In 1953, Chevrolet introduced the Corvette, America’s first true sports car. Fourteen years later, the L-88 option package turned the Corvette into a factory-built racecar that would compete in international endurance racing. This is the story of how the Sunray DX racing team and car builder / racer Don Yenko successfully campaigned the L-88 Corvette in the 1967 / 1968 racing seasons.

We also tell the story of the Heuer Carrera chronograph with “Sunray DX Motorsports Division” printed on the dial, which is being sold by Sotheby’s in its Fine Watches auction, February 29, 2024 through March 12, 2024. The catalog listing for this Carrera is HERE.

Summer of 1966, Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

It’s the Summer of 1966 in a small town in Southwest Pennsylvania, and Gary’s interests are typical for a young man about to turn 21. He loves things that go fast — boats on the lake, cars on the road, and airplanes in the sky. After two years of college, he is trying something different, flying school in Oklahoma.

His friend’s mother drives a Corvette, and Gary enjoys visiting the nearby Chevrolet dealership, Yenko Chevrolet, in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Don Yenko, whose father owned the dealership, had the reputation for being the guy who could build the Corvettes to make them go really fast. Yenko could also drive Corvettes really fast, having won Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) national championships in 1962 and 1963.

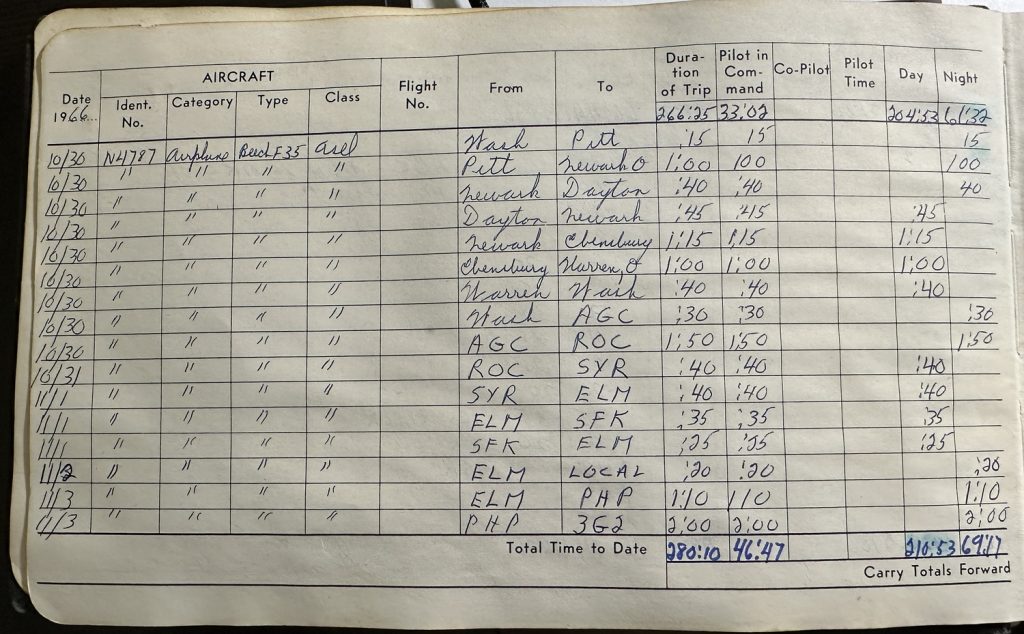

Gary was in flying school and needed to get more as a pilot; Don Yenko had a plane and needed a pilot. One thing led to another and soon Gary was working as a pilot for Don Yenko, flying him to racetracks and running errands for the dealership.

When Don Yenko joined the Sunray DX racing team in 1967, Gary also joined the team as a driver, but rather than driving Corvettes, Gary was driving the hauler that carried the Corvettes to racetracks and on promotional trips. The 1967 season proved to be a great success for Sunray DX and Don Yenko, as Yenko and Dave Morgan won the GT class at the 12 hours of Sebring and Morgan went on to win a regional championship in the SCCA.

Toward the end of the season, Don Yenko showed Gary the brand new Heuer Carrera that he had received from the manager of the Sunray DX team. Printed on the white dial were “Sunray DX Motorsports Division” and the red, white and blue Sunray DX logo. The team manager promptly gave Gary one of these watches, with the words, “you earned it.”

Now age 78, Gary will be selling this Heuer Carrera through Sotheby’s in its Fine Watches Auction being held February 29 through March 12, 2024. In this posting, we’ll tell you more about Gary, his friend Don Yenko, the fastest Corvette on the planet (circa 1967) and the racing team that brought all this together.

Young Gary cherished his time with Don Yenko and the Sunray DX racing team, and always enjoyed wearing this special memento. Now it’s time for some other adventurer to wear this particular Carrera, but first we’ll tell you how things played out for Gary.

Don Yenko – Building the Fastest Chevrolets in America

Don Yenko was born on May 27, 1927, in Bentleyville, Pennsylvania, where his father opened a Chevrolet dealership in in 1934. Don had a passion for flying, receiving his pilot’s license at age 15, and serving in the United States Air Force. While in college, Don was active in flying, music, theatre and debate.

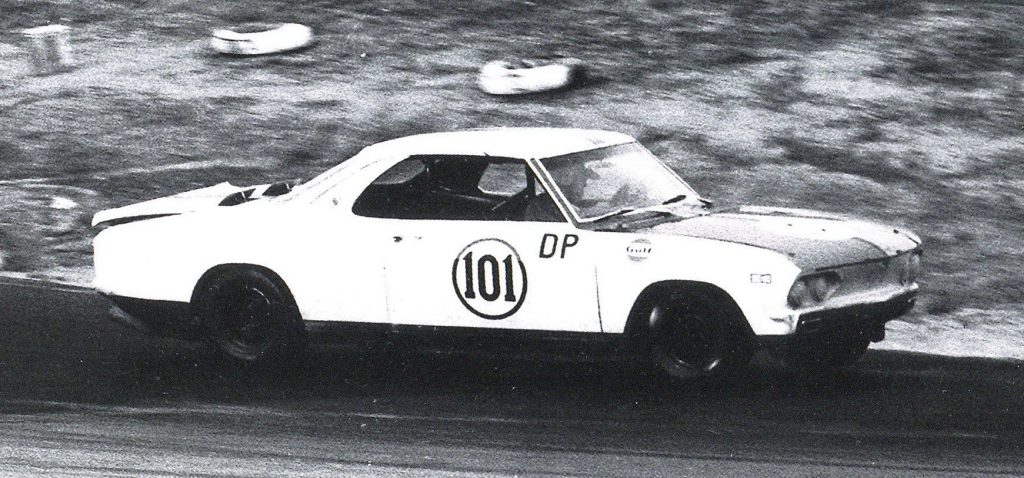

In 1947, Yenko Chevrolet would open a second location, in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, approximately 15 miles from Bentleyville, and Don would manage this operation. The younger Yenko had a reputation as the man who could tune the Chevrolets so that they would be the fastest of their breed. Customers from across the country would order their Corvettes, Corvairs, Novas, and Camaros from Yenko Chevrolet, specifying the modifications that they wanted made to their cars.

In 1965, Yenko Sportscars modified 185 Corvairs, to produce up to 240 horsepower, marketing them as “Stingers”. With the introduction of the Chevrolet Camaro in 1967, Yenko had a new specialty, improving their performance, including through the installation of the L-72 Corvette engine.

More than tuning cars to go fast, Don Yenko could also drive them fast. Yenko began racing relatively late in life, entering his first races in in 1957 and finding success immediately. Gulf Oil fielded its first racing team in 1961, and perhaps because of his good connections with Chevrolet, Yenko got a spot as a driver, driving the #3 Corvette Grand Sport. Yenko won the SCCA national championship in B-Production in 1962 and 1963, driving Corvettes both years.

