment of a significant change and that the pendulum of this type of design is gaining big momentum. We are seeing a big switch in trends, that will gain momentum in a few months or maybe a few years. That will be extremely interesting because, in the next 10 or 20 years, will an Oyster Perpetual or a Submariner or a Nautilus or a Royal Oak still be the watch that people instantly go for? I’m not so sure. What if tomorrow you have a huge shift in momentum and Piaget Altiplano becomes the watch to have?

18. How have suggested that we see the same types of shifts in fine art. Can you explain this.

Sylvain Berneron — In the history of art, when you had the Renaissance, so we went to peak realism, you had painters like da Vinci and Michelangelo, and they could sculpt and paint almost better than a photograph. But once you’ve reached that level where you had this artist who would spend five years to paint a ceiling for god’s sake, these guys were killing themselves, inhaling paint all day for five years to paint a ceiling that would look like the real sky, frankly. But once you’ve accomplished that, of course the next step is to go abstract because you have no other choice.

This is what brought us impressionism and cubism and similar developments, because they were thinking, “Okay, we’ve been there, we’ve done that. We know what realism is. It is much more interesting to go the other way around.” Consider Picasso, for example. Very few people know that when he was a teenager, PIcasso could paint tremendously well in a realistic style. He painted “Science and Charity”, at age 15. A lot of people think the guy was drawing like a kid because that’s all he could do. Picasso said that when he was a kid, it took him five years to be able to paint like Raphael or to copy the masterpieces, but it took him his entire life to relearn how to draw like a kid.

Turning back to watches, after 50 years of the steel integrated sports watch, what more can we expect from the inspiration of the Royal Oak or the Nautilus? Perhaps this style has been fully-developed, on the one side, and fully-democratized, on the other side.

Maybe it’s time for us to start drawing like kids!

19. A few days ago, Cam Wolf, writing in GQ, suggested that the Cartier Crash is the “lazy comparison” for the Mirage, but in fact there seem to be many people who when they first see the Mirage, they suggest that it looks something like the Crash. Can you comment on the Crash and also tell us about the designers who have inspired your work, in the watch industry and in other realms?

Sylvain Berneron — First, I should say that it’s funny that people so often refer to the Cartier Crash. I think a lot of people feel the need to compare the Mirage to something, so perhaps the Crash comes to mind. Still, if you take the Crash point by point, except for the fact that it is asymmetric, I do not recall a single common point with the Crash. You take each element — the case, the dial, the hands, the movements, the strap — everything is different between the Crash and the Mirage, point by point. Yet at the end of the day, people seem to make the Mirage land into the same corner of the market, which I understand because these are asymmetrical pieces.

Coming back to the types of watches that have inspired me, I start with classic watchmaking from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. We see this represented in brands such as Patek Philippe, Breguet, Lange and Vacheron Constantin.

After this, I consider the shaped pieces that we started seeing in the 1960s, and major sources of inspiration are Gilbert Albert and Rupert Emmerson.

Albert initially worked in the 1960s, mainly for Patek Philippe, using asymmetry and drawing inspiration from irregular shapes in nature.

Rupert Emmerson worked for Cartier in the 1960s, and he designed the Crash as he sought to draw a watch that would be entirely different from all the others.

Albert and Emmerson did a great work in terms of aesthetics, although they (or perhaps their brands) always seem to have neglected the technical and the movement side of things. You can see that their beautiful watches incorporated very simple, unattractive movement.

This is an area in which I like to believe the Mirage is taking things much further, really, really much further. The Mirage movement is itself a piece of art and will also perform very well.

I should also mention that Eric Giroud has been a great inspiration for me. He has shown tremendous versatility over his career, with his work for MB&F representing a unique contribution to current watch design. Time will tell who will succeed to Eric for the decades to come.

Looking beyond watches, I also mention architects such as Gaudi, for example. Or you have a lot of, even the Dadaism, if you take Marcel Duchamp for example, he took a great pleasure in disrupting the stiff order of art in its time. And I try to do the same in my field of discipline by making projects that really venture into something we haven’t tried yet. And to my knowledge, letting the mechanics free of every restriction is a new approach to making a movement.

20. Turning to the specifics of the Mirage, can you explain why you are using gold not only for the case, but also much of the movement and even the springbars? Was this an artistic decision or a technical decision?

Sylvain Berneron — There are two reasons why I choose to make a full gold construction. The first reason is the longevity of gold. There is a good reason why goldsmiths have been using gold for centuries. It’s because it is corrosion-free and you can refurbish it endlessly with the minimum amount of trouble. When I designed the Mirage, even in the surfaces I chose and the placement of the finishings, it was extremely important for me that, even after 50 or 100 years, a good goldsmith could re-weld a lug, re-brush the side of the case, re-polish a bezel, whatever it may be. I used common alloys, so 18 carat gold, to make sure that this piece could stand the test of time.

Another trend in the industry – which I am very sad to see — a lot of pieces that are being hyped and pushed and bought by collectors, and they probably do not understand fully what they are buying. For example, If you buy a frosted Royal Oak in gold, once the bracelet or the case is scratched, there is no way that you can refurbish the frosted surfaces back to their original state. The same applies to ceramic cases and to composite cases, such as those that Richard Mille is using. UV light degrades composite materials, so you will never see a composite case that has been worn in the wild for a hundred years and kept its structural integrity, because it is not physically possible.

