|

World's First Automatic Chronograph ---------------------------------------- This webpage presents Parts One and Two of a three-part series of articles covering the history of the Chronomatic / Caliber 12 chronographs.

This webpage is an adaptation of Parts One and Two of the series, and includes additional photographs and documents that did not appear in the print versions of the articles. This page will be updated from time to time, as additional information becomes available. As always, I would welcome any questions, comments or additional information and documents. Jeffrey M.

Stein Copyright Jeffrey M. Stein, 2008, all rights reserved.

Many think of the

1960's as the golden age of motor racing.

The cars were fast; the tracks were

wide-open; the finishes were close; the

drivers were heroic, challenging death as

they challenged each other.

As much as

anything, racing in the 1960's was

characterized by the rivalries -- between

teams and between drivers. Porsche,

Ferrari and Ford at Le Mans; Porsche

versus McLaren in CanAm; the Camaros and

Mustangs on the TransAm circuit; and Lotus

and Ferrari in Formula One. There were the

heroic drivers - Andretti, Brabham, Clark,

Donahue, Foyt, Gurney, Hill, Hulme and

McLaren, among many others.

While the teams

and cars battled throughout the decade,

many of the rivalries between the drivers

were destined to last for only a short

while. Study the starting grids in the

early 1960's, and you realize how few of

the leading drivers were still racing by

the end of the decade. Many of the leading

drivers were killed; others realized that

the odds had turned against their survival

and took early retirement from what was

called the "cruel sport". Just as the

1960's might be thought of as the golden

age of competition in motor racing, this

was a memorable decade for chronographs

and the other "tool" watches. Specialized

watches were worn by drivers and their

crews when they went racing; by pilots and

international travelers as they crossed

the time zones; by divers on underwater

adventures; by the adventurers as they

climbed the tallest peaks and traveled to

the poles. The "Big Three"

of chronographs -- Omega, Breitling and

Heuer -- competed intensely with each

other, but each brand also established a

distinctive position in the market. Omega

introduced the Speedmaster in 1957; five

years later, astronaut Wally Schirra wore

one in space. By the end of the decade,

the "Speedy" was worn on the moon.

Breitling proclaimed that it was the

world's leading manufacturer of precision

instruments for aviation, with the

Navitimer becoming a part of the pilot's

uniform and the Cosmonaute becoming the

first chronograph worn into space.

Heuer was the

most dominant brand for the automotive

crowd, offering chronographs for the

racers, dashboard instruments for the

navigators, stopwatches for the crews, and

handheld, split-second chronographs for

the race officials. Indeed, "tool

watches" seemed to be coming into their

own in the early 1960's, with the leading

brands developing purpose-built watches

and chronographs for an increasingly wide

variety of demanding applications.

The

Challenge While the Swiss

watch companies continued to develop their

chronographs and other specialized

watches, at the beginning of the 1960's

they faced significant challenges. Sales

of Swiss chronographs were declining from

year to year; the legendary Valjoux and

Venus movements that powered leading Swiss

chronographs were growing old, and -- most

notably -- automatic (self-winding)

watches were enjoying increased popularity

and sales. Automatic watches

thrived throughout the 1950's, as Swiss

manufacturers introduced dozens of new

calibers. Winding systems included

full-rotors mounted to the back of

movements, "bumper" rotors that bounced

back and forth, and micro-rotors to allow

for thinner movements. The very names of

new automatic watches evidenced the

industry's excitement with the automatic

movements -- Datomatic, Depthomatic,

Geomatic, Gyromatic, Kingmatic, Powermatic

and Tempomatic, to name a few. There was

even Jaeger-LeCoultre's Futurematic, which

took the bold step of deleting the winding

/ setting crown, as if to announce that

crowns were a thing of the past. With the

increasing popularity of automatic

watches, the chronograph manufacturers

faced an imperative -- they could either

develop automatic chronographs or they

would continue to see the erosion of their

annual sales. The

Automatic is the Future. In the

1950's, the automatic watch was

the future. This Futurematic went

so far as to delete the winding /

setting crown. Commencing in the

mid-1960's, four leading watch

manufacturers engaged in the race to

develop the first automatic chronograph.