Don Yenko had an aggressive, fearless style, driving with abandon. He was not shy about wrecking his cars, being known to pick up the pieces in baskets and take them back to Yenko Chevrolet, where the car would be put back in running order. For Don Yenko, if he broke it on Sunday, then his mechanics at Yenko Chevrolet could fix it on Monday.

In this period, Don Yenko – through his dealership – became a critical hub in the relationship between the Gulf Oil racing program and the Chevrolet Motor Division. Direct corporate sponsorship of “amateur” racing drivers was not permitted by the SCCA, but it could prove beneficial for a racer to have a good relationship with a dealership that had good connections to Chevrolet. However contorted the sponsorship and financial arrangements between Gulf Oil, Yenko Chevrolet and the Chevrolet Motor Division may have been, Don Yenko was successful on the track, as was another Gulf Oil-sponsored driver, Dr. Dick Thompson.

Sunray DX Oil Company — Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday

With the emergence of stock car racing in the 1950s, automakers embraced the “Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday” approach. Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile, Ford, Mercury, Plymouth, Dodge and Crysler sedans competed as stock cars, with many of the cars carrying the names of dealerships, in the largest possible letters. Stock cars were full-size sedans, and the Sports Car Club of America soon followed with races for a wide variety of sportscars and smaller sedans.

The oil companies soon followed along with the “Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday” campaigns. The racecars of the 1950s were relatively sterile, but by the early 1960s, corporate funds (and corporate decals) were flowing to the racing teams. The top sponsors (largest decals) were usually the carmakers or large dealers, but the oil and gas brands soon made their way onto the cars, with “Pure” being the most common of the oil company sponsors, circa 1960.

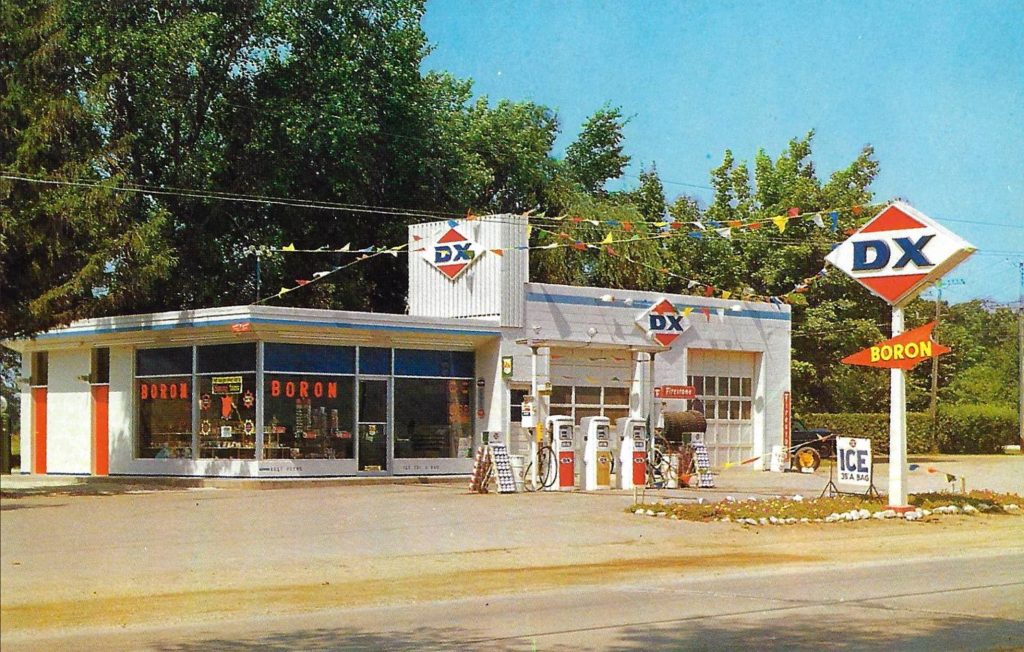

Founded in 1916, as Mid-America Petroleum company in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the company’s gas stations were rebranded as Sunray D-X following the 1955 merger with Sunray Oil Company, with red, white and blue as the corporate colors. Sunray DX positioned itself as a brand that offered high performance fuel and oil products, with D-X Boron and D-X Super Boron as the company’s premium and super premium grades. By the mid-1960s, Sunray DX was the sixth largest oil company in the United States.

The Sunray DX racing program began modestly, with the company sponsoring regional races in Oklahoma and Arkansas in 1965 and 1966. Sunray DX provided prize money and trophies for the competitors, and oil and gas for the cars. For 1967, any racers displaying the Sunray DX decal and finishing at the top of the field would receive prize money.

Decals, oil and gas, and prize money were a good way for Sunray DX to get into the racing game, but for the 1967 racing season, the company would go all-in, buying and building its racecars, and running and funding a full-time racing program. Rather than competing at regional or even national races, Sunray DX would quickly move up the hierarchy of racing, setting its eyes on the world’s most important endurances races. At this time, the “triple crown” of endurance racing was comprised of the 24 Hours of Daytona (usually contested in February), the 12 Hours of Sebring (typically held in April) and the 24 Hours of Le Mans (held in June).

In this period when the car manufacturers were not allowed to sponsor racing teams, a Chevrolet dealer like Yenko might be an important partner in the racing enterprise, having access to cars, as well as the parts and mechanics that would improve their performance. The Sunray DX team purchased its first car through Yenko Chevrolet, and Don Yenko would serve as the team’s lead driver and car builder.

As it turned out, 1967 proved to be a good time for Sunray DX to field a racing team built around the Chevrolet Corvette, as Chevrolet was ready to introduce what would become one of the most dominant racecars in the history of American sports car racing.

America Goes Racing – The Corvette and the Cobra (1953 to 1966)

As the American automobile industry emerged from World War Two, something was missing. American automobile manufacturers were producing full-size sedans for growing post-War families, but there was nothing cool or sporty about these cars. The European automobile companies were offering a wide range of smaller cars that combined attractive styles with strong performance. In the early 1950s, the grids of the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the 12 Hours of Sebring were comprised of European sports cars from manufacturers such as Ferrari (Italy), Jaguar (England) and Talbot Lago (France), with none of the American manufacturers participating in sports car racing.

On January 17, 1953, at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, 45,000 people gathered for the General Motors “Motorama” automobile show. All GM brands participated in the show, but a small white car from Chevrolet quickly became the talk of the event. It was a running prototype of the Corvette, and the tremendous enthusiasm of the crowd for this car led senior Chevrolet executives to make the decision to move quickly to produce the Corvette.

Zora Arkus-Duntov, a 43-year-old, Belgian-born, unemployed engineer and race driver, attended the “Motorama” show and was smitten by the Corvette. While impressed with the beauty of the Corvette, Duntov was disappointed by the mechanical features of the car, which were mainly derived from current Chevrolet models. Duntov was determined to get a job at Chevrolet, with the objective of turning the Corvette into a high-performance sports car.

Duntov went to work for Chevrolet as an assistant staff engineer, on May 1, 1953, and he continued as the “Chief Engineer of the Corvette” until he retired in 1975.