The second factor leading me to use gold for the Mirage is the fact that one goal of the Mirage is to have a highly contrasted product. The Mirage is very thin, but I want to have the contrast in the feel on the wrist as well. Again, I am going in the opposite direction of the steel-integrated sports watch, which often looks very large but is very light. I want a very thin watch that will be heavy on the wrist. So the best way to do that is to build everything in gold, even the movement.

21. Can you tell us about your effort to keep the Mirage so thin. Why is thinness on the wrist an objective for you?

Sylvain Berneron — To me, thinness is a form of complication. And as a designer, thinness in the movement is the most beautiful, romantic, noble form of complication.

Also, we live in a world where wealth disparities are increasing and the times where you can walk around in a city with a massive gold Submariner on your wrist with a pair of sunglasses are over. It’s the same for the bright orange Lamborghini with scissor doors. I don’t think this is the way forward. I think that the future of luxury will be much more low-key and much more private. Perhaps the biggest downside of the Mirage is that it is a very “if you know, you know” type of product.

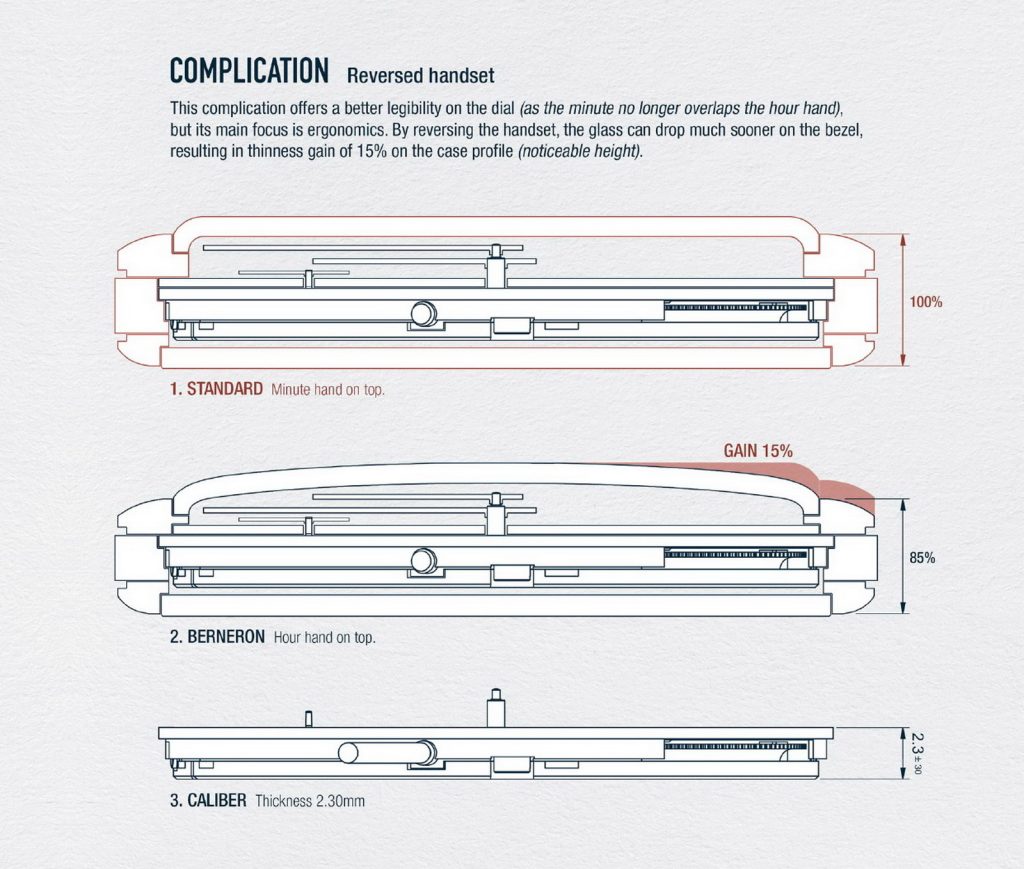

Notice that the movement carries an inverted handset, which means the hour hand is on top of the minute hand. The entire goal of this complication is to reduce the thickness of the case by 15% because you have the shorter hour hand on top, and that allows me to drop the profile of the glass much sooner onto the bezel, unlike any other watch. And it’s funny because if you look at the Chronomètre Antimagnétique made by Rexhep Rexhepi for this year’s Only Watch, you will see that his minute-hand is actually stepped down in order to basically pursue the same objective. So it’s the same problem, solved in two different ways.

22. Let’s talk about some components of the Mirage. While I understand that these elements create a unified whole, can you comment specifically on the typeface, the shape of the sector markings and the shape of the hands?

Sylvain Berneron — So the entire watch has the same “parti pris”, which I would call its creative direction. I would summarize this as my love of very traditional things on one hand, combined with creativity and exploring on the other hand.

