Today, at Watches and Wonders in Geneva, Switzerland, TAG Heuer has introduced its new “Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph”. Over the period from circa 1890 into the 1970s, Heuer produced many different types of split-second mechanical chronographs, but all of them were “pocket chronographs”. Today’s new Monaco is the first mechanical split-second chronograph that TAG Heuer has made in the form of a wristwatch.

In this posting, we will describe the key features of the Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph, and also put this new chronograph into the context of TAG Heuer’s history of producing the very best chronographs and other timepieces for racing, rallying and other sports. This new Monaco chronograph embodies TAG Heuer’s deep heritage in motorsports and precision timing, while incorporating the latest developments in materials and watchmaking techniques.

After 164 Years, TAG Heuer is Making a Split-Second Chronograph for the Wrist

For the past 160 years, TAG Heuer has been the leading Swiss brand in offering a comprehensive catalog of stopwatches, chronographs and other timing equipment, with a particular focus on timing for motorsports and track and field. TAG Heuer has been the official timekeeper of the Indianapolis 500, the Olympic Games and Formula 1, and also of the Ferrari, McLaren and Red Bull Formula 1 teams. And speaking of Heuer stopwatches, let’s not forget that John Glenn wore a Heuer stopwatch on his wrist during his Mercury flight in February 1962 and NASA used one to time the landing of The Eagle on the surface of the moon in July 1969.

Heuer has lived in the world of chronographs, and in this world the split-second complication (also called “rattrapante”) is viewed as representing the highest form of watchmaking skill. For chronographs, the split-second feature is described as being the “queen of complications.” Assembling and adjusting a rattrapante chronograph is a difficult challenge for the watchmaker, but the timepieces are exceptionally useful for many types of timing. .

Heuer will produce 40 of these Monaco split-second chronographs per year, half of them in black-coated titanium cases (with red accents on the dial) and half of them in uncoated titanium cases (with blue accents). The movement of the new Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph is produced by Vaucher Manufacture Fleurier (which we will simply call, “Vaucher”), with various enhancements made at the direction of TAG Heuer. These chronographs will have a base price of $138,000, with the customer being able to specify various types of customization, which could bring the price up to $169,000.

Rattrapante – The Queen of Complications

In simplest terms, split second stopwatches and chronographs have two second hands for the stopwatch. They normally rotate together, with the split-second hand on top of the primary hand, so at a glance they appear to be a single hand. The user is able to press a pusher to stop the split-second hand, while the primary hand will continue to travel around the dial.

When the split-second pusher is pressed a second time, the stopped hand will instantly rejoin the moving hand, as they continue around the dial. (It is this “catching up” with the primary hand that gives us the name “rattrapante”.) By pressing the usual chronograph pusher, both the minute hand and the two second hands can be stopped.

With the ability to stop the two second hands independently of each other, the user can measure the elapsed time of two different events. In motorsports, for example, the rattrapante can be used to time two laps of a race, to measure the time differential between two racers, or to determine the difference between the time of a driver’s arrival at a rally checkpoint and the time specified in the rally instructions. Split second timers are also useful for scientific and industrial applications, for example, in time / motion studies.

The split-second chronograph complication is considered one of the three highest achievements among “complicated” watches, with the other two being the perpetual calendar and the minute repeater. Over the period from approximately 1890 through 1975, Heuer offered a range of split-second pocket chronographs, all of them powered by mechanical movements. These timepieces were the most complicated timepieces in the Heuer catalog, and also the most expensive.