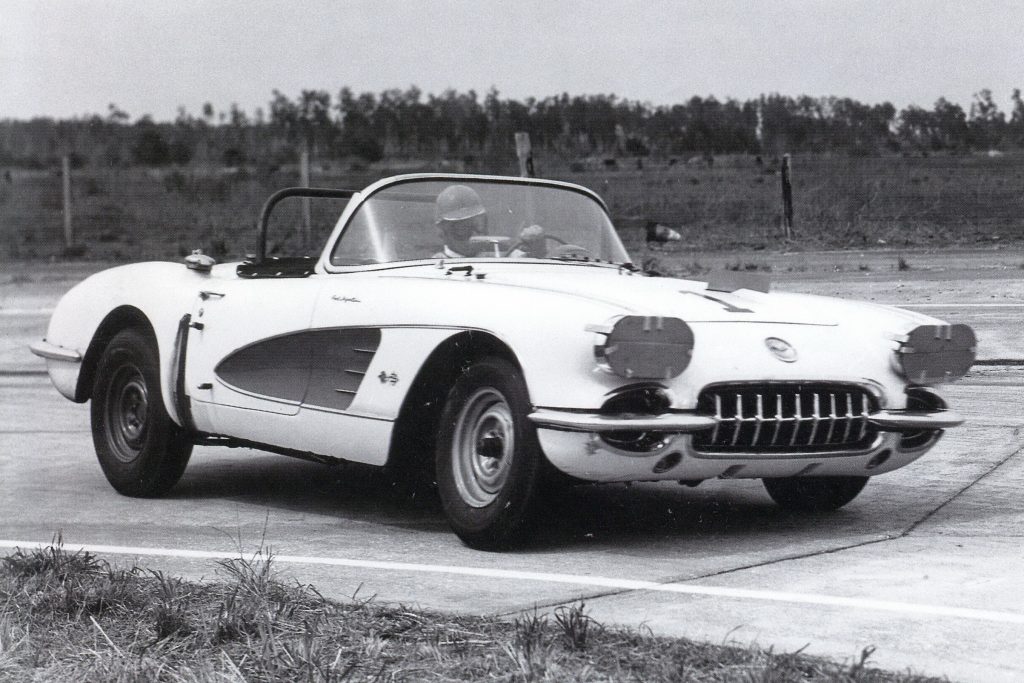

It didn’t take long for the Corvette to go racing, with Duntov leading the charge. In November 1954, a Corvette participated in the Carrera Panamericana, the road race across Mexico.

In the 1956 12 Hours of Sebring, Corvettes were the only American entrants, finishing 9th, 15th and 23rd in the field comprised mainly of Ferraris, Porsches, Maseratis and Jaguars. For 1957, four Corvettes were the only American cars to compete at Sebring, with three of them finishing in the top 16 positions, including a win in the Grand Touring class.

Beginning in 1957, sports car racing in the United States would face a severe restriction, as the Automobile Manufacturers Association issued a ban on the manufacturers fielding racing teams or publicizing racing results. This followed the tragic crash at Le Mans in 1955 that killed a driver and 83 spectators. Despite the ban on racing, the automobile manufacturers could develop high-performance production cars, as there were plenty of “privateers” to purchase these cars and field racing teams in both the professional and amateur series. The first generation (C1) Corvettes enjoyed good success in the late 1950s and early 1960s. At Sebring in 1958, a Corvette finished 12th overall (and fourth among the GTs); at Le Mans in 1960, a Corvette finished eighth overall and fifth among the GT cars, racing behind four Ferrari 250 GTS cars.

The sports car racing landscape changed dramatically in 1962, when Carroll Shelby stuffed a Ford V8 engine under the hood of an AC sports car to create the Shelby Cobra. At Sebring in 1963, six Cobras (with their 289 cubic inch engines) faced off against seven Corvettes (with 427 cubic inch engines), with the top Cobra winning the GT class and finishing 10 laps ahead of the fastest Corvette. At the 1964 Sebring race, the Cobras took five of the top 10 positions overall, including four of the top five positions in the GT class. The top Corvettes were far back in the field, with the top two cars placing 16th and 18th overall.

In the battle between Chevrolet and Ford to sell cars, being beaten by the Cobra was not an acceptable position for the Corvette. However, with the Cobra being 50% lighter than the Corvette, Chevrolet realized that no amount of tweaking or engine-building could make the current Corvette competitive. Instead, under the leadership of Zora Arkus-Duntov, Chevrolet built a version of the Corvette (called the “Grand Sport”) that would be 37% lighter than the standard Corvette.

The Grand Sports used a complex steel space frame and fiberglass panels for the bodywork, weighing in at around 1,900 pounds, compared with 3,250 pounds for a standard Corvette. Its 377 cubic inch engine put out 550 horsepower. In December 1963, at Nassua Speed Week, it was “mission accomplished” for the Grand Sports Corvettes, with Dick Thompson finishing fourth overall, with the top Cobra finishing seventh.

Duntov planned to build 100 Grand Sports to satisfy the FIA’s homologation requirements and enable the Grand Sport to compete on racetracks around the world. Shockingly, Chevrolet pulled the plug on the Grand Sport program, after only five cars had been completed. Duntov had built the Corvette that could beat the Cobras, but corporate politics at Chevrolet dictated that the Grand Sports would never compete in international GT races.

1967 — Meet the L-88 Corvette

It was only in 1967 that Chevrolet and Arkus-Duntov were able to create the Corvette that they had been hoping to build – a thinly disguised racecar that would be offered as a production model through dealerships, but with pricing and marketing that would keep the car in the hands of racers, not suburban commuters.