Much like Russia and the United States

competed to plant the first flag on the

moon, or like Ford set out to beat Ferrari

at Le Mans, Heuer, Breitling, Zenith and

Seiko set out to produce the world's first

automatic chronograph. Heuer and Breitling

worked in a unique partnership; Seiko and

Zenith each worked alone. The

Rivals Zenith. In

retrospect, it seems curious that Zenith

joined in the competition to develop an

automatic chronograph. Founded in 1865,

Zenith had established its reputation

during the 1940's and 1950's as a

manufacturer of chronometers and watches

for the military. As a true manufacture,

Zenith produced its own movements for its

chronometers. Still, Zenith offered only a

limited line of chronographs and Zenith

sourced the movements for its chronographs

from other companies, primarily Excelsior

Park. Zenith's relatively small presence

in the world of chronographs is evidenced

by the fact that Zenith was not a member

of the Swiss association of chronograph

manufacturers. In 1960, Zenith

acquired Martel Watch Company, a producer

of movements for chronographs and other

complicated watches (such as calendar and

moonphase watches). Martel was well-known

as the supplier of chronograph movements

for Universal Geneve and other respected

brands. By acquiring Martel, Zenith

broadened its offering of chronographs,

and enhanced its capabilities in the

design and production of chronograph

movements. Soon after its acquisition of

Martel, Zenith adapted the Martel

chronograph movement that had been used in

the Universal Geneve caliber 285 to become

the Zenith 146 series of movements,

featuring the 146-D (a two-register

movement, with 45-minute capacity) and the

146-H (a three-register, tri-compax

movement with a 12-hour

recorder). After

Zenith acquired Martel, in 1960,

it had the capacity to produce

movements for its chronographs,

including the 146H movement.

Soon, Zenith would go much

further, as it sought to produce

the world's first automatic

chronograph. Zenith embarked

on the design of an automatic chronograph

in 1962, hoping to introduce this

revolutionary chronograph to mark the

company's 1965 centennial. Seiko. Founded in 1881,

as a manufacturer of clocks, Seiko

manufactured its first wristwatches in

1913, with the "Seiko" name first

appearing on a watch dial in 1924. In

1955, Seiko produced Japan's first

automatic wristwatch, and in 1960, the

company launched its Grand Seiko line of

watches, designed to represent the highest

development of Japanese watches.

In

1964, Seiko introduced its very

first chronograph (Reference

5717), a one-button timer with 60

second capacity. With the

production of more accurate

watches in the mid-1960's,

including the King Seiko and

Grand Seiko, the company was

prepared to challenge the Swiss

watch manufacturers in both

watches and

chronographs. To bolster its

international reputation for quality, in

the mid-1960's, Seiko began to compete in

the Swiss Observatory Chronometer

competitions, enjoying remarkable success

in these endeavors, and bringing worldwide

recognition to the company. Nineteen

sixty-four was a momentous year for the

company, as Seiko was the official

timekeeper of the Tokyo Olympic Games, and

also introduced it first chronograph, a 60

second timer, with a rotating bezel

(Reference 5717). With its success in

manufacturing rugged, accurate mechanical

watches, Seiko positioned itself to

challenge the dominance of the Swiss watch

industry (even before the advent of quartz

watches). Heuer Founded in 1860,

Heuer introduced the first "wrist

chronographs" around 1914, and had a

long-standing reputation in the production

of chronographs and sports timing

equipment, especially stopwatches,

split-second timers and timing systems.

From pilots'

chronographs in the 1930's, to triple

calendar chronographs in the 1940's, to

rugged chronographs in the 1950's, Heuer

offered a broad range of chronographs. In

1958, Heuer introduced its Master Time and

Monte Carlo dashboard timepieces, and soon

these "Rally Master" pairs were used by

over half the leading rally teams. In the

early-1960's, Heuer introduced two

chronographs that would be popular with

the racers -- the Autavia and the Carrera

-- both of which were powered by Valjoux

movements. Ironically, Heuer also produced

a line of automatic watches, but the

company abandoned these watches in the

late-1950's, in order to focus on the

production of chronographs. Buren Founded in

1873, the Buren Watch Company developed

numerous calibers over the years, always

manufacturing its own parts. Buren

introduced its first automatic watch in

1945, and from the start was seeking to

develop thinner automatic movements. Its

Caliber 525 utilized a pendulum winding

mechanism, recessed within the movement,

rather than a rotor at the back of the

movement. Ultimately, this approach was

not successful, so 1952 saw Buren's first

use of an automatic watch powered by a

rotor. In 1953, Buren offered the smallest

automatic watch with a power reserve

indicator. Origin

of the Species. With Buren's

development of micro-rotor

powered movements,

Charles-Edouard Heuer began to

believe that a modular automatic

chronograph might be feasible. By

placing a smaller rotor in the

same plane as the other movement

components, designers avoided the

additional thickness of a

full-sized rotor. In 1954, Buren

patented its "micro-rotor", which allowed

it to produce the flattest possible

automatic watches. By shrinking the

diameter of the rotor (to fit within the

radius of a comparable movement), and

locating this rotor in the same plane as

other components of the movement, Buren

avoided the need to place the rotor behind

the movement. Buren's first watches using

the micro-rotor were the "Super Slenders"

(calibers 1000 and 1001), introduced in

1957, with this automatic system also

known as the "Intramatic" system.