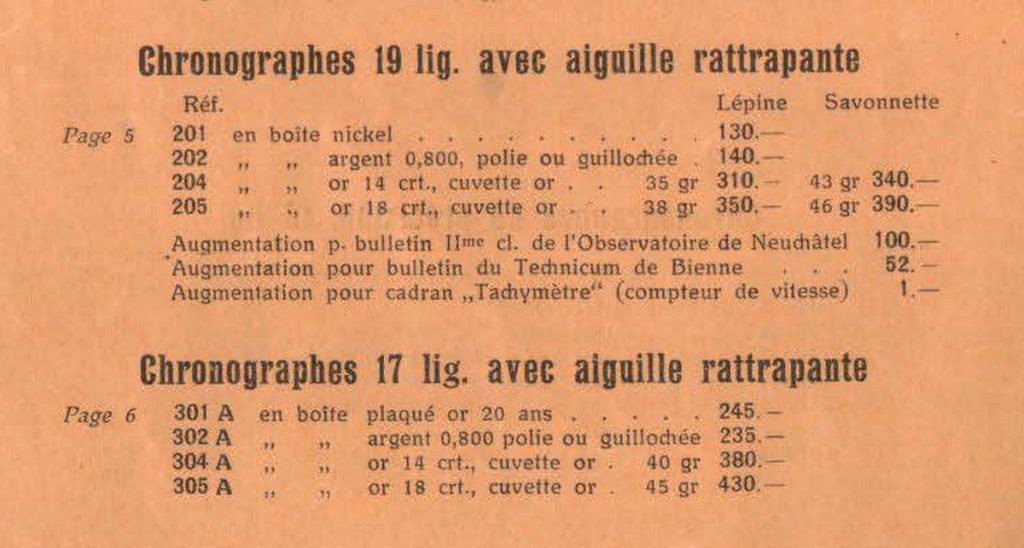

For example, as shown in the price list above, in 1930 the least expensive split second chronograph cost 130 Swiss Francs, while a simple pocket chronograph cost 40 to 50 Swiss Francs and a split second stopwatch cost just over 50 Swiss Francs. Similarly, in the 1975, we see Heuer’s pocket split-second chronograph (Reference 11.402) selling for 640 Swiss Francs, while the Autavia (Reference 1163) was priced at 225 Swiss Francs. These are complicated chronographs that require many parts, and considerable skill to assemble and adjust.

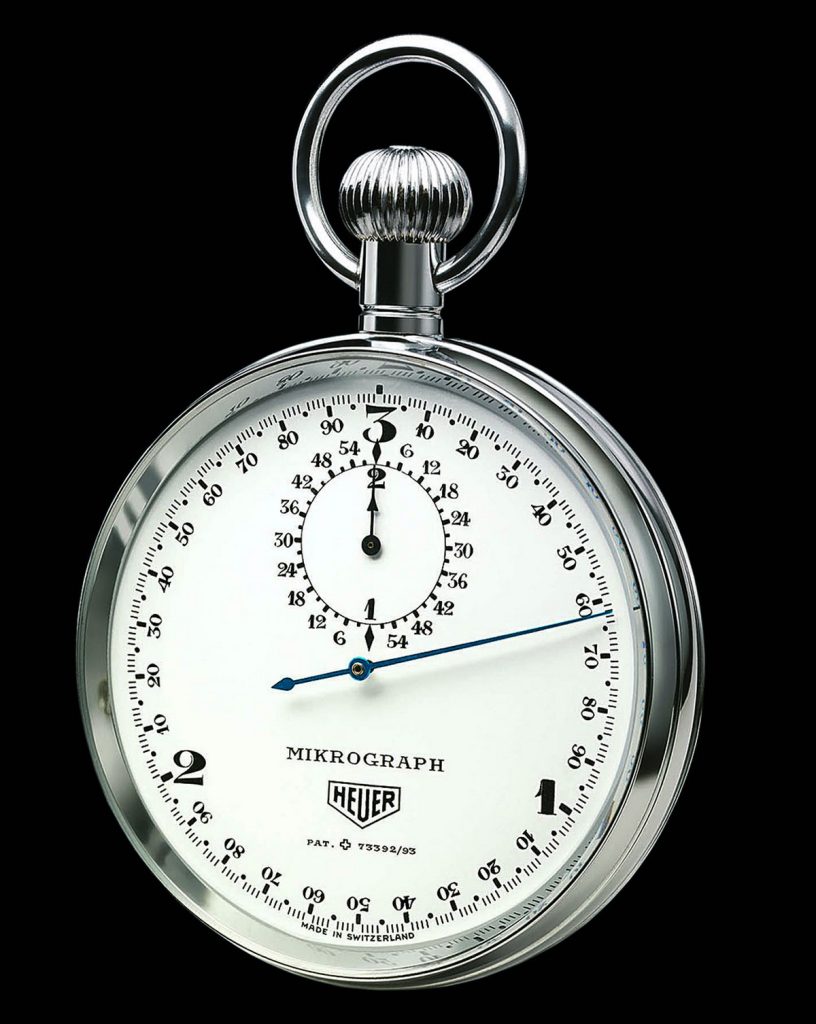

We look at Heuer’s catalogs over the decades, and wonder why the company never made a split second chronograph for the wrist. Nick Biebuyck, Heritage Director at TAG Heuer, offers this response, “Heuer always sought to produce the most functional types of timepieces and the type of precision timekeeping that was required for racing, rallying and other sports required the larger dial of a pocket chronograph, rather than the smaller dial of a wristwatch. When you compare the “display” that is possible with a 36 or even 40 millimeter wristwatch to what you get with a 52, 57 or even 65 millimeter pocket timer, there is an enormous difference. For reading 1/5 or 1/10s of seconds, or even full seconds, you need the larger display of the pocket timepiece.”