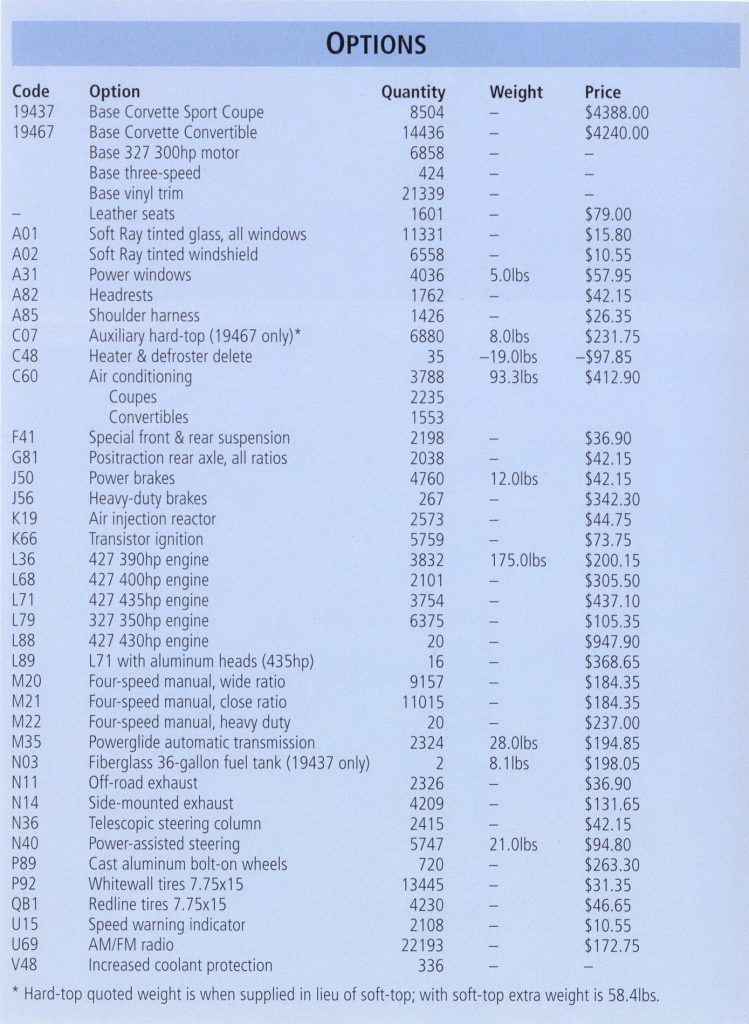

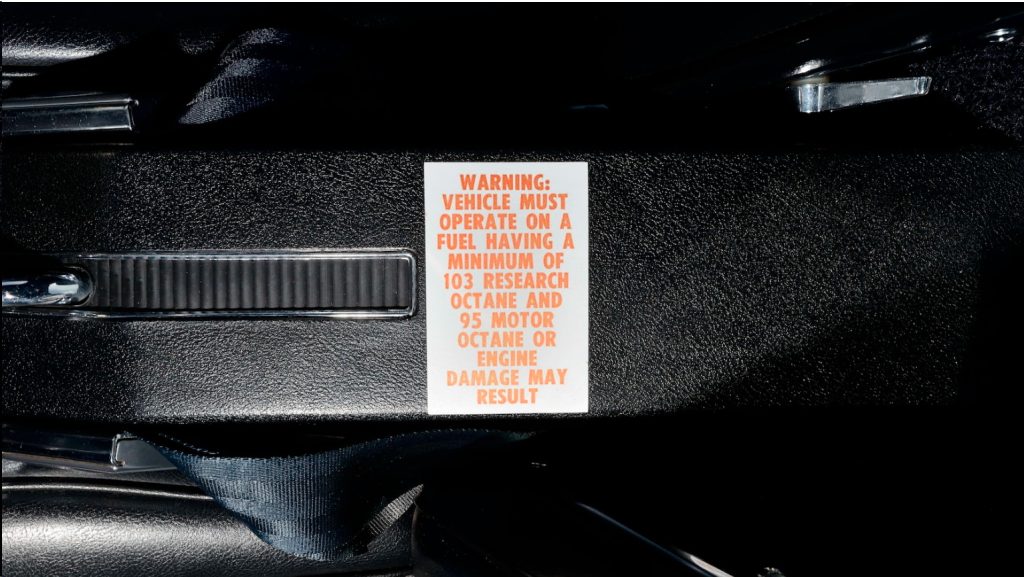

Chevrolet offered the L-88 engine as a “regular production option” (RPO) for the 1967 model year, The L-88 engine was a 427 cubic inch engine rated at 430 horsepower, with aluminum heads and aluminum intake manifolds.

Key components included in the L-88 package included a heavy-duty close ratio four speed transmission, a power-boosted braking system, with heavy duty calipers and pads and a front-to-rear proportioning valve, a special air cleaner and cowl induction hood, and a heavy duty suspension with heavier springs, shock absorbers and anti-sway bars. Fuel flowed through a special 850 cubic feet per minute Holley carburetor; a newly-designed radiator cooled the L-88 engine.

Duntov designed the L-88 package for racers and racetracks, not for ordinary street use, and Chevrolet incorporated some marketing sleight of hand, to try to keep ordinary customers away from the cars. Chevrolet stated that the engine produced 430 horsepower at 5,400 RPM, while a good tuner and open exhaust could take the stock L-88 engine to 560 horsepower. Pricing of the L-88 package would also deter the casual commuter, as the engine and other mandatory options included in the package added over $1,700 to the $4,388 base price of Corvette. The “deletions” from standard models might also deter the casual driver – no power steering; no heater / defroster or air conditioning; no choke on the carburetor; and no fan shroud on the radiator.

A final deterrent was the fuel requirement, with Chevrolet indicating that the L-88 engine, with its 12.5 to 1 compression ratio required fuel with at least 103 octane, hardly the stuff of the neighborhood gas station.

As one writer has noted, “The aluminum headed 427, in concert with an M22 “Rock Crusher” transmission, heavy duty brakes and suspension, and a host of other competition-inspired hardware, turned the Corvette into the purest race car to ever roll off a Detroit assembly line.”

The Sunray DX Racing Team — 1967 and 1968 Campaigns

Chevrolet would produce only 20 of the L-88 Corvettes in the 1967 model year, but Don Yenko’s good standing with Chevrolet allowed him to secure delivery of the very first production L-88 Corvette for the Sunray DX team. Yenko’s co-driver Dave Morgan picked up the car at Chevrolet’s St. Louis assembly plant on March 9, 1967, giving Don Yenko and his crew three weeks to prepare the car for its initial outing at the 12 Hours of Sebring, on April 1, 1967.