Buren also

licensed its technology to other

companies, including IWC, Baume &

Mercier, Bulova and Hamilton. After a

patent dispute, Buren also began to

license its micro-rotor technology to

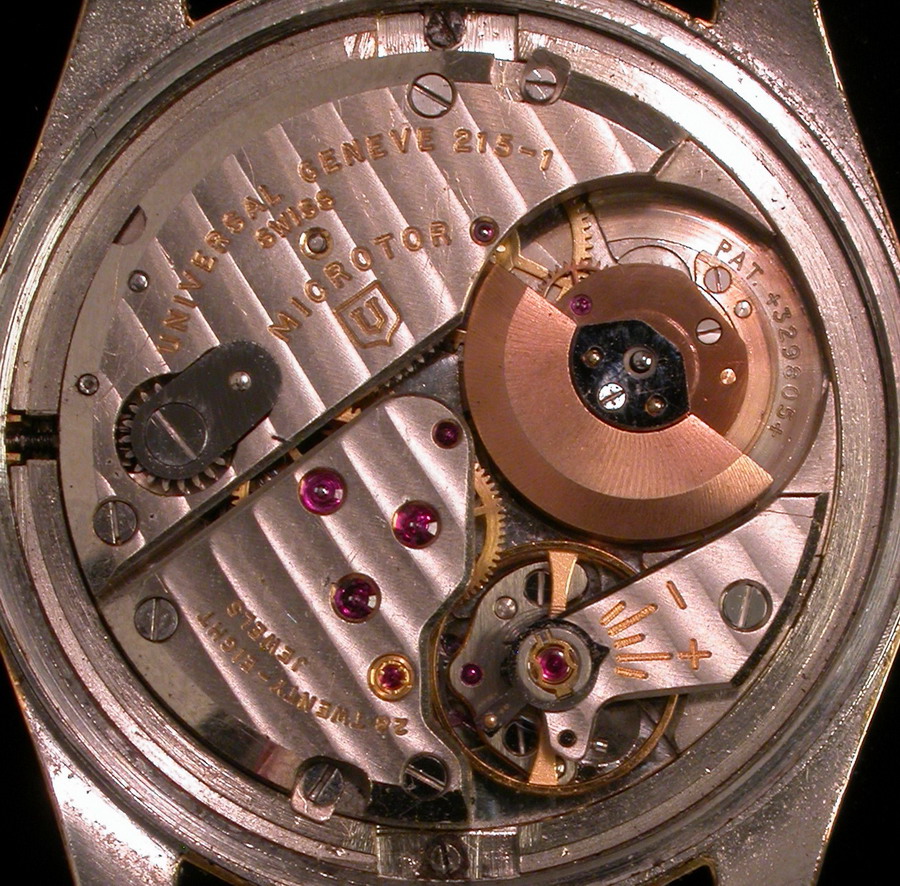

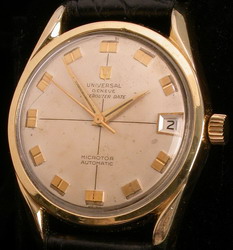

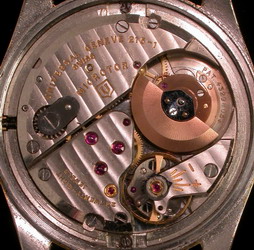

Universal Geneve. Microrotor

Rivals. In its microtor

movements, Universal Geneve used

a near-identical approach to that

of Buren. After a patent dispute,

Universal Geneve was required to

pay Buren a royalty fee on each

of its microrotor

watches. The

Beginnings The Caliber 12 /

Chronomatic movement had its origins in

the late 1950's when Charles-Edouard Heuer

-- then the President of Ed. Heuer &

Co. -- began to consider how the company

might produce an automatic chronograph.

Heuer studied the microrotor movements

being produced by Buren and began to

explore the idea of mounting a chronograph

mechanism on top of this movement.

The idea was

short-lived, however, as even the

combination of the thinnest Buren movement

and the thinnest chronograph mechanism

would be too thick to compete effectively

against the sleek watches of the era.

(Remember this was also the period of

Hamilton's "Thin-O-Matics"!)

All this changed,

however, in 1962, when Buren introduced an

even thinner microrotor movement -- the

Caliber 1280 "Intramatic" movement. With

the thickness of this movement reduced

from 4.3 millimeters to 3.2 millimeters,

it now seemed possible to build a suitably

thin automatic chronograph. At this point,

Heuer faced the question of who could

build this thinnest-possible chronograph

module, to be mated with Buren's base

movement. Dubois-Depraz Of the four

companies involved in the development of

the Chronomatic movement, Dubois-Depraz is

surely the company least known to the

public. Founded in 1901, Dubois-Depraz

didn't manufacture watches or movements,

and it didn't produce chronographs, but as

the leader in designing the so-called

"complications", Dubois-Depraz worked with

watch companies to make simple, base

movements into more complicated watches or

chronographs. Starting with a

simple time-of-day movement, Dubois-Depraz

had the ability to add a broad variety of

complications, including a chronograph,

power reserve indicator or calendar. Heuer

had called on Dubois-Depraz to develop the

movements for Heuer's 7700 series of

stopwatches. This work culminated in 1967,

with Dubois-Depraz's developing a special

module for Heuer's Monte Carlo stopwatch

(Caliber 7714), so that a single pusher

would simultaneously reset the minute and

second hands, as well as the hour

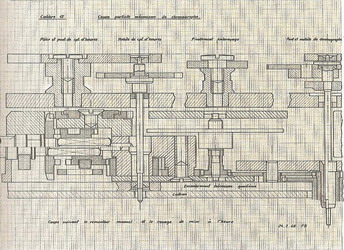

disc. The

Heart of the Partnership. Rather

than a traditional integrated

chronograph, the Chronomatic team

used a modular approach,

combining the Buren base movement

with a newly designed

Dubois-Depraz chronograph module.