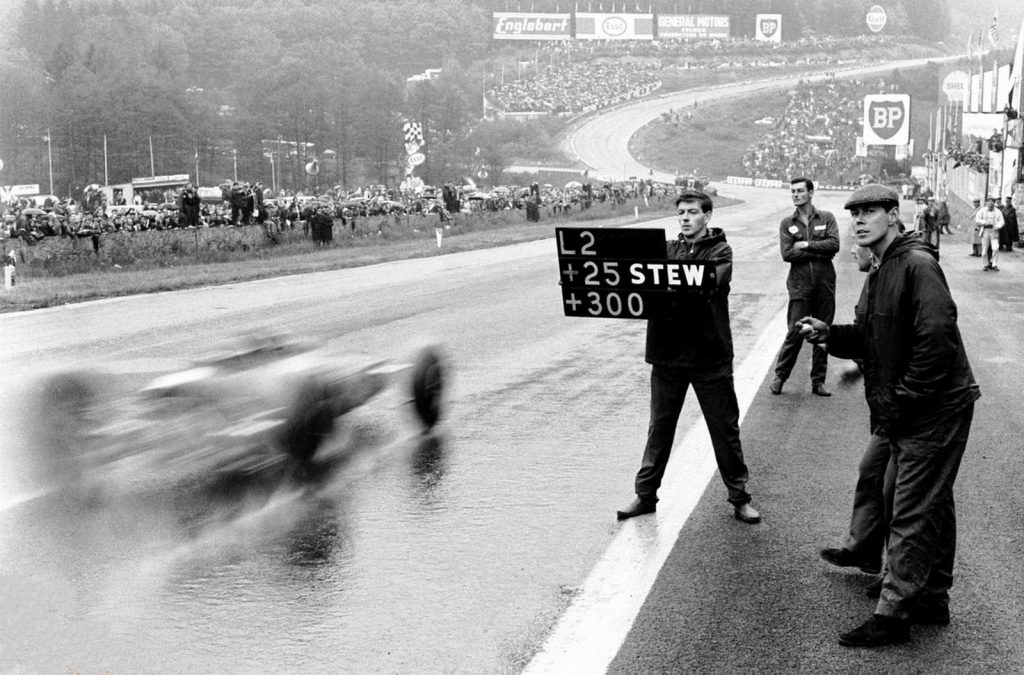

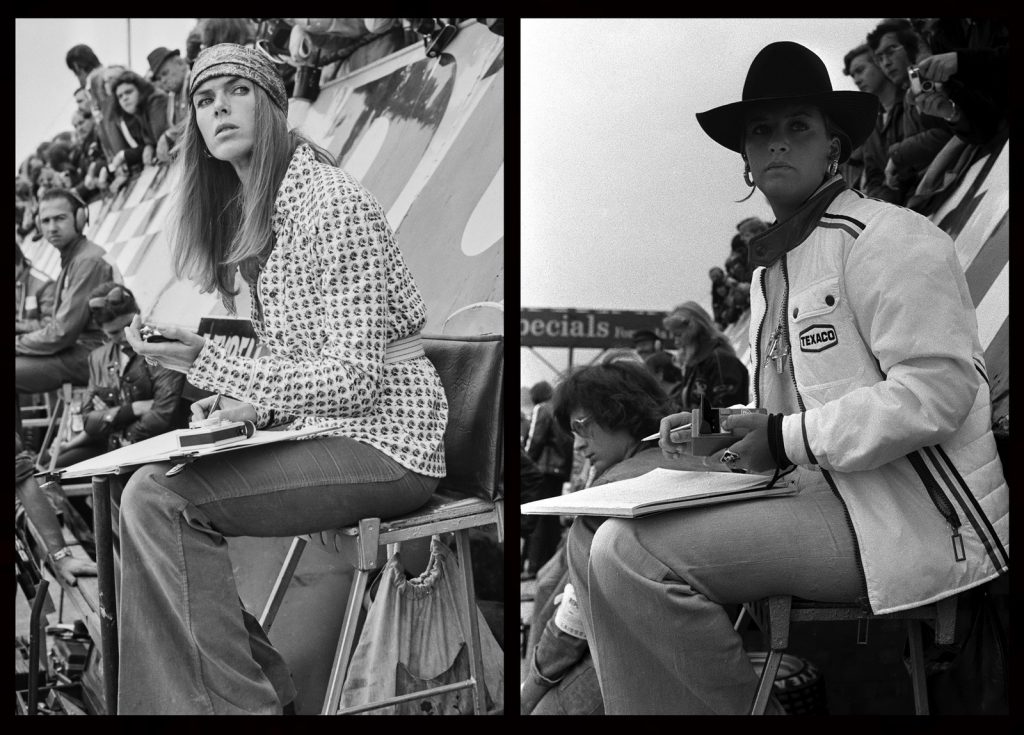

We think back through images of teams timing their cars at racetracks, and the tool of choice was always the handheld stopwatch or chronograph. Wristwatches were nice for style, but precision timekeeping required the larger timepiece. Consider the additional precision and legibility that the 52 to 57 millimeter pocket chronograph can deliver, compared with a wrist chronograph in the usual 36 to 38 mm range.