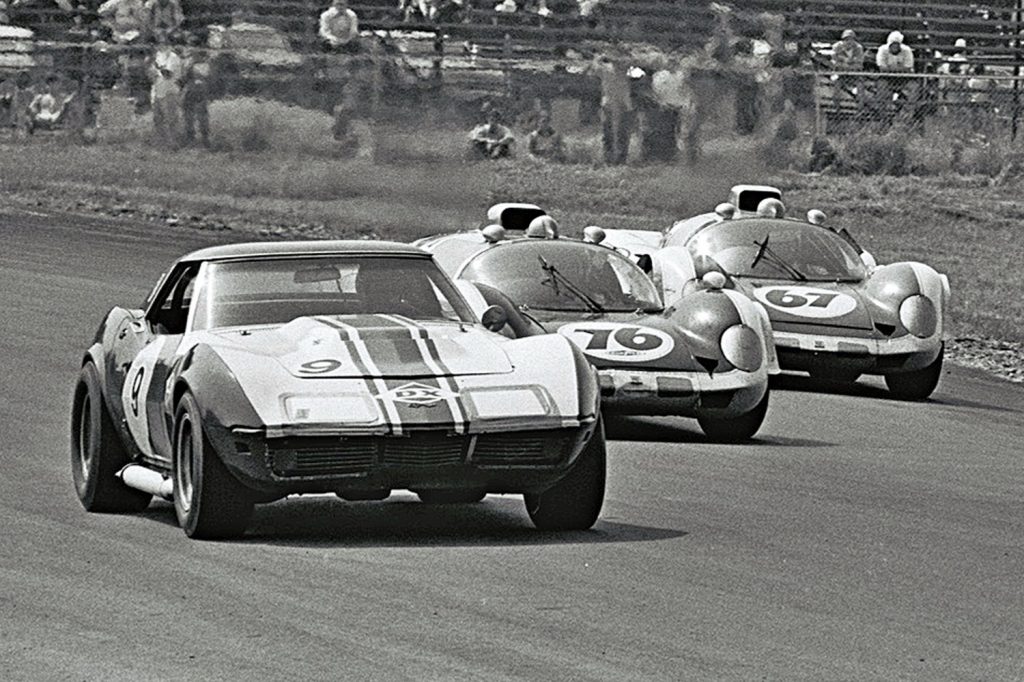

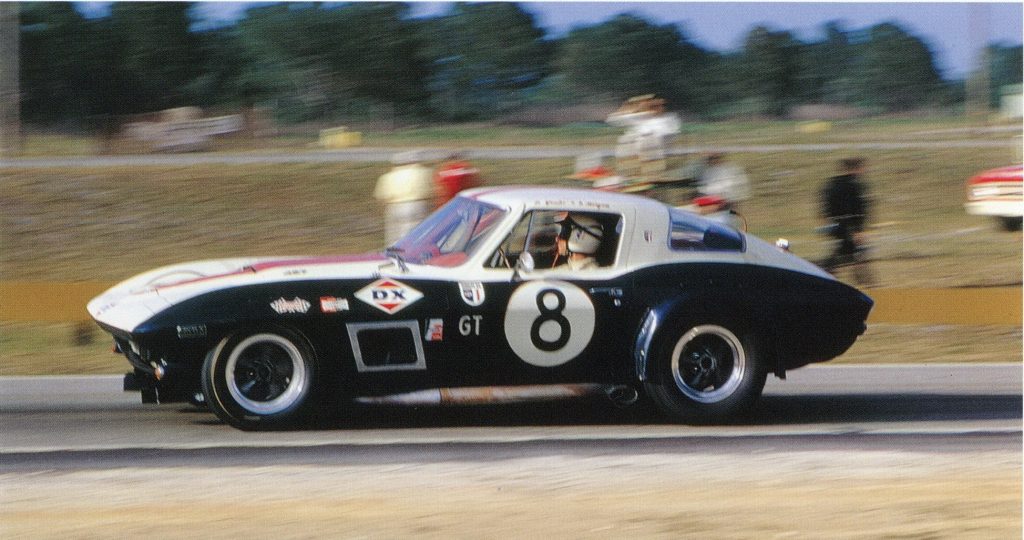

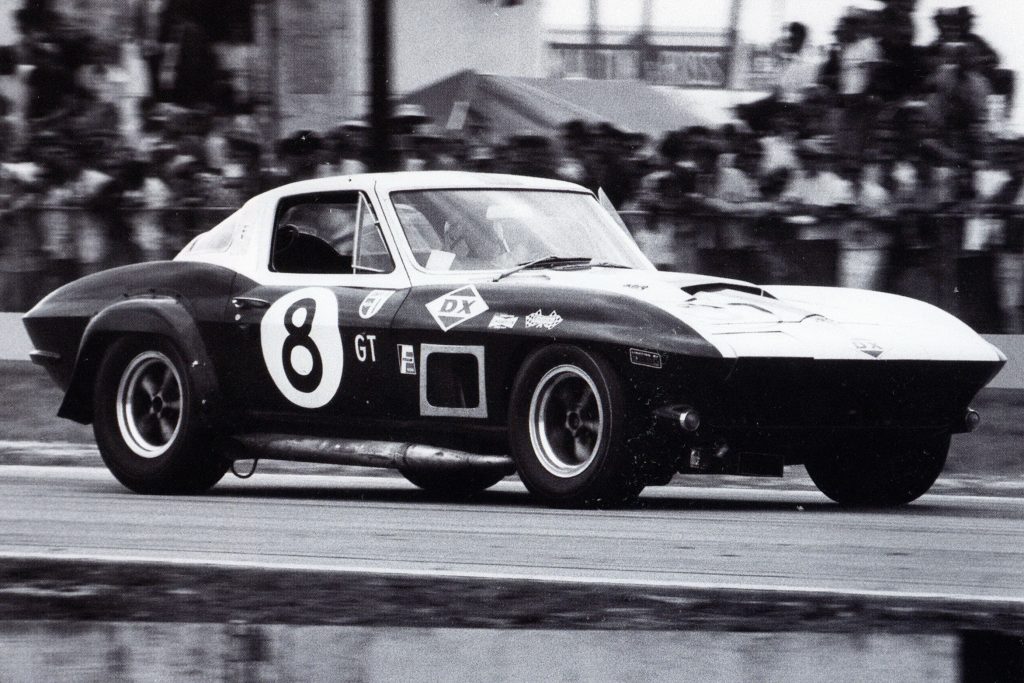

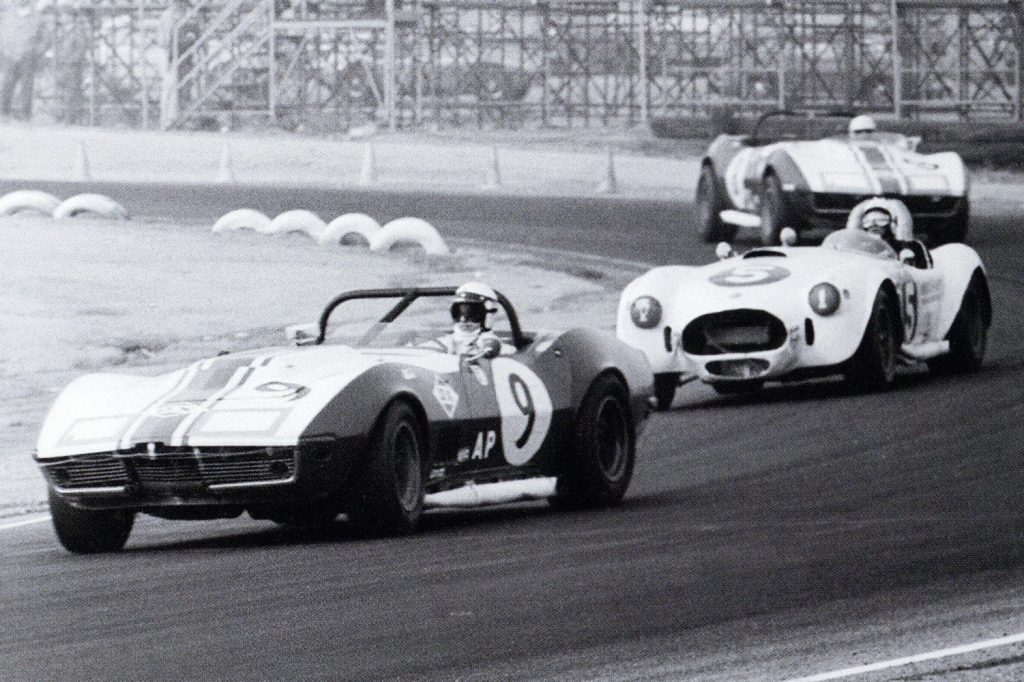

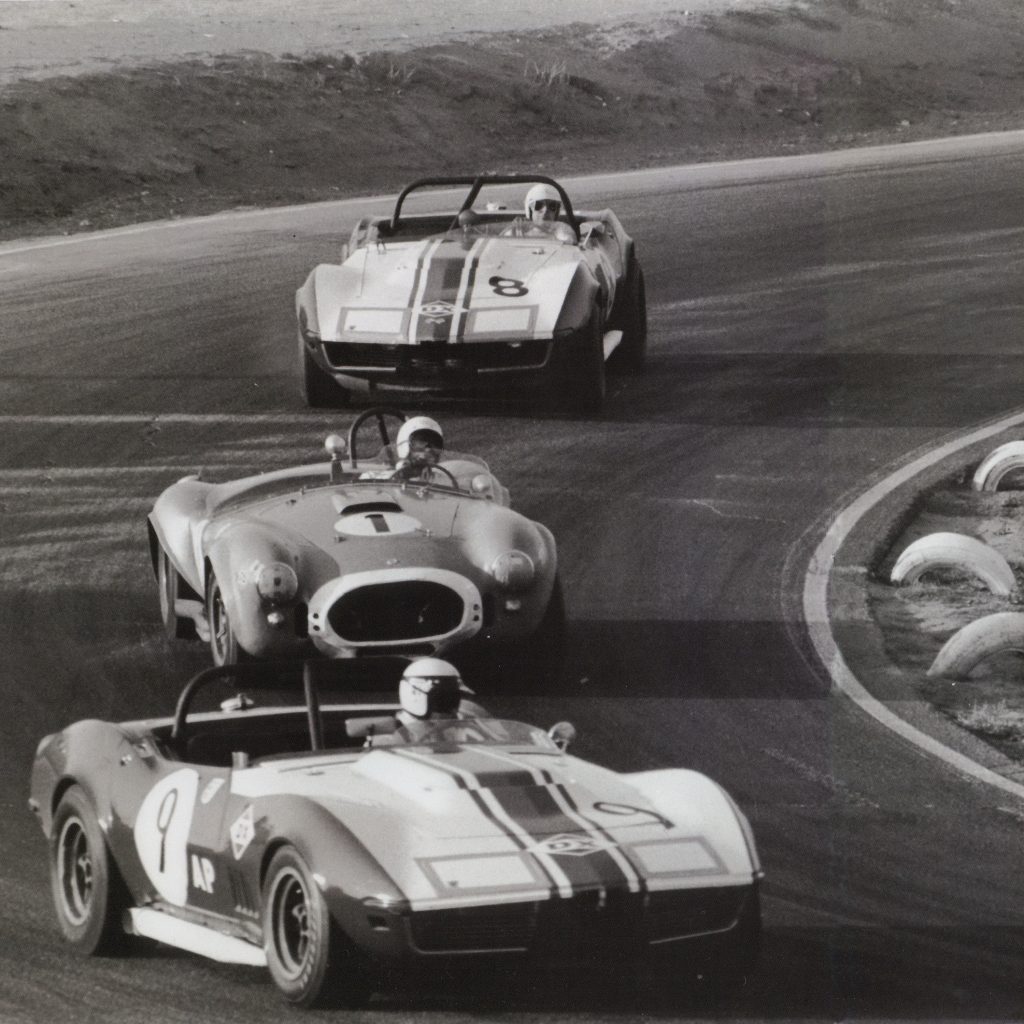

As the Sunray DX entry, the L-88 Corvette was painted white and blue, with red stripes, and would carry the number 8. Telltales that a production car had been hopped up to become an all-out racecar included larger rear wheel arches to cover the racing tires, side exhaust pipes and large air extractors in the front fenders.