This modular approach is

emblematic of the partnership

between the four firms -- Heuer,

Breitling, Buren and

Dubois-Depraz. Based on these

experiences, Heuer retained Dubois-Depraz

to study the feasibility of developing a

chronograph module that could be mated

with the Buren movement. Ironically,

Gerald Dubois (then president of the

company) had conducted comprehensive

research into the design of a chronograph

module to be used with the Buren

microrotor movements, and had discussed

the idea with Buren. When

Dubois-Depraz confirmed the feasibility of

this project, the Chronomatic venture was

almost ready for action. The Chronomatic

would be a 17 jewel lever movement,

consisting two essential elements

described as being "totally independent":

the Buren base movement (including the

self-winding and calendar mechanisms), and

the Dubois-Depraz chronograph module, a

plate holding a newly-designed chronograph

mechanism. In short -- a modular automatic

chronograph. Breitling Since its

inception in 1884, Breitling was known for

its production of chronographs and

precision counters for scientific and

industrial purposes. As Heuer was the

brand most closely associated with

automobile racers and racing, Breitling

became recognized as the brand most

closely associated with pilots and flying.

In the 1930's, Breitling began to produce

on-board chronographs for aircraft, and

also introduced the first two-button

chronographs, allowing the user to stop

and re-start the chronograph (time-out and

time-in functions). In 1942,

Breitling launched the Chronomat, the

first chronograph fitted with a circular

slide rule on the dial and bezel; 10 years

later, Breitling introduced its legendary

Navitimer, a three-register chronograph

equipped with a circular slide rule, as

well as a "navigation computer" capable of

handling all calculations called for by a

flight plan. At the request of

astronaut Scott Carpenter, Breitling

produced the Cosmonaute in 1963, a 24-hour

version of the Navitimer. Other Breitling

chronographs of the era included the Top

Time, Cadette, Unitime and Co-Pilot, all

designed for adventurers. Completing

the Partnership As Heuer, Buren

and Dubois-Depraz stood ready to embark on

the development of their automatic

chronograph, there was one last hurdle

between the venture and the commencement

of it work . . . this hurdle being the

capital required to fund the project.

Development of an automatic chronograph

would be a costly venture, more than Heuer

and Buren could undertake as two

relatively small, independent

companies. To address this

need, Jack Heuer (then President of

Heuer-Leonidas) did something unusual, for

the 1960's or for today. He approached his

friend Willy Breitling (then President of

Breitling) to discuss the idea of a

partnership. Though they were direct

competitors in their lines of chronographs

and stopwatches, Jack Heuer has explained

their cooperation on the Chronomatic

project in the simplest

terms. "Heuer was a very

strong brand in the United States and UK

markets, but weaker in Europe. Breitling

was strong in Italy and France, but had

little presence in the US or the UK. Both

of us needed an automatic chronograph; it

would be difficult for either of us to

develop it, working alone. This was a

perfect opportunity to create a

partnership in which both partners --

though entering as rivals -- could

strengthen their

positions." When

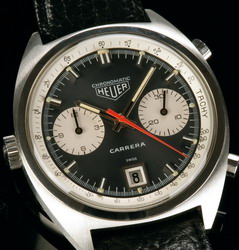

Rivals Became Partners. Heuer and

Breitling were direct competitors

in the market for sports

chronographs, but created a

partnership to develop the

Chronomatic automatic

chronographs. The Carrera and the

Top Time were both from the

mid-1960's. Breitling

courtesy of P.

Taubman. With

Dubois-Depraz having confirmed the

feasibility of building a modular

chronograph, and Breitling and Heuer

committed to funding this unique

partnership and sharing its output, Heuer

and Breitling then approached Buren with

their proposition of a partnership.

Joining the Chronomatic team was

attractive for a small company such as

Buren. Compared with the small customers

who bought Buren's movements, Heuer and

Breitling would constitute a significant

opportunity for Buren. With that, the

Chronomatic team was fully formed -- two

leading chronograph brands, the leading

manufacturer of thin automatic movements,

and the leading specialist in developing

chronographs and other

complications. Hamilton In 1966, while

development of the Chronomatic movement

was underway, Buren was acquired by

Hamilton Watch Company (of Pennsylvania).

Hamilton transferred much of its own

production to the Buren factory, in

Switzerland, and through the Buren

acquisition, became a partner in the

development of the Chronomatic movement.