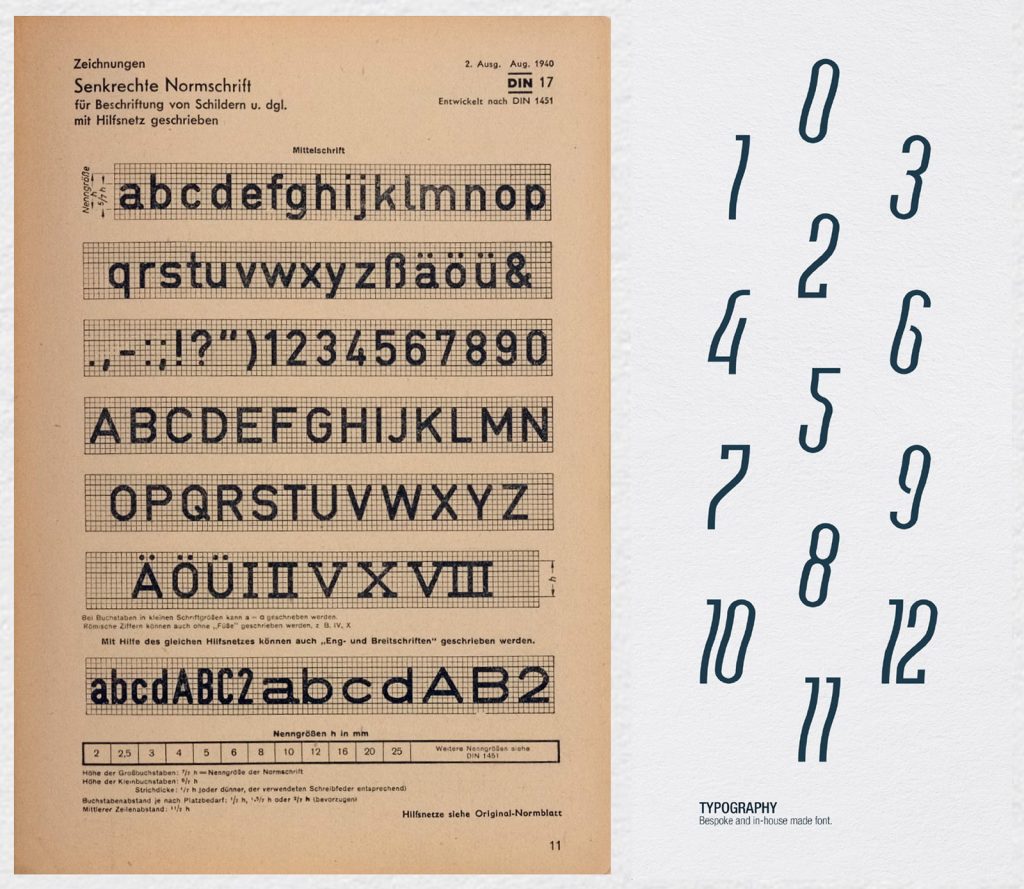

The typeface is inspired by a very well known font called “DIN” (which means “Deutsches Institut für Normung” [German Institute for Standardization]), which was developed in the early 1930s.

The DIN typeface has been widely used in industry and transportation in Germany. I discovered it during my time at BMW because it was written everywhere. One interesting characteristic of DIN is the fact that each letter or number occupies the same space, unlike a normal font where, for example, the W or the M is much wider than the other letters. So in very German typical manner the typeface uses the same area for each letter. So this is the reason why in the typography of the Mirage you do not find a single straight line. It’s all a mix of curves and counter-curves together, in order to create a new font. This typeface also reflects the philosophy of the project, in the sense that it reflects that willingness to do a sidestep compared to the normal way and to venture into untouched territory.