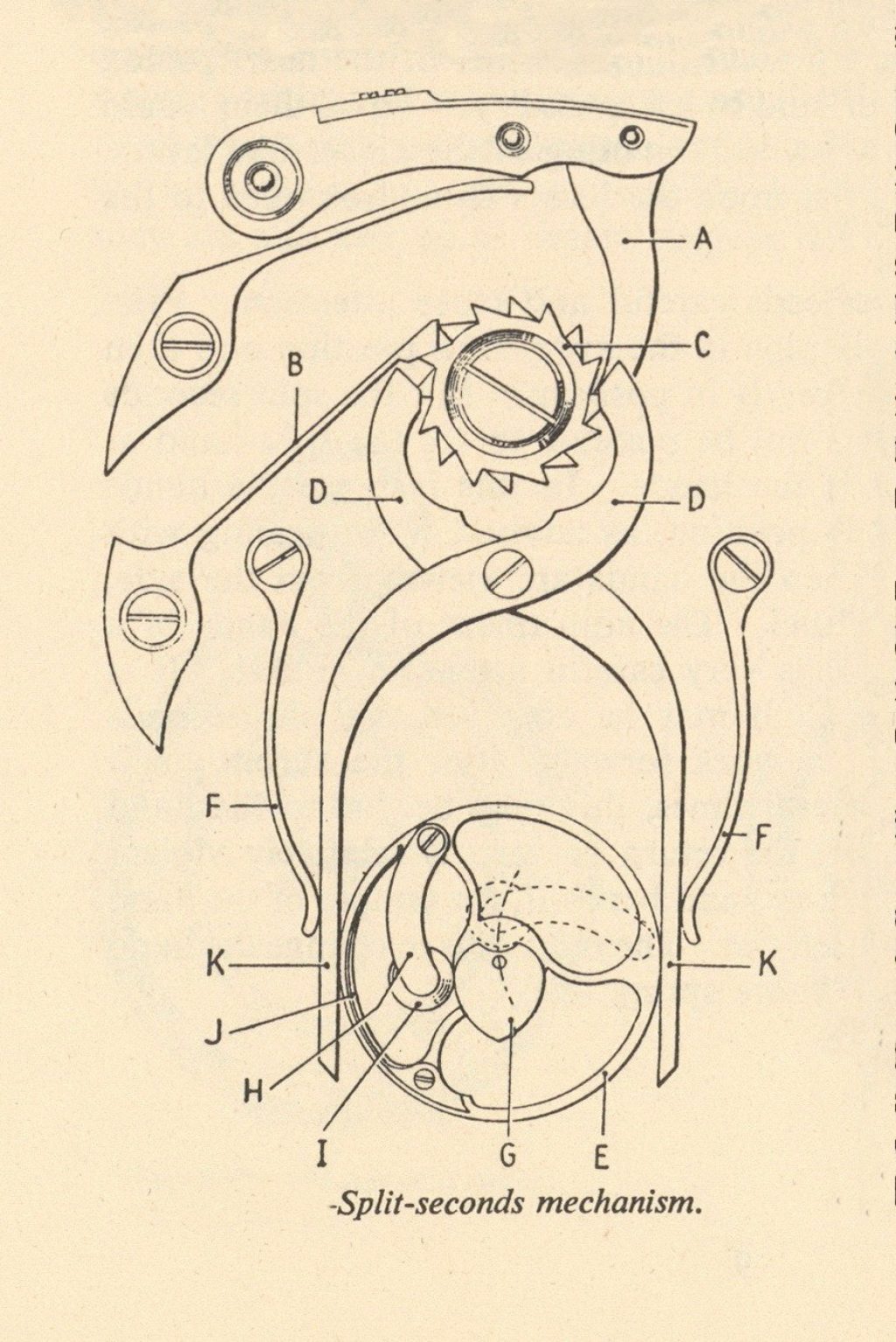

The Traditional Rattrapante

The traditional split-second chronograph has two column wheels, one to control the chronograph (start / stop / reset) and one to control the split-second hand (stopping the split-second hand and then releasing this hand so that it will rejoin the primary second hand).

We can quickly identify a split-second timer by its large “pincers”, which are the brakes that stop and release the wheel that is attached to the split-second hand. A properly adjusted movement is able to stop the split-second hand in an instant, allow the primary second hand to continue running (with no interference from the stopped hand) and then reliably reunite the two hands, as they continue running together.