While Heuer and Breitling were surprised

to have Hamilton as their new partner,

Hamilton had a limited history in the

production of chronographs and would not

represent a threat to the founding

partners, using only a small portion of

the movements produced by the Chronomatic

group. From

Thin-O-Matic to Chrono-Matic. It

was the Buren Intramatic movement

(used in this Hamilton

Thin-O-Matic watch) which allowed

the development of the Caliber 12

movement (used in this Hamilton

Chrono-Matic). Buren's microrotor

was at the heart of both these

movements. Project

99 The members of

the Chronomatic group realized the

importance of secrecy in their work. With

four partners in the group (and eventually

five), and a host of other companies that

would come to be involved in the

production of cases, dials and other

components, there were many people

involved in the day-to-day operation of

the project. Confidentiality was of utmost

importance, as the Chronomatic group raced

against unknown opponents to produce the

first automatic chronograph.

Throughout the

term of the project, employees of the

participating companies were prohibited

from uttering the phrase, "automatic

chronograph". Jack Heuer recalls that his

father, having served as a Brigadier

General in the Swiss Army, insisted that

the Chronomatic project have a code name.

With that, this unusual partnership became

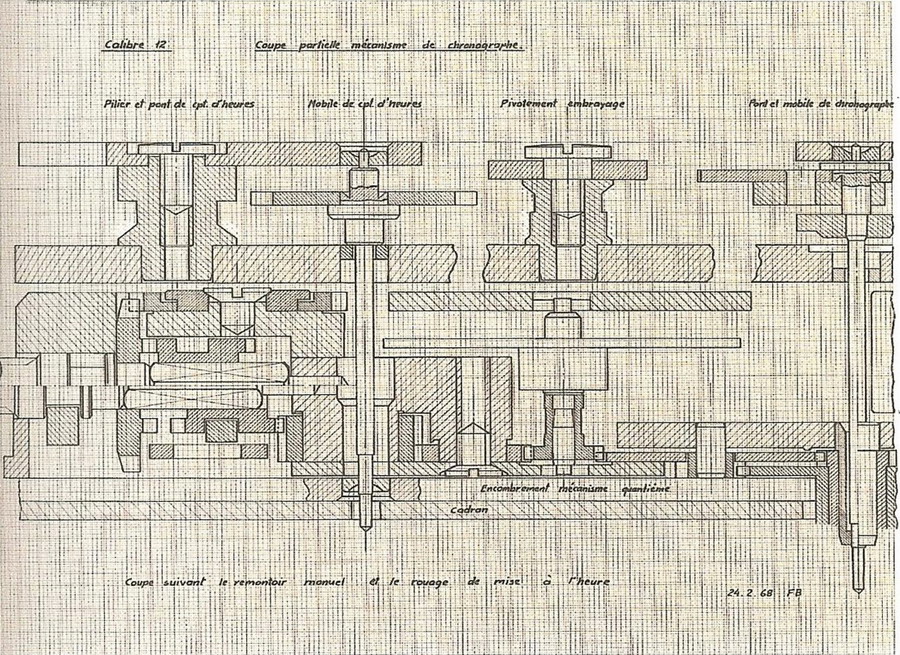

"Project 99". The

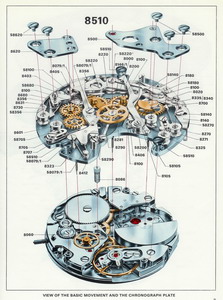

Laboring Oar. Dubois-Depraz had

the most challenging role in the

Chronomatic partnership,

developing a chronograph module

from scratch. The module relied

on levers and cams, in the place

of the chronograph's classic

column wheel. Of the four firms

participating in the development of the

Chronomatic movement, Dubois-Depraz had

the most challenging assignment. While

there would be relatively few

modifications in Buren's base movement,

Dubois-Depraz would develop the

chronograph module (to be known as the

8510 chronograph unit) from scratch.

Accordingly, Gerald Dubois, of

Dubois-Depraz, was the technical leader of

Project 99, and he also supervised the

development of the chronograph module.