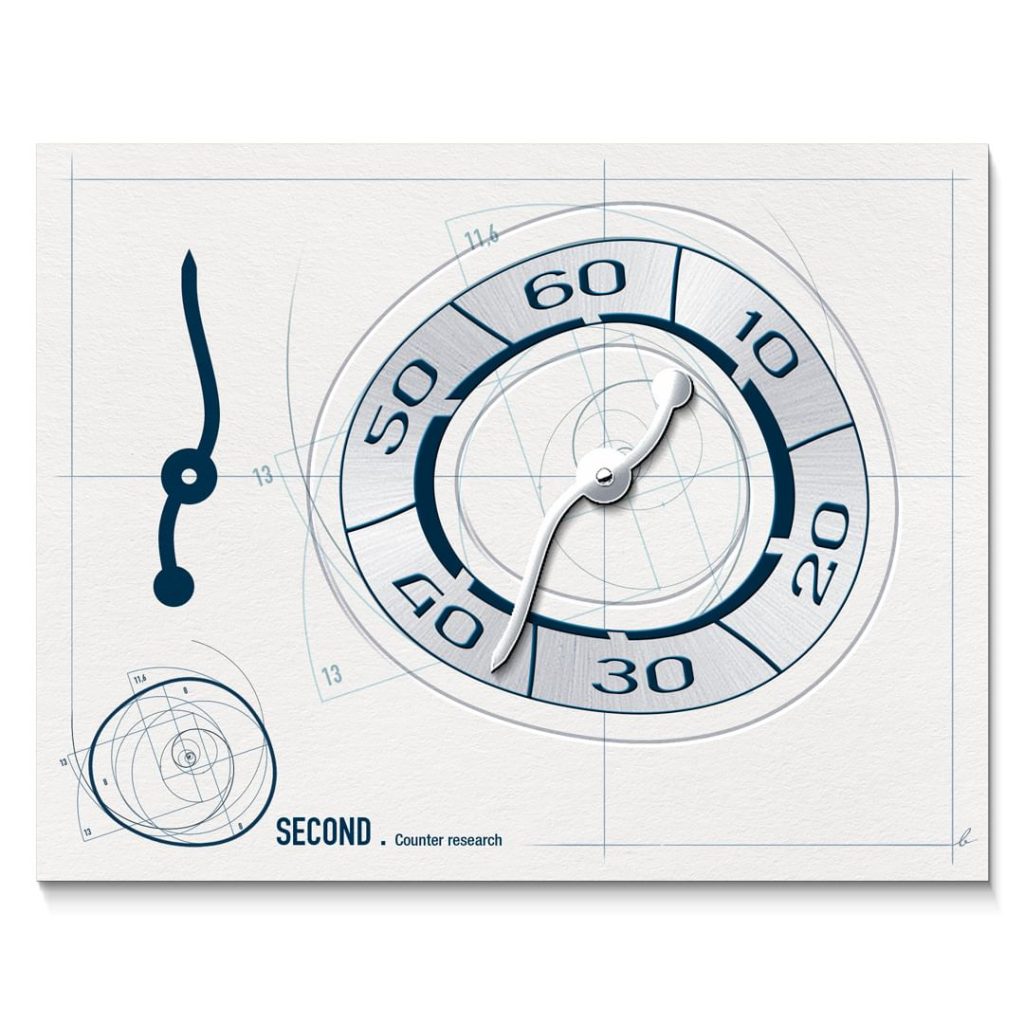

The same goes for the sector dial. I’m in love with this very traditional approach, as the purpose of the sector markings is to maximize the legibility of the dial. So invariably the sector markings are straight and stiff. But in my case, because I wanted to break the rules, so to speak, I took a great pleasure in starting with these very straight, traditional elements — such as sector dial and the DIN font — and twisting them into something else. No one says that you could not do a twisted sector dial.

Regarding the hands, the Crash shows what we might call a “problem”, but there was an elegant solution. With the Crash, there are some times of the day when the hands do not point the right number, because everything on the dial is so twisted and the hands are yet straight. So because I had a twisted dial, I wanted to twist the hands as well, to make sure that it would all become a coherent form of language at the end. And the hands are always in the correct position, pointing precisely to the time.

23. Throughout our conversation, you’ve referred to several tensions and conflicts — the movement vs. the case, performance vs. style, thinness vs. weight, symmetry vs. asymmetry, etc. One friend described “sleepless nights” thinking about this watch. Are such tensions inherent in the design of wristwatches or do the tensions occur only only when you’re going outside the traditional boundaries to mark a new place on the map?

Sylvain Berneron — So I think in a good object, a good design object, I think there has to be some tension. Let’s take a counter example, if you let the function dictate everything, you end up with a pure tool. So for example, a hammer is an object that has no tension because by definition, the only factor that has been taken into consideration is the function of the tool. Nobody cares about how good a hammer looks.

The opposite example would be an object where the looks are paramount, might be a wedding dress from Christian Dior. It looks absolutely amazing, but you cannot walk five meters with it without tearing it apart, and you probably can’t really breathe in it and you will not be comfortable dancing in it. To me, as an industrial designer, this is a failure, because this dress does not function well, even at the wedding.

This is how I see it. To me, the best objects are the ones that can marry technique and art together. And when you can combine art and technique together, you end up with these objects that last for centuries, but — yes — there will be some tension in finding the right balance.

24. So where do we find this marriage that gives us peace and harmony? Putting aside the Mirage, is there one watch that you can look at and say, “This is harmony, this is perfect?”

Sylvain Berneron — In my opinion, the Lamborghini Miura is a great example of what art and technique can do together. We can also mention, for example, a Patek 96, the early ones from the 1920s and 1930s. Amazing watches, very harmonious in my opinion, but I should say that the level of complexity on the movement and on the case is rather simple. Everything is very well-executed, but yes, there is some tension there, but at a very acceptable level.

Then when you venture into the Mirage type of complexity when you pull gold into the movement. Because a Patek 96, you have a gold case, fine, probably gold hands, gold-applied indices, but the dial is still brass, the movement is brass, the movement is round. So it is still a very rational object made in a very cautious industrial process.