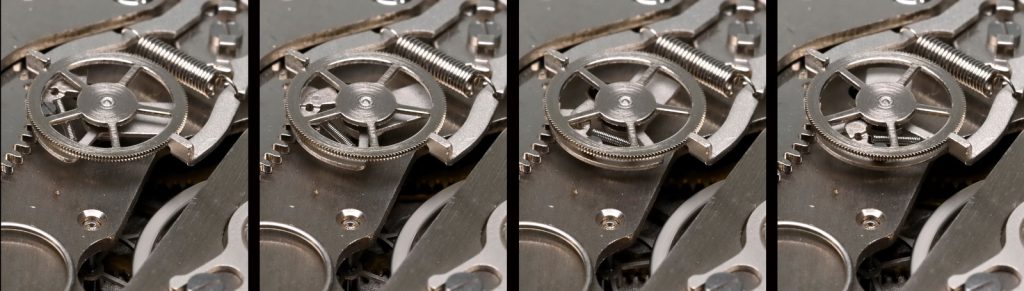

Seeing the split-second column wheel, the pincers, and the wheel that carries split-second hand in action is a wondrous thing. There is a lot of activity of a lot of parts occurring in a very tight space, and any error in the adjustment of these parts will cause problems in the operation of the timepiece. Carole Forestier-Kasapi, Movements Director at TAG Heuer, explains, “On a technical level, it is very difficult to create a reliable split-second chronograph. We are dealing with some very small, intricate parts, and adjustments must be precise. Making these timepieces durable enough for the racetrack or rally car added to the challenge.”

The images above show that, with the “brake engaged”, the wheel that carries the split second hand is stopped, but the wheel that carries the primary second hand is continuing to rotate around the dial.

Democracy versus Haute Horlogerie

Over the last 30 years, we have seen two interesting developments relating to the watch brands offering split-second chronographs. Beginning in 1993, IWC incorporated levers and cams to add a split-second complication to the Vajoux 7750 movement, resulting in “economy” version of the split-second chronograph. While these movements lacked the elegant design and precise feel of the traditional rattrapante chronograph movements, they “democratized” the complication, with IWC and several other brands offering a variety of cam-based models at around the $10,000 price point, with pre-owned versions of various models being available in the $5,000 range.

At the other end of the spectrum, split-second chronographs incorporating the traditional architecture (two column wheels and pincers) have recently been popularized by several of the leading “high-end” brands. Patek Philippe introduced the first split-second chronograph in 1923 (shown below), and currently offers the Reference 5370P at $297,530.

Richard Mille offers the RM65-01 with a movement made by Vaucher at a price of $310,000. And for those wanting more complicated complications, A. Lange & Sohne offers the Double Split and the Triple Split.

With the market dividing into two camps — the “economy” rattrapantes and the haute horlogerie rattrapantes – TAG Heuer puts a chip in its hand and declares that it is going “high” with the newest Monaco.

Yes, it incorporates the traditional architecture, with two column wheels and no cams; yes, the pincers are front and center in the movement; and yes, with the finishing of its movement and other technical features the Monaco takes its place as a haute horlogerie timepiece.

The starting point for the TH81-00 is a Vaucher split-second chronograph movement, with Vaucher having a long track record of producing these movements for brands like Richard Mille and Parmigiani Flourier. From this starting point, TAG Heuer has made significant changes in the design of the movement. Particularly notable is the bridge on which the rotor is mounted, areas of which have been cut away to show more of the movement, including the two column wheels. The resulting “three-armed” bridge has then been decorated with finishing requiring over 30 hours of work.

TAG Heuer has also added high-quality finishing to many components of the movement, using a variety of techniques.