Hans Kocher, who had developed Buren's

micro-rotor and served as its technical

director, and overall responsibility for

the base movement. The technical heads of

Heuer and Breitling also served as senior

managers of the Project 99 development

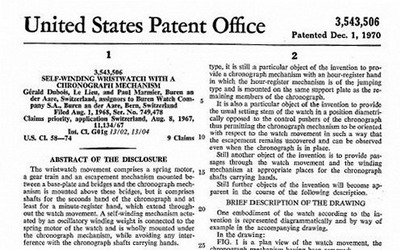

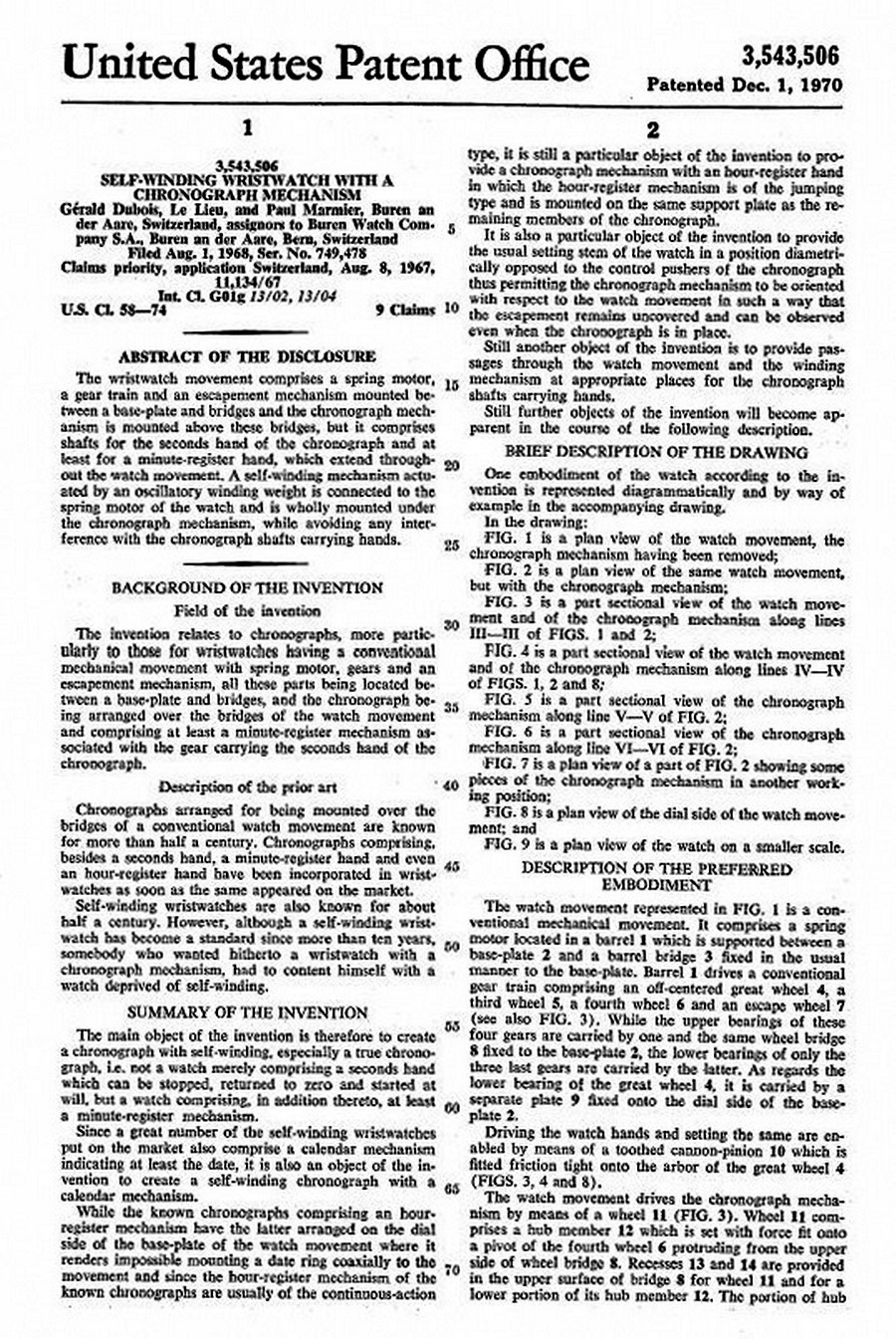

team. The

U. S. Patent Office issued Patent

Number 3,543,506, covering a

"Self-Winding Wristwatch with a

Chronograph Mechanism" to Gerald

Dubois, et. el. The Patent

application was filed on August

1, 1968, with the Patent being

issued on December 1, 1970. The

Patent documents include a

detailed description describing

the construction of the

chronograph, as well as detailed

drawings. To

see the Patent documents,

Click

Here.

While not deeply

involved in the technical design of the

Chronomatic movement, Heuer and Breitling

were responsible for designing an entirely

new series of cases and dials for the new

Chronomatics. Additionally, these firms

began to prepare for serial production of

the Chronomatics, which would involve

significant work for these companies.

In serial

production, Heuer and Breitling would

receive the base movements from Buren,

complete the assembly of chronograph

modules received from Dubois-Depraz,

combine this "sandwich" into a completed

movement, and then assemble the completed

chronograph. Indeed, each of the partners

in the Chronomatic group faced challenges

in the race to develop and launch the

world's first automatic

chronograph.

Which

Was First? Over the years,

there has been considerable confusion and

debate on what would seem to be the

relatively straightforward question: Which

company (or group of companies) was the

first to produce the automatic

chronograph? Was it the Chronomatic group

(led by Heuer and Breitling), the Zenith

venture (which now included Movado), or

Seiko? In fact, the

answer to this question may lie in the

precise manner in which the question is

phrased. Are we trying to determine which

company was first to publicly announce the

development of an automatic chronograph?