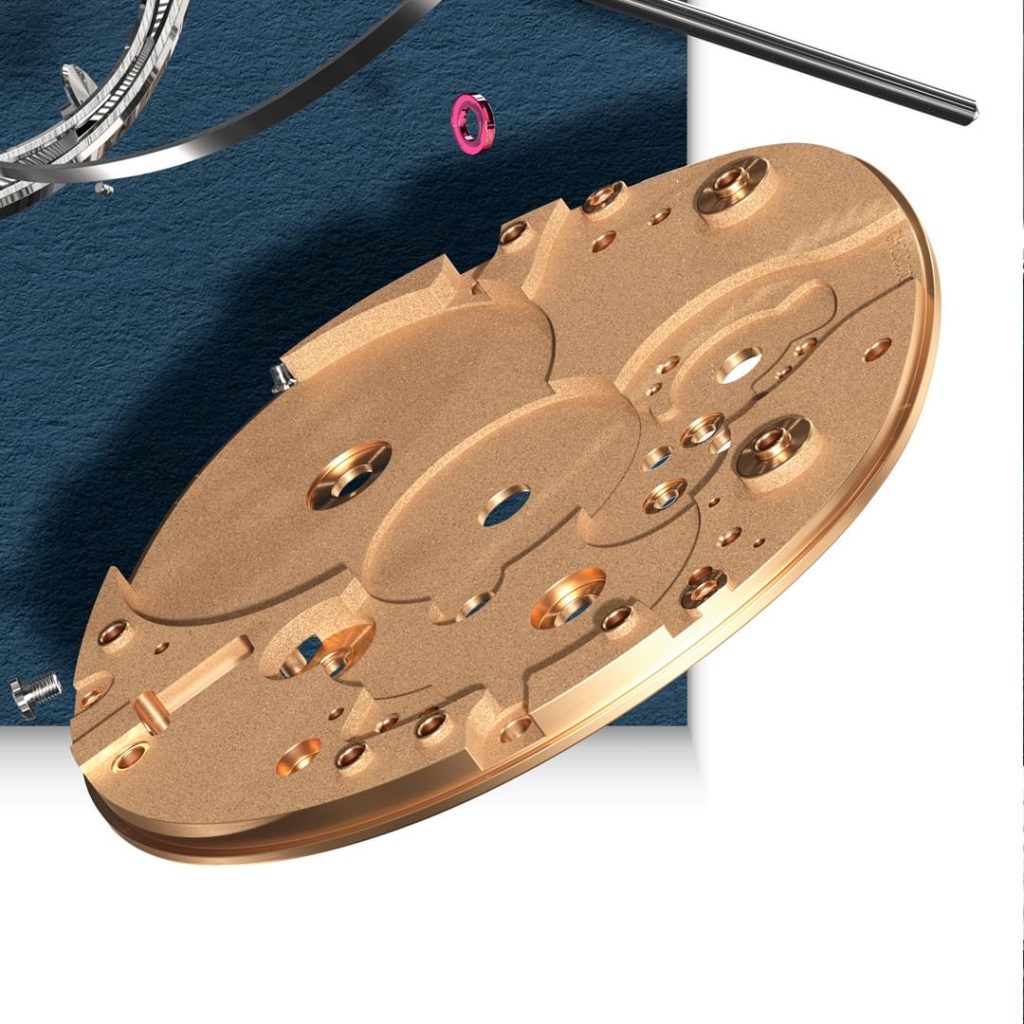

Once you start breaking these boundaries, you end up in the Mirage territory where the movement is not only a movement, it is also a display of finishing, of craftsmanship using gold. So the movement of the Mirage could itself be a jewelry object. It could be an animated jewelry sculpture, so to speak, because it is made of gold and the pieces are manipulated by very skillful craftsmen and watchmakers. Then people who decorate the movement with anglage, people who do the guilloché, all these things.

And same goes for the case. The case is also a work of jewelry because it is made of gold, it is very thin. It requires immense dexterity to apply the finishing on it while being a great challenge of technique, because putting together such a thin case — and mine is water-resistant unlike, for example, the Patek 96– this is where you land in a territory where the lines start to blend between art and technique. One is the other and vice versa. And this is really what moves me.

Making the Mirage

25. You’ve identified Le Cercle de Horlogers as your movement maker. Can you comment on other suppliers. For example, who will make the cases, the dials, the hands, etc.?

Sylvain Berneron — In the watch business, identifying suppliers can be very difficult. Some of my suppliers would face pressure from their other customers if I were to identify the supplier. This is one part of the industry that very few people know, but it happens very often that when a brand or a project gets a lot of traction, some others try to pull some cards and try to make phone calls to stop it rather than working on their own watches.

When it comes to Le Cercle de Horlogers, I can publicly say they produce and assemble the movement for me without having to fear any bad consequences. But this is not the case for every supplier, which is why you will never hear me publicly saying who I work with for the case, the hands and all these things

But without mentioning the name, I can say that the hand maker is the same company that make the hands for Greubel Forsey, for example. The casemaker is making all the minute repeaters for Vacheron Constantin, which require a lot of hand adjusting and then extremely precise tolerances so that these pieces could open and close and have the right sound and everything. The dial maker is also doing work for a leading brand in the industry.

I am comfortable that my suppliers are the best of the best.

26. Can you tell us who will take these wonderful components and actually assemble the watches? Will this be handled by your employees or will it be outsourced?

Sylvain Berneron — So for the first years, the Mirage will be assembled at Le Cercle de Horlogers, because the movement is the most complex and fragile component of them all, and therefore it has to lead the rest. This is why, for example, I have asked the casemaker and the dial maker before they produce anything to have a validation from Le Cercle de Horlogers to make sure that their components would meet their requirements.

Le Cercle de Horlogers has at least 25 watchmakers and, among them, five are called “master watchmakers”. They work on tourbillons and minute repeaters. Because the Mirage is a full gold construction piece, it requires extreme attention while being assembled because you do not want to damage the dial, the hand, or whatever component because these are gold components, and if any need to be replaced it is much more costly than the standard brass hand or brass bridge.