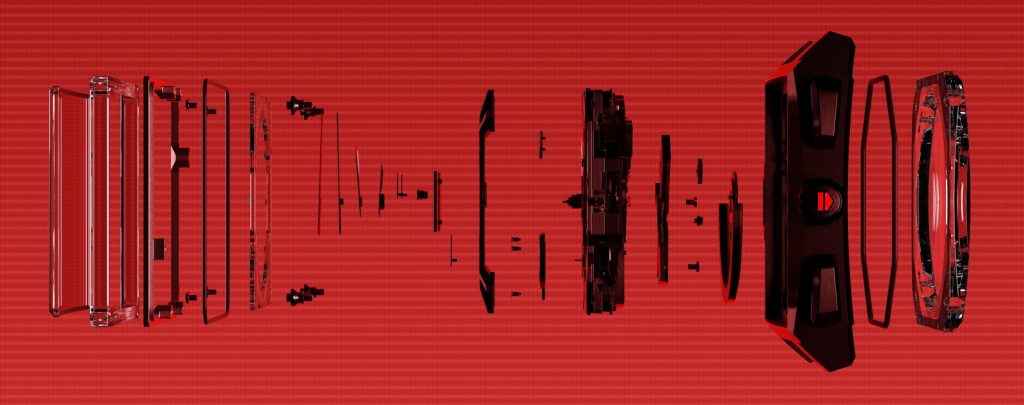

Sapphire Crystals – A Lens, A Plate and a Sculpture

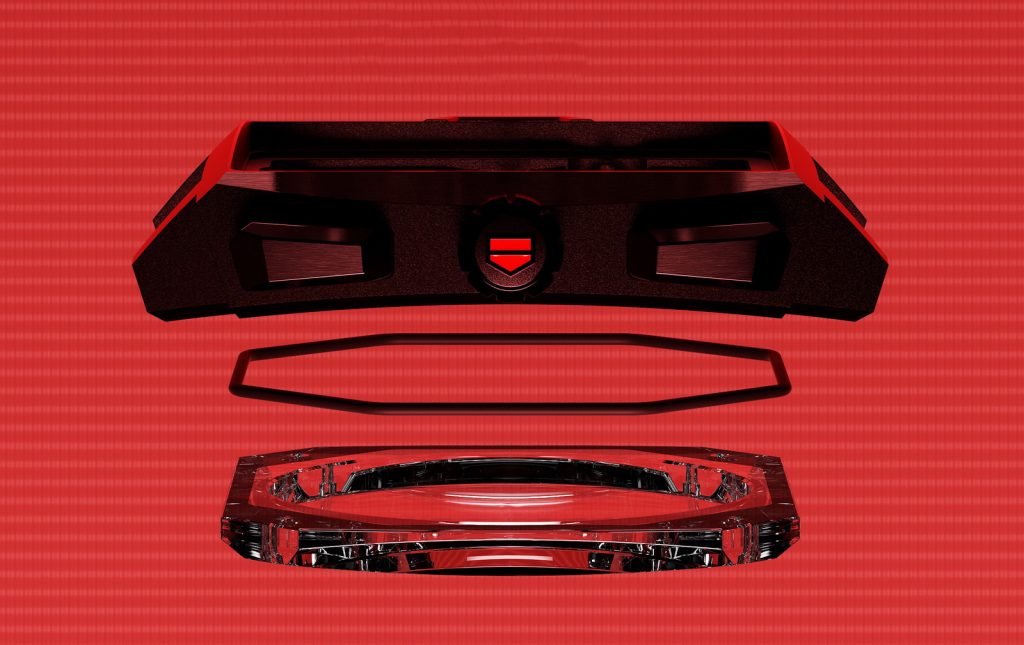

Compared with any other watch previously produced by TAG Heuer, the new Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph makes the boldest use of sapphire. We are accustomed to seeing sapphire used for two crystals – the front crystal that covers the dial and hands and the crystal incorporated into the case-back to create a “display back”. On the newest Monaco, the dial itself is made of sapphire and the entire case-back is a piece of sapphire.

Forestier-Kasapi describes how technical developments over the last few years have allowed the company to use sapphire crystals to improve its chronographs. She states, “The science of creating these large crystals, and then cutting and polishing them for new uses, has developed dramatically over the last five to 10 years. For example, the new Monaco incorporates a sapphire bezel that is extremely delicate, and could not have been produced 10 years ago. Similarly, we would not have seen the large piece of sapphire that functions as the caseback of the new Monaco.”

The Sapphire Case-Back. With TAG Heuer’s introduction in early 2023 of the “second generation” of Glassbox Carrera chronographs, we saw the brand taking a new approach to the function of the crystal on a modern chronograph. The new style of crystal on the second generation Glassbox Carreras went edge-to-edge, effectively displacing the front bezel of the chronograph.

If some enthusiasts suggested that the crystal on the first generation Glassbox Carreras created distortion at certain angles, the crystal on the second-generation Glassbox Carreras addressed this concern. The new Glassbox crystal serves as a lens for the dial and its inner flange (rehaut), as well as for the outer flange, which – depending on the model — may include either markings for the minutes and seconds or a Tachymeter scale.

The new Glassbox Carreras maximize the coverage of the sapphire crystal on the front of the watch, and the new Monaco takes a similarly expansive approach to the crystal on the back of the chronograph. In fact, rather than creating the usual “display back”, comprised of a crystal window in a metal case-back, on the new Monaco the sapphire crystal itself serves as the caseback, being directly attached to what we would normally think of as the mid-case. The interior of the crystal is scooped, so that the rotor actually fits into the crystal, providing the viewer with full visibility of the rotor and movement.