April 1967 – 12 Hours of Sebring. Don Yenko and Dave Morgan drove the Sunray DX Corvette at its initial outing, finishing the race with a first place finish in the GT class, 10th place among all competitors in the race. Other leading GT cars included the Porsche 911, Shelby GT 350, Ferrari GTB/4 and Jaguar XKE. The Sunray DX Corvette hit a top speed of 190 miles per hour, a record for GT cars at Sebring.

June 1967 – 24 Hours of Le Mans. For the June 1967 running of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Sunray DX sponsored a Corvette that was owned by Botany, a maker of men’s clothing, and campaigned by Dana Chevrolet, a dealership in South Gate, California.

At the insistence of Chevrolet, the L-88 Corvette raced at Le Mans was completely stock, with only safety equipment added to the standard production car. The car was prepared by noted Corvette engineer, Dick Guldstrand, with Bob Bondurant as his co-driver. The car (#9) was leading the GT class when it retired in the 13th hour (on lap 167). As at Sebring, the Sunray DX Corvette attracted considerable attention, breaking the record for the fastest lap by a GT car and hitting 180 miles per hour on the Mulsanne Straight.

1967 SCCA Racing. Dave Morgan drove the Sunray DX Corvette in SCCA races, winning the A Production championship in the Midwest Division. The A Production class included Corvettes, as well as Mustangs and Shelby Cobras.

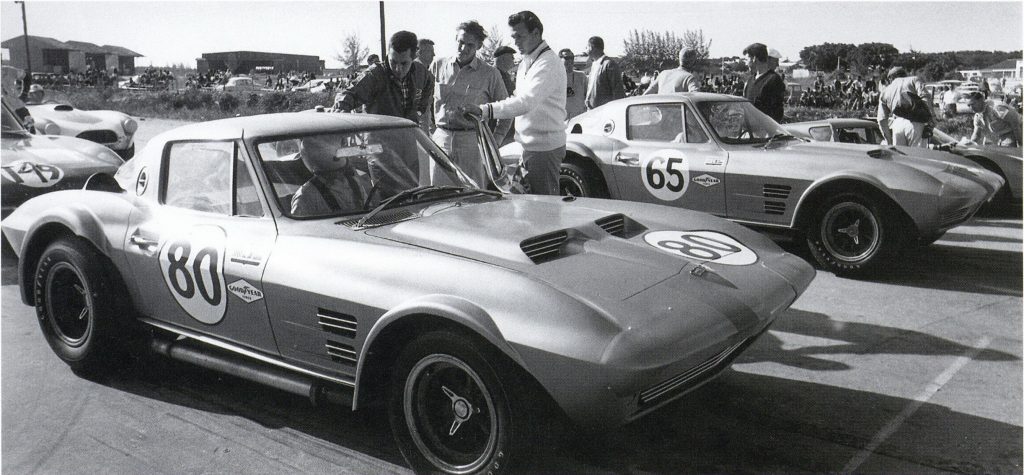

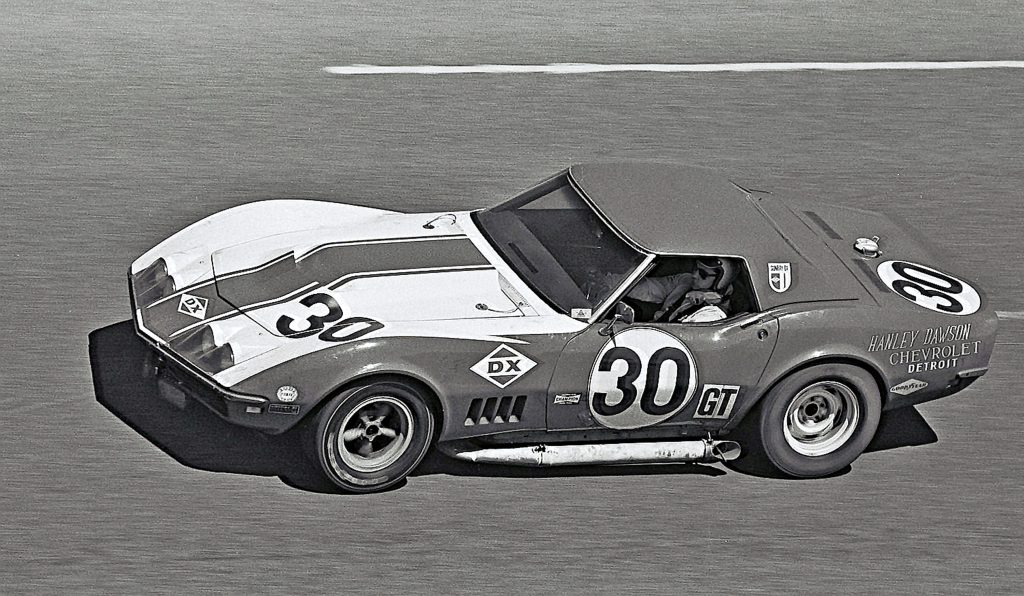

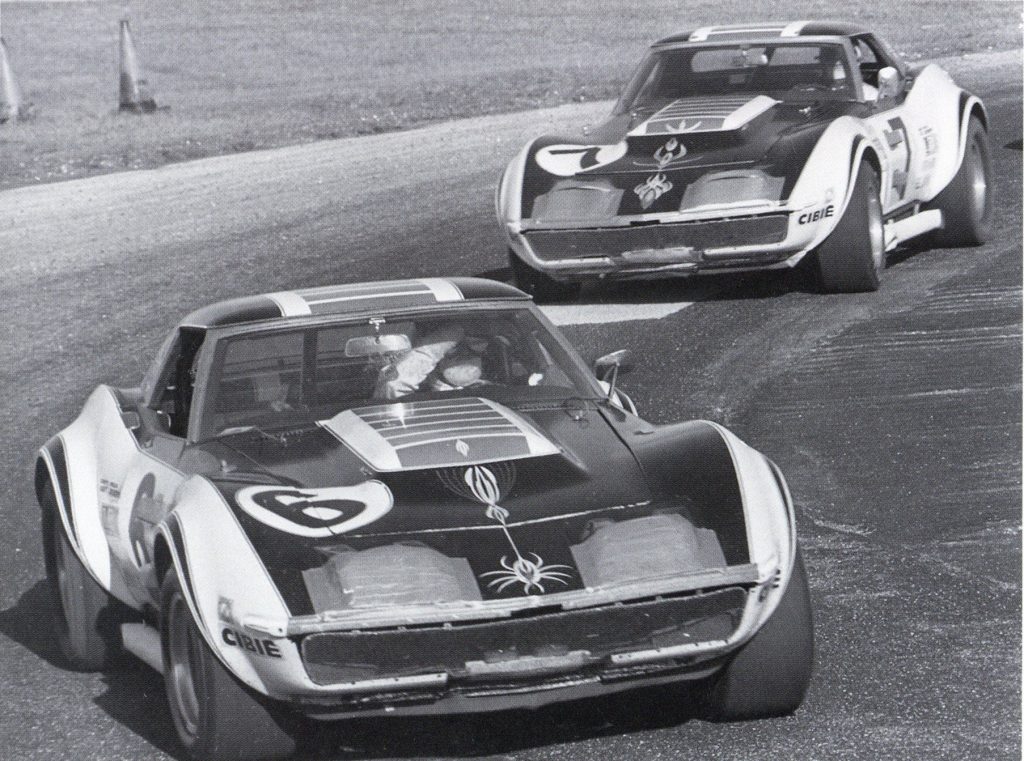

1968 Season Preview. The performance of the Sunray DX racing team during the 1967 season yielded considerable benefits for the company, so for the 1968 season, Sunray DX would up the ante, moving to a team that would enter three cars in each of the major endurance races. In addition to the L-88 coupe from the 1967 season, Sunray DX would enter two 1968 L-88 roadsters. The 1967 Corvettes were the last year of the second generation body style (C2, known as the “Stingray”), with the new 1968 models being the first year of the third generation (C3) “Shark” style cars.