27. Can you tell us about the milestones for the Mirage. When will you have the first working prototype, when will the first watch be delivered and what about the 48th piece?

Sylvain Berneron — We plan to assemble the first movement right before Christmas. And before Christmas we will do what is called the qualification of the movements. We’re going to assemble it, test it, and do what we call the “phase homologation,” having the movement run extensively for a period of time to check how it keeps chronometry and to be certain that nothing breaks down. It’s in order to qualify the movement for its quality and its chronometry. So this will be done at the end of 2023.

Then the production is already going on in parallel and we have some components which we call “semi-finis”, so they are half finished. Which means at the moment I am producing half components that are simply half finished. And once the qualification is approved, then they can finish each component to its final level of finishing. And that is to ensure that we do not produce any parts that would not pass qualification.

We are going to ship the first 24 pieces in the second quarter of 2024, so that’s April, May and June. Then the summer is usually quite slowly in Switzerland, as you know. We will then ship the second 24 pieces in the fourth quarter of 2024, so October, November, December. And then as of 2025, we will begin shipping 24 pieces per year.

28. So at the end of 2024, one year from now, you still won’t have employees. It’s you and Marie-Alix, your wife, employed by Berneron and everything else is outsourced. Is that correct?

Sylvain Berneron — Yes. At this stage, that will be the case. I want to be extremely conservative when it comes to growing the company for one reason. I have seen many companies that started like a rocket going to the moon, having fancy offices and champagne and zillion of staff just because they sold a couple of years of production. And down the line, I’ve been in the industry long enough to know that the hype comes and goes. And even the difficult periods in the market come and go.

It is essential for our company to be resilient. So I will always make sure that we have enough resources to sustain any downturn and some money to run some offices and to hire people that we have enough resources on the backside to make sure that we can sustain it in the long run.

So I will, just like I do for the watches, grow it very slowly. Very, very slowly. The goal in 10 years is to have a team of 10 or 15 people. Which means I will probably, in the first two years, stay with two people — which means Marie-Alix and I — before we start hiring maybe a couple of people and get a small office.

As we have discussed, we are developing a watch that is very risky, but I am happy to take risks relating to the product. I must avoid additional risks relating to the company, such as employees and offices. I must always have some buffer, because at some point something will go wrong. No doubt about it. So when this will happen, I want to make sure that we have the cash and the resources to not kill the company.

The Moment

29. You introduced the Mirage during the first week of October, after 10 months of whispers and hints. How has the Mirage been received? You stated a long time ago that you were expecting a polarizing watch — some will love it, some will hate it. What have you seen through the first month that the Mirage has been public?

Sylvain Berneron — So I haven’t had the time to completely grasp the entire feedback, because my mailbox is full as we speak and I haven’t had the time to dive in it. But overall feedback has been extremely positive.

I’m also very touched to see that the vast majority of people see the commitment that we made to the Mirage. I must admit I’m very touched because I was mentally ready to go to war and cross the desert with bare feet, because that’s also something that my mother taught me, and it’s the hardest part to learn as an artist. If I like the watch enough, this is where the value in the work will be. I’ve been extremely stubborn about this project and not letting any influence or drawbacks slow me down.

We have had tremendous feedback over the last month. We’ve allocated all 72 of the Mirages to be produced in the first three years (by the end of 2025). So the next step is the year-four watches, with delivery by mid-2026.

I thought that I would have to go to war, but it’s the polar opposite. For example, I’ve been personally congratulated by the designer Eric Giroud, by Max Buseer, by Emmanuel Gueit. I received personal congratulations from these guys. And to me as a designer, that means a ton. I also have the privilege to count among the first clients guys like Roni Madhvani, Auro Montenari, Laurent Picciotto and Fred Mandelbaum. These are highly esteemed and educated collectors, and to me this is more than enough.

Laughing the other day, I told my wife, “I can die now.” If I can touch these guys, who are the most discerning collectors, I think it’s a big compliment for me. I don’t need to please the crowd of people.

30. How would you describe the criticism that the Mirage has drawn?

Sylvain Berneron — Thank God I also have people that completely hate this product and that express it loudly, and I’m very pleased that they do because, as I said, the Mirage is a very “if you know, you know” type of product. People who hate the Mirage are the ones that are looking for a status symbol or that are looking for a product where all the money is put on the outside. These guys, they absolutely hate the Mirage because it’s too small, it’s too expensive, and it doesn’t punch hard enough in the face of others. So of course they go and criticize, and I fully understand. I am very happy to have some haters. With this kind of design, the worst response for me would’ve been indifference on both ends. For example, if people were to say, “Yeah, why not? Cool.” And nothing happens.

31. Has the tremendous reception to the Mirage over the last month changed anything in your plans for the brand, plans for your life, etc.? Has this response changed the way you think about the future of your brand and even your career?

Sylvain Berneron — So at the moment, I try to stay very stoic because my main priority is to deliver the first 24 pieces over the next six months and to have happy collectors and Mirage owners. Until that is accomplished, I must focus only on the current tasks. But nonetheless, I must admit that this project seems to be going better than I could ever have imagined.