The Sapphire Dial. Perhaps the most novel use of sapphire on the new Monaco Split-Second Chronograph comes with the dial. What we would normally think of as the dial is actually a square piece of sapphire that goes from edge-to-edge in the case, however, a circular center section is “cut out”, with the hour and minute recorders positioned within the cut-out.

These recorders are mounted on three-sides bridges that are attached to pillars at the corners of the dial. The hashmarks for the hours and minutes (and one fifths) are printed on this the sapphire dial, with the dial also providing the base for the hour markers, which done in red paint and super Luminova dots.

The Crystal as Sculpture. When the Monaco was introduced in 1969, it joined the Autavia and the Carrera in Heuer’s line-up of automatic chronographs. The Carrera was a versatile chronograph for racers, a watch that could be used at the track and then worn to a dinner at the club. The Autavia was a pure tool for racers, divers or travelers, with rotating bezels that were marked for minute, hours, decimal minutes, decompression or a second time zone. The Monaco was something entirely different, however, an outrageous piece of sculpture or architecture for the wrist, that also incorporated a chronograph.

The crystal that was used for the original Monaco in 1969 was a complex piece of plastic that complemented and enhanced the architecture of the case. The edges of the crystal that run north / south (from 6 o’clock to 12 o’clock) are straight, to match the top surfaces of the sides of the case. The edges of the crystal that run east / west (from 9 o’clock to 3 o’clock) are curved, matching the curvature of the top surface of the top and bottom surfaces of the case. .

Biebuyck describes the role of the crystal in contributing to the style of the new Monaco. “The original Monaco was really a design object, more than a traditional wristwatch. Think of the materials that were used in “modern” buildings in 1969, and compare them with the materials in today’s modern buildings, and you realize just how much modern materials offer new realms of creativity. It is the same with designing watches. The Monaco was a stunning piece of sculpture back in 1969, and the materials and technology that the artist may use today provide new realms of creativity.”

The Case — A Proper Tribute to the First Monaco

The Monaco was introduced in 1969 and if Heuer was looking to the future with its radically-styled case, history confirms that the company overshot the mark. The Monaco did not sell well, even after Heuer introduced less expensive models in 1972 and 1974, and the model was “closed-out” circa 1975. Indeed, the Autavia and Carrera could be restyled to add some 1970s funk to more traditional models, but the look of the Monaco could not be dialed down to suit more conservative tastes.

The Monaco returned as a re-issue in 1997, and since that time we have probably seen over 100 versions of the model, in a variety of shapes and sizes. Most versions of the Monaco have been larger than the 1969 launch models, consistent with popular demand for larger watches in the current century.

The geometry of the case and crystal of the new Monaco Split-Second Chronograph are true to the design of the original Monaco from 1969. TAG Heuer began with the geometry and size of the original Monaco, and changes in the dimensions to produce the new case were relatively minor.

The “tale of the tape” shows that the dimensions of the new Monaco Split-Second Chronograph are very close to the dimensions of the 1970s Monacos. Looking at the Reference 74033 models, the new Monaco measures 41 millimeters across the dial (compared with 40 millimeters for the 1970s model) and the new case is 15.2 millimeters thick, compared with 14.3 millimeters for the predecessor. The lug-to-lug measurement is the only measurement that differs by more than one millimeter, with the new Monaco coming in at 47.9 millimeters, compared with 45.3 millimeters for the 1970s model.

Nick Biebuyck comments on the style of the new Monaco Split-Second Chronograph, “The look of the new Monaco evokes the energy and excitement of racing, but the devices that we incorporate are not as obvious as some of the elements used on some previous versions of the Monaco. There are no “pistons” holding the movement, “asphalt” on the dial or “racing stripes” on the recorders, but this new sculpture captures the excitement of racing. Some enthusiasts like to see the symbols of racing on their watch while others will appreciate the energy and excitement that the Monaco conveys.”

The Price is Right

Of course, the elephant in the room relating to the new TAG Heuer Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph is the price of the watch, with a base price of $138,000 and up to $30,000 of additional charges for customization. My own view is that we can address this elephant directly, with the view that the price for the newest Monaco seems reasonable when we consider exactly what the timepiece is (and isn’t).

This is a handmade example of haute horlogerie, in the context of the most important and difficult complication in the world of chronographs. Yes, you can go onto eBay and find a pre-owned IWC split second chronograph for less than $6,000, and you can get brand new split-second chronographs in the $10,000 range. But these are not the appropriate comparables for this Monaco.