February 1968 – Daytona 24 Hours. At Daytona, Dave Morgan and Jerry Grant drove the 1967 model (now carrying # 31). The new 1968 cars would be driven by Yenko and Peter Revson (# 29), and Tony DeLorenzo and Jerry Thompson (# 30). Ironically, it was the old reliable 1967 model that ran best at Daytona, with Morgan and Grant finishing first in the GT class and 10th overall, exactly the same positions this same car had taken in its debut at Sebring, in the previous season. The Yenko / Revson car finished 4th in the GT class (25th overall); the DeLorenzo / Thompson car was 5th in the GT class (27th overall).

Regardless of where the three cars finished in the standings, toward the end of the race they moved into formation for an iconic photo showing the three Sunray DX L88 Corvettes running side-by-side on the dramatic banking of the Daytona International Speedway. For Sunray DX and the Chevrolet Corvette, this was the “money shot” that offered an attractive yield on their investment in racing. Indeed, this was the ultimate “Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday” image.

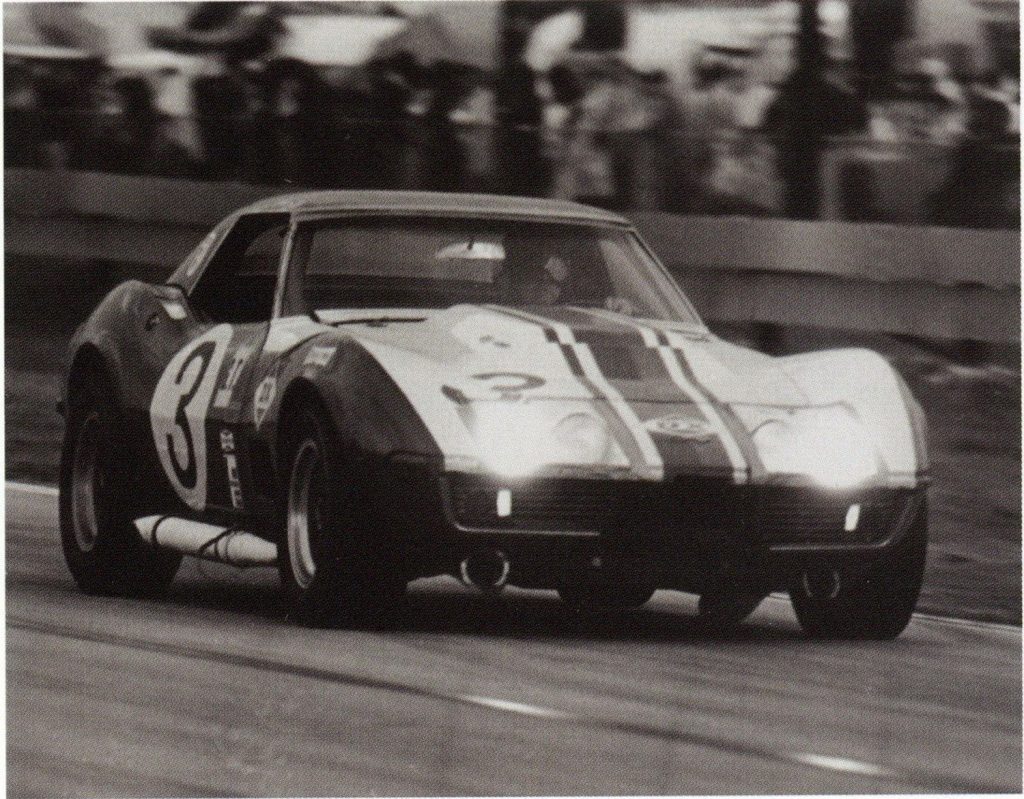

March 1968 – 12 Hours of Sebring. The following month, for the 12 Hour race at Sebring, a brand new 1968 L88 Corvette (#3) would replace the accomplished 1967 model, which was retired by the team. Dave Morgan and Hal Sharp drove the car to a win in the GT class, with the 6th place overall finish being the highest ever for a Corvette at Sebring. The other two Sunray DX entries failed to finish the 12 hours, the # 4 car of DeLorenzo and Thompson losing its drive shaft on lap 48, and the # 2 car driven by Yenko and Pedro Rodriguez retiring with engine problems on lap 43. The Yenko / Rodriguez car had the fastest time in qualifying, being 10 seconds faster than the Yenko / Morgan Corvette from 1967.

Author Peter Gimenez has noted that with the victory of the Sunray DX Corvette at Sebring, and the St. Louis plant having increased capacity to produce the cars, Corvettes with the L88 package were “falling into the hands of enthusiasts and racers, which resulted in even more wins at racetracks around the country.” After producing only 20 of the L-88s for the 1967 model year, production grew to 80 cars in 1968 and 116 cars in 1969. Chevrolet clearly enjoyed the halo effect of the L-88 racing program, with strong sales of the Camaro, Chevelle and Nova models.

June 1968 – 24 Hours of Le Mans. For the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Sunray DX team had planned to enter the new Corvette that Yenko / Rodriguez had driven at Sebring, along with a second Sunray DX Corvette. Because of civil unrest in France, however, the race was moved to September 1968. By this time, Sunray DX had been acquired by Sun Oil, so Yenko and his Sunray DX teammates were never able to compete in the premier event in endurance racing.

1968 SCCA Season. A six-hour race at Watkins Glen in July 1968 would be the last major endurance race for the Sunray DX team, with Don Yenko and Dave Morgan driving a 1968 roadster, until being knocked out by an accident on Lap 84.

The final appearance of a Sunray DX sponsored racecar came at the Sports Car Club of America national championship, held at Riverside Raceway in November 1968. The 30-minute race turned into a wild shootout between the L88 Corvettes and the 427 Cobras, with Don Yenko leading the race in the early laps, but falling behind the leaders after a 360 degree spin and eventually finishing fifth.

With this, the brief but brilliant campaign of the Sunray DX L88 Corvettes came to a close. It seems entirely fitting that the last appearance of an L-88 Corvette in the Sunray DX livery would come with a handful of the Corvettes doing battle with the Cobras, in a race that featured multiple lead changes and wild spins.

Fifteen years after Chevrolet introduced America’s first sports car, in the hands of Don Yenko and the Sunray DX racing team, this sports car had reached the pinnacle of racing success, taking on all comers, whether at Le Mans, Sebring and Daytona, or the local racetracks.

Gary — A Pilot’s Pilot

In October 1966, just after his 21st birthday, our friend Gary was hired by Don Yenko as a pilot, to fly Yenko to races and to fly various business “errands” for Yenko Chevrolet. Don Yenko needed to travel for business and there were often parts and packages to be picked up or delivered.

When Don Yenko became a member of the Sunray DX racing team, in early 1967, Gary also signed on with the team, driving the truck that would transport the Sunray DX Corvette to races, as well as to promotional events. The calendar of promotional events was especially busy throughout the year, as the Sunray DX Corvette made numerous appearances at events for the Sunray DX brand. There were events for Sunray DX franchisees and customers, and members of the public were excited to see the Sunray DX racing Corvette. Gary sums up his primary responsibilities for the Sunray DX racing team. “I was wherever the car was. For a race weekend, I would drive the hauler from our home base in Pennsylvania or wherever we were coming from to the track. When the car was part of a marketing appearance, I was there with it, often telling visitors about the car and the latest Sunray DX oil and gasoline products.”