Or do we mean the public introduction of a

working sample of the watch? Or is it the

first company to display and demonstrate

production samples of the watch? Or will

we award the prize to the first company or

group that made automatic chronographs

available to the public, in retail

channels. And if we are considering

availability in retail channels, will we

consider chronographs offered only in a

company's home market or will we award the

prize to the company that offered

chronographs in multiple markets, around

the world? Let's roll the

clock back to January 1969, and try to

determine which company (or group of

companies) was first to announce,

introduce, produce, sell or achieve

worldwide sales of these automatic

chronographs. Zenith's

Announcement Zenith had begun

the development of its automatic

chronograph in 1962, hoping to release the

watch for its 1965 centennial. Work on the

project was suspended, however, so that it

took until December 1968 before Zenith had

its first prototypes. At that time, Zenith

planned to introduce its automatic

chronographs at the April 1969 Basel Fair.

As rumors began to circulate that the

Chronomatic group would show their

automatic chronographs before the Basel

Fair -- with these rumors likely

originating with companies supplying

components to the Chronomatic team --

Zenith decided to make a preemptive

announcement of its automatic chronograph.

Determined to be

the first to make their announcement, on

January 10, 1969, Zenith-Movado held a

small press conference in Switzerland, at

which they showed a working prototype of

their automatic chronograph (or perhaps

two or three samples). This was a local

press conference, covered only in local

and regional newspapers in Switzerland,

and news of Zenith's automatic chronograph

did not receive broad media attention.

The

First or the Third? With the

name, "El Primero", Zenith

declared that it was the first to

produce an automatic chronograph.

In fact, the Zenith was the third

automatic chronograph to achieve

serial production.

In any event,

Zenith reinforced its claim to having the

first automatic chronograph by calling its

new watch the "El Primero" (the "first").

However, these "El Primeros" only became

available to the public in October 1969,

making them the third brand to arrive on

the market (as described below). Still, we

can be certain that in January 1969, the

Zenith-Movado team publicly announced and

showed a working sample of the first

automatic chronograph. Whereas the

Chronomatic was as a modular movement, the

Zenith movement (caliber 3019 PHC) was a

traditional integrated movement, with a

classic column wheel. The movement ran at

a high beat of 36,000 vibrations per hour,

allowing timing of intervals as short as

one tenth of a second. The Zenith

chronograph used the customary tri-compax

layout for a 12-hour chronograph, with a

date window located between four and five

o'clock. Reaction

from the Chronmomatic Group The Chronomatic

group had produced 100 prototypes of its

automatic chronographs by the Fall of

1968, with Heuer and Breitling each

allotted 40 of these pieces, and

Hamilton-Buren receiving 10.

(Dubois-Depraz used the remaining 10

prototypes for testing and development.)

In retrospect, the Chronomatic group's

production of these prototypes, involving

numerous companies that produced the new

styles of cases, dials, hands and other

components, was most likely to have been

the event that tipped off the Zenith team

that the Chronomatic was preparing for the

launch of their

chronographs. Monaco

Prototype. The Monaco on the left

is believed to be one of the

first 10 Monacos to have been

produced. The "Chronomatic" name,

the absence of a reference number

or serial number, and certain

details of the movement support

the view that this was from the

very first batch of Monacos. The

"midnight blue" paint appears to

have vanished, with only a few

traces remaining. A normal

production sample of the Monaco

is shown on the

right. According to Jack

Heuer, there were two distinct phases in

the Chronomatic group's reaction to

Zenith's January 1969 announcement. The

Chronomatic team was surprised by the

announcement, and at first there was shock

and disappointment that Zenith was

claiming to have won the race, merely by

showing a small number of prototypes.

Soon, however, those involved in Project

99 were convinced that the Zenith-Movado

group did not have production samples of

their automatic chronograph, and that the

small, local press conference was a weak

attempt to show that they had produced an

automatic chronograph, when in fact they

were some months away from serial

production of these watches.

Any competition

from Zenith was further mitigated by the

fact that Zenith was a relatively

small-scale producer of chronographs at

this time, and did not pose a competitive

threat in many of the most important

markets (for example, Zenith was unable to

sell watches in the United States because

the Zenith Electronics company had prior

use of the name). Accordingly, the

Chronomatic Group chose to largely ignore

Zenith's announcement, and proceed with

its own plans to introduce the world's

first automatic chronograph, as if nothing

had happened on January 10,

1969. The

Introduction of the

Chronomatics If the Zenith

announcement was a low-key, local event,

the flamboyance of the Chronomatic group

in announcing the arrival of their

automatic chronograph was at the opposite

extreme. On March 3, 1969, Heuer,

Breitling and Hamilton-Buren held press

conferences at the Intercontinental Hotel

in Geneva, Switzerland, and the PanAm

Building in New York City, with a large

group of media present at these press

conferences. Additional press conferences

were held in Tokyo, Hong Kong and Beirut.

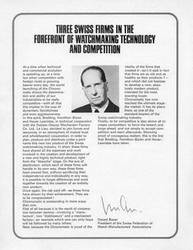

Mr. Gerald Bauer,

President of the Federation Horlogere

Suisse (the Swiss watch industry's trade

association, known as the "FH") was the

keynote speaker at the Geneva press

conference, with another FH officer making

remarks at the New York press conference.