As I mentioned, I was ready to cross the desert with naked fucking feet for two years, and I would’ve done it because I consider this watch good enough so that I can show it to people and even defend it. But I also know that I cannot control the outcome and this is where I have to be brave. Of course, it is better to receive the hugs than to have to go into battle, so this helps our frame of mind as we address the current tasks.

All this goes to show that when someone truly puts love and devotion into something, I’d like to believe that others feel it. I even had collectors who told me that they would never buy the Mirage because it’s not for them, but they thanked me dearly for having the courage and the energy to undertake this project.

32. Tell us about your 10-year plan for the Mirage. You will produce 24 watches per year for 10 years, half the Sienna and half the Prussian Blue. Will there be additional colorways or materials over the 10 years? What will we see?

Sylvain Berneron — I have a very intuitive approach to this. As a designer, as an individual, I think overall the human race right now, we produce too many things, too fast, of the same shit over and over again. And it’s like when your body develops a resistance. For example, if you take painkillers — you take one gram today, then you can take five. And you will develop a resistance, so at the end you will have to take ten grams to have the same effect.

Fifteen years ago, when I started work as a designer, we could follow the new product introductions across the fields of fashion, architecture, cars, watches, etc., by looking around some good websites for a couple of hours per week. Currently, even if I were spend all my time looking around, I could not follow all the products that are being launched. So the brands struggle to get attention, because in a week when 20 watches have been launched and they are all round, all in titanium, all integrated with a bracelet, and all with the latest color of the moment, why should people care?

So I’m making a huge and risky bet that we can take a different path. We will produce very little, to the best of our abilities, in a stable manner, so that people do not have to rush to the store to get one because they are worried that they will miss out or the watch will look different next year. Brands create hype to get customers to buy their watches quickly, but my approach is different. For the next 10 years, I will produce only 24 watches per year, 12 in the yellow gold and 12 in the white gold. And there is no rush to get one. You can wait and see.

33. On your Berneron website, we see information about the Mirage, but there are references to the brands “Collections” and a “Work in Progress” for 2026. Can you give us any hints about the models that will come after the Mirage?

Sylvain Berneron — So the goal for Berneron, over the long-term, is to develop five entirely bespoke calibers. So I’d like them to grow into complexity. I’d like to venture into a dual time, a jumping hour, a complete (or perpetual calendar), and maybe a tourbillon. I have ideas for these next four complications on my sketch pad.

With the Mirage, I have laid down the basis of the DNA for the Berneron brand. So the golden rule for me is to bring something new onto the table. When I started Berneron, I asked myself, “Okay, I am coming five centuries after the first clock, more than a century after the first wristwatch. If I show up with yet another watch brand, which these days they seem to grow more than mushrooms, why should people care? And why should it stay relevant in the long run?”

My mission as a designer, and as an artist, is to really drop some stones in the corners of the map where people haven’t been yet. And I like to believe that the Mirage does that, and I will want the other collections to do that, as well.

34. Over the long term, what position will Berneron hope to occupy in the watch industry?

Sylvain Berneron — I believe that Berneron will have a unique position that is relevant to the industry. If I would describe the Mirage to you while we ride an elevator, I would say, “Oh, Jeff, I’m working on this watch. It’s a time only watch with a small second at six o’clock. It has a sector dial. It’s a gold case with a manual wind movement on a leather strap.” All these things are true, and you could very well visualize the Patek 96 sector dial from the 1930s or many other traditional watches. And yet when you open your eyes, and I show you the Mirage, it’s a completely different take on the most traditional type of watch. I take the most conservative, restrained elements, and twist them to offer an entirely new look.

Here’s what I have done. If I had opened a restaurant, for example, my first meal would be a cheeseburger. And yet my goal is to come up with my own very special, unique proposal of what a cheeseburger should be. To me, that’s the most noble exercise as a watch designer and probably as an artist or a cook. You take the most common thing and you try to give it a different flavor. If I’ve gone far enough — time will tell — then I believe the Mirage will hold its place as a piece that will be remembered. I think all generations of designers would like to bring something new to the table, a new approach to show that things can be done differently. So this is why I’ve done this project.

35. Let’s go back to our elevator. We’re on the elevator again and have exactly one minute to chat about the Mirage. On the ride up, you gave me the generic description of the Mirage. Now we’re on the elevator again, riding down, and you want to give me a more specific description of the distinctive features of watch. How would you do this, in one minute?

Sylvain Berneron — Here is my one-minute description of what we have done. We have created a new watch and we freed the movement and as a result, also its package, the case. So you have to imagine a watch that is almost moving on your wrist, because the mechanics were set free. So the movement shaped itself according to its needs. So it’s a very organic approach. The case is all gold and has been built to the highest standard of jewelry making, shaped freely to house this movement. You will end up wearing a painting on your wrist, something that is almost in perpetual motion, but ever so slightly, so that it’s not crazy.. I hope that the Mirage will have a tremendous magnetism, once on the wrist. That’s what I’ve been trying to do.

36. When I first asked our friend, Fred Mandelbaum, to describe how the Mirage looks on his wrist, he said that the Mirage is “mesmerizing.” What is your one-word description of the Mirage?