During race weekends, at the track Gary would serve as a spare set of hands for the Sunray DX racing team, doing whatever might be helpful for the team or Don Yenko. Gary would regularly handle the signal board, communicating with Yenko as he passed the pits. There were also the routine errands and tasks when he might be able to help the team. Gary recalls, “For a 22-year-old guy who loved flying planes and being part of sports car racing, this was a pretty good job. The L-88 Corvettes were spectacular cars, that ran well on the track, looked great and were very popular with fans, all around the country.”

Gary also comments on his relationship with Don Yenko. “Don was a mentor to me. Whether he was working on a car, flying a plane, playing the piano or hanging out with the crew at the track, Don was a special man. He was 18 years older than me, and always showed an interest in teaching me, whether about planes or cars or life itself. There is a special bond between two guys up in an airplane, at night in a storm, trying to figure out how to get back home safely. Those were good times.”

Fall 1968 – Going Their Own Ways

The end of the year 1968 saw the end of the collaboration that had brought glory upon the Sunray DX racing team, those magnificent red, white and blue L-88 Corvettes, and Don Yenko and his co-drivers.

With the merger of Sunray DX into Sun Oil (also called “Sunoco”), Sunray DX stations and brands would soon carry the Sunoco name and the Sunray DX racing program would be absorbed into the very successful Sunoco program.

The Corvettes continued to enjoy great success, in both international endurance races and the full range of American events. In November 1969, Corvettes took six of the top seven spots in the American Road Race of Champions. The 1970 12 Hours of Sebring saw Corvettes take the top two spots in the GT class, finishing 10th and 11th overall. At the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Corvettes finished 15th overall in 1972, 12th and 18th overall in 1973 and 18th overall in 1974.

Don Yenko would continued racing Corvettes and Camaros, winning the GT class at Sebring in 1969 and Daytona in 1971, with additional podium finishes at Sebring in 1970 and 1972 and Daytona in 1975. Yenko finished second in the SCCA’s American Road Race of Champions in 1969. Perhaps Yenko’s greatest racing accomplishment was winning the Citrus 250, at Daytona in 1968, driving a Camaro to finish ahead of Parnelli Jones (Mustang), Lloyd Ruby (Camaro), Joey Chitwood (Camaro) and Bob Tullius (Javelin).

The high-water mark of his business modifying cars may have come in 1969, when he produced Corvettes, Camaros, Chevelles and Novas. Don Yenko died at in 1987, at age 59, when the plane that he was piloting crashed while landing in Charleston, West Virginia.

Gary moved from Pennsylvania to Florida in September 1968, had a long career in law enforcement, with the Ft. Lauderdale Police Department.

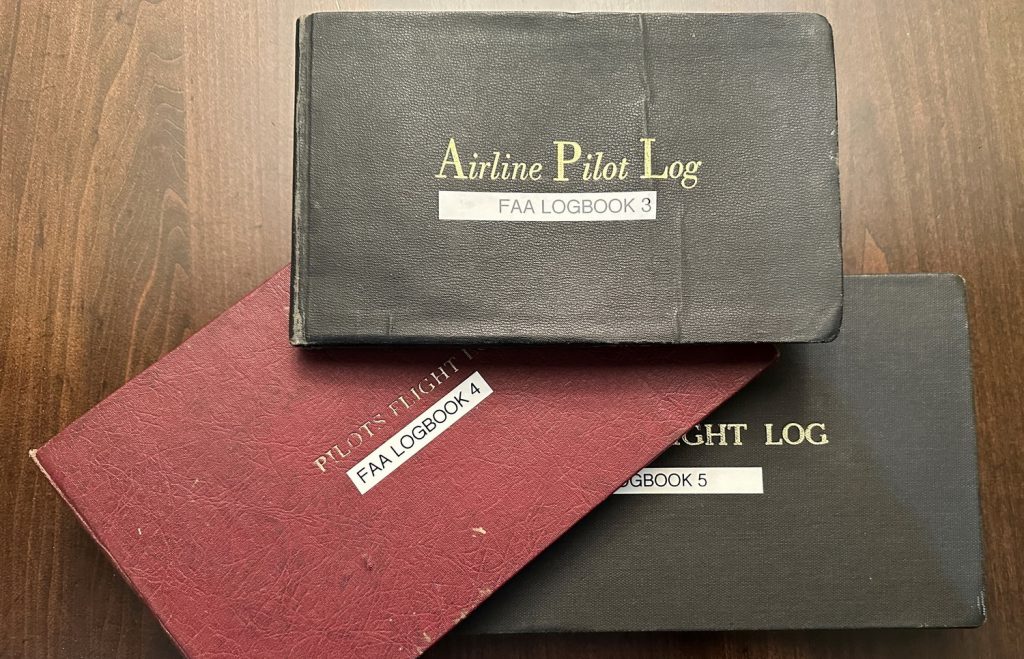

Gary has logged over 8,000 hours as a pilot, including flying several types of airplanes and helicopters as part of his law enforcement duties. The Sunray DX Carrera that Gary received from the Sunray DX team back in 1967 was on his wrist for most of those hours.

Gary comments, “For the past 55 years, looking at the Carrera chronograph with that Sunray DX logo on the dial has brought back some great memories of my relationship with Don Yenko and the Sunray DX racing team. It’s interesting to look back at the logbooks and remember some of the adventures.

I’m hoping that the next guy to own this watch will be enjoy this connection to a great period of sportscar racing and racers, and one hell of a car and team.”

The Heuer Carrera, Reference 3647 T (Sunray DX Dial)

Heuer introduced the Carrera in 1963, as a chronograph specifically designed for racing. Named after the Carrera Panamericana de Mexico, the road race across Mexico, staged from 1950 through 1954, the Carrera chronograph was designed to be rugged, legible and easy for the driver or navigator to operate, while racing.

The first models of the Carrera, from 1963, had either white or black dials, and either two or three registers. While legibility dictated that the dials of the Carreras should be free of clutter or decoration, Heuer did offer dials with either a Tachymeter or Decimal Minutes scale. The Tachymeter scale allowed the racer to convert the time over a measured distance (mile or kilometer) into the rate of speed for that distance (miles per hour or kilometers per hour).

The Carrera Reference 3647 T (Tachymeter) has a white dial, with a Tachymeter scale printed in red toward the edge of the dial. The inner bezel / tension ring (rehaut) is marked in one-fifth seconds / minutes, allowing the racer to take precise readings.

The Carrera being sold by Sotheby’s as Lot 90 in its Fine Watches Auction has the serial number 72620, which suggests that the watch was produced circa 1967. Gary believes that the Sunray DX racing team ordered 12 of these watches and gave them to members and friends of the team.

The bracelet currently on the watch replaced the original Corfam strap and this bracelet was not made by Heuer.

Don Yenko — Carrera Guy

In this photograph from 1971, Don Yenko is wearing a Carrera 30, Reference 7753 NS. This is the “reverse Panda” model, with a black dial and white registers.

References

Books

Corvette Racing Legends, The Story of the L-88 Option Package, by Rd. Peter J. Gimenez, Vettura Publishing Ltd. (2008)

Corvette Thunder, 50 Years of Corvette Racing, 1953 – 2003, by Dave Friedman, Guldstrand Motor Productions (2003)

Sebring, the Official History of America’s Great Sports Car Race, by Ken Breslauer, David Bull Publishing (1995)

Yenko, The Man, The Machines, The Legend, by Bob McLung, CarTech, Inc (2010)

Websites

Racing Sports Cars — a database that provides information about races and racers; accessed February 29, 2024

Thanks

We sometimes look at the old watches and wish they could tell us their stories. Sincere thanks to Gary for telling us the story of his time with Don Yenko and the Sunray DX racing team. Thanks also to our good friends at Sotheby’s for introducing me to Gary and sharing information about his special watch.

Jeff Stein

February 29, 2024

Photo Credits

[to be added]