Prototypes of the Chronomatics were shown,

and some lucky members of the audience --

selected by a drawing -- even went home

with the very first samples. These March

3, 1969 press conferences were a sensation

for the Swiss watch industry - the era of

the automatic chronograph had

arrived! For today's

researcher seeking perspective on the race

to introduce the first automatic

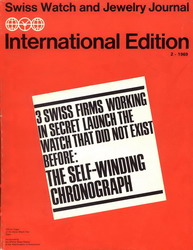

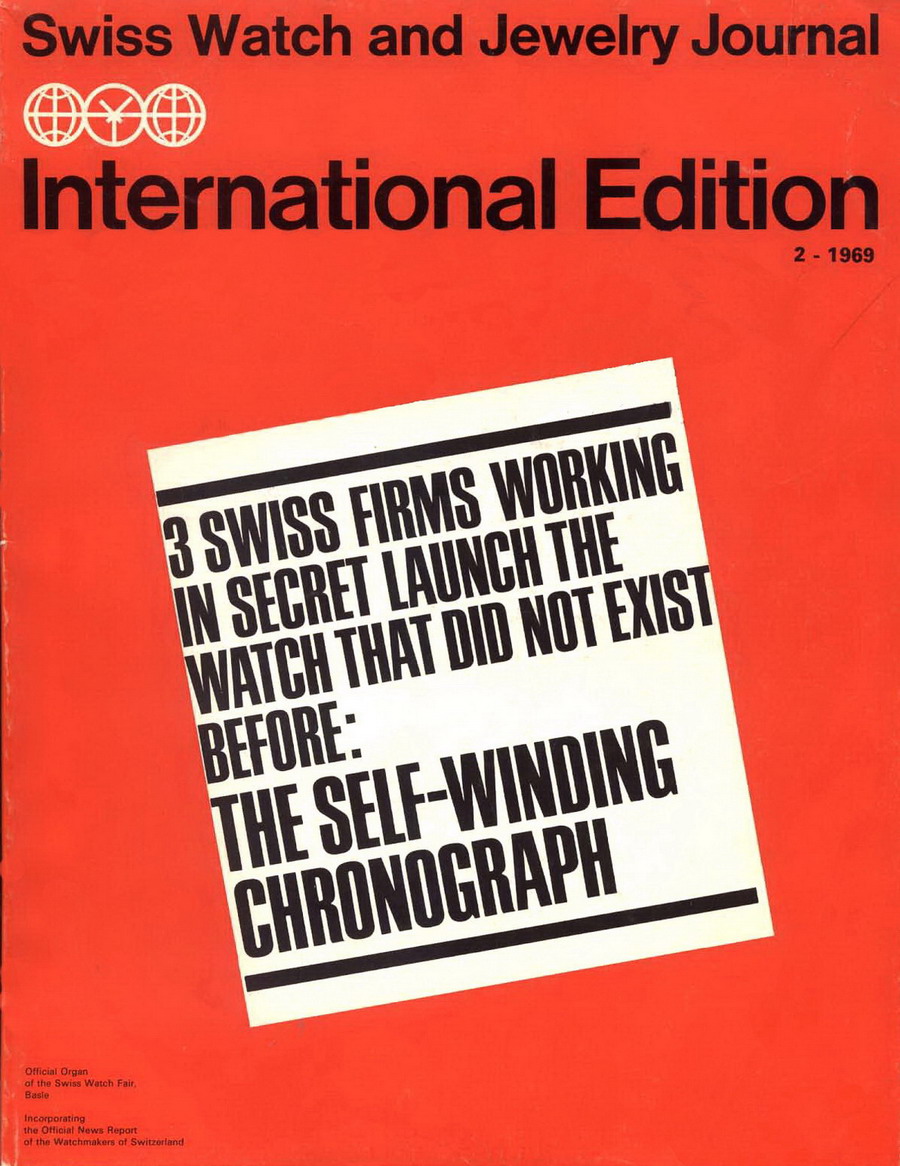

chronographs, the March 1969 issue of the

Swiss Watch and Jewelry Journal ("SWJJ")

witnesses the coronation of the

Chronomatic project, a celebration of the

victorious Heuer / Breitling /

Hamilton-Buren partnership. The front

cover proclaims that a "secret project"

has resulted in the launch of a new type

of watch, the "self-winding chronograph",

and the hyperbole increases from

page-to-page. The

March 1969 Issue of the Swiss

Watch and Jewelry Journal. Click

the left panel, to see the cover.

Click the middle panel, to see

the advertisements from the

magazine. Click the right panel

to review the articles about the

Chronomatic that appeared in this

issue. In six pages of

editorial content, we read of the Swiss

watch industry reasserting its "supremacy"

through a revolution in watchmaking, with

"wild excitement" about the modular

approach. The President of the Swiss

Federation of Watch Manufacturers'

Associations described the "courageous