Sylvain Berneron — The first word that comes to mind for me is “de-restricted” watchmaking. This is a watch that was made without restrictions and without compromises. We can think of a movement and a case, and individual components, that have all broken free of the usual rules and restrictions. The Mirage seems to be even more appreciated by experienced collectors because they have the time to consume watchmaking for so long, and then all of a sudden a Mirage becomes very refreshing. It sits in its own in a little corner. It’s like tasting a wine that is outside of the traditional varieties; this is an entirely new variety that has not existed previously, and which I believe connoisseurs will enjoy.

The Berneron Mirage — Specifications

Functions: Hours, minutes and small seconds

Movement: Manual winding; 60 hours of power reserve; 21,600 vph (3 Hz); 30.0 mm length x 28 mm width x 2.30 mm height; 135 components; 17 jewels

Movement Materials: 18 karat gold main plate, anchor bridge, minute bridge, escape bridge, barrel bridge and second bridge; stainless steel balance bridge and winding gears

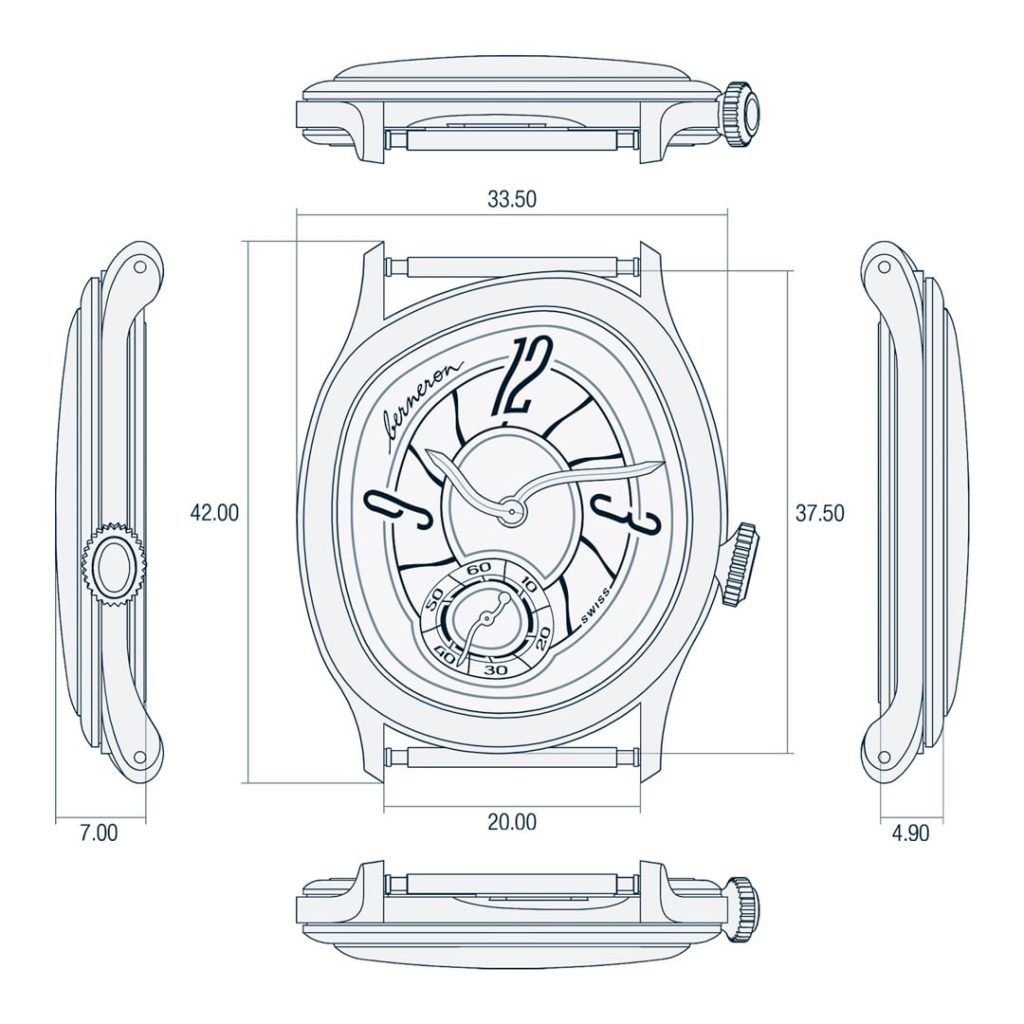

Case: 18k yellow gold (Sienna) or white gold (Prussian Blue); 37.5 mm length x 33.5 mm width x 7mm height, water-resistant to 30 meters; 20.0 mm between the lugs

Dial: 18 karat gold; satin-brushed and polished

Hands: 18 karat gold, polished

Strap: Traditional straight-cut grained calf leather (top & bottom) with tone-on-tone stitching

Price: 2024 – CHF 49,500; 2025 – CHF 55,000

Additional Information — See the Berneron website and Instagram.

Thanks

Thanks to Sylvain Berneron for being generous with his time in discussing the Mirage and the Berneron brand.

Thanks to my two Atlanta editors (and one in Vienna) for the excellent suggestions all along the way, and especially for allowing me to convince them that it would be OK to publish a 10,795-word interview.

Thanks to Roni Madhvani for supplying some of the photos used in this posting. Follow Roni on Instagram.

Jeff Stein

November 12, 2023