Carole Forestier-Kasapi comments, “The Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph is the first watch in TAG Heuer’s renewed initiative in haute horlogerie. We are not producing this watch on an “industrial” scale, but this chronograph is the work of a limited number of the most highly-skilled watchmakers. Imagine one watchmaker sitting at their bench with over 380 components, and their objective is to produce one perfect watch. This is a very different undertaking than with the other models in our catalog.”

In looking at split-second chronographs being sold today, Biebuyck is confident that the new Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph belongs with among the very finest models in the category. Biebuyck suggests that the new Monaco is fully comparable to such ultra high-end watches as the Patek Philippe Reference 5370, the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Split Second Chronograph and the Richard Mille RM 65-01 Split Second Chronograph.

When Your Heritage is Your Halo

Watch brands that have glorious histories face a dilemma in considering how they should utilize their heritages in developing new models. When they produce one-to-one copies of their iconic watches, they are accused of lacking creativity. When they use a vintage model for inspiration, but make significant changes from the original watch, they may be accused of misusing or even misappropriating their heritage, even if commercial realities demand certain “updates” of the older models. Whatever approach a brand may be taking, we can expect the press releases and catalogs to refer to the “DNA” of the current model. If only we could actually swab a watch and look for this magical substance.

One of the drawbacks to issuing heritage-inspired watches is the need for the brands to attract attention to their new watches. Over 200 watch brands gather for a few days in Geneva, and we can expect the headlines to be dominated by the brands that are able to produce the most outrageous or the most unexpected watches. For a TAG Heuer Monaco, Omega Speedmaster, Rolex Submariner or Breitling Navitimer to capture a headline, the brand will need to overcome the presumption that whatever watch it is introducing has already been done before.

With the new Monaco Split-Second Chronograph, TAG Heuer has shown us an important approach by which a storied watch brand can use its heritage to produce a compelling watch. Rather than being constrained by the four corners of its heritage portfolio, TAG Heuer has taken some of the very best chapters of its history, embodied them in a watch and then given them new life and energy by incorporating modern materials and technologies that will excite a new generation of enthusiasts.

For over a century, Heuer has been a leader in motorsports timing, with its precision stopwatches and split-second stopwatches and chronographs used by race teams and officials. Now we see TAG Heuer developing a new split-second chronograph movement that incorporates the traditional architecture – with the beloved pairs of column wheels and pincers – but the new chronograph is constructed of titanium, a very modern material. As many watch brands seek to leverage their connections to motorsports, TAG Heuer reminds us of its unmatched credentials on the racetrack.

The Monaco was an outrageous piece of sculpture that captured the mood of the 1970s, even if it didn’t prove to be popular as a wristwatch. By recasting this sculpture in titanium and sapphire TAG Heuer shows us that the 50-year-old shape remains modern.

With patents that were filed circa 1915, Heuer used high frequency movements to provide precision 1/50 and 1/100 second stopwatches, with a split-second option. The Monaco that TAG Heuer has introduced today runs at 36,000 vibrations per hour, which has become the standard for high-frequency movements in the modern era.

In the 1950s, Heuer redesigned the favorite tool of the racing and rally crowd to offer enhance legibility and a protective carrier, in a 57 millimeter case, with the bright white dial with large black Arabic numerals replacing the previous Breguet numerals and hands. Today, TAG Heuer has created a “hybrid” case of titanium and sapphire that will feel right on the wrist, while displaying its beautifully-decorated titanium movement.

Reviewing these elements shows us that the approach that TAG Heuer used throughout its history — in 1915 and in 1958 and in 1969 and in 1982 — remains a winning formula in the year 2024. Making precision watches that are rugged and legible, that look good to the eye and feel good on the wrist, and that incorporate modern materials and techniques, is the formula for success in the world of chronographs and sports timing. Enthusiasts have favored these timepieces for 164 years and they continue to favor them today. On April 9, 2024, it’s great to be adding the rattrapante chronograph, the “queen of complications” to the formula.

The Basics – TAG Heuer Monaco Split-Second Chronograph

TAG Heuer is offering two versions of the Monaco Split-Seconds Chronograph, one with a Black DLC coated titanium case (and red accents) and the other with a titanium case (and blue accents) as follows; both cases are brushed, sandblasted and polished:

- On Black DLC model, arches are black DLC; registers are black opalin; hands on chronograph recorders and split-second hand are red lacquered

- On uncoated titanium model, arches are gradient blue; registers are white opalin; hands on chronograph recorders are blue lacquered; split-second hand is blue gradient

Movement is the Calibre TH81-00, running at a frequency of 5 Hertz and with a power reserve of 65 hours (chronograph off) or 55 hours (chronograph running)

Case measures 41 millimeters across the dial, 47.9 millimeters from lug-to-lug, and 15.2 millimeters thickness.

Jeff Stein

April 9, 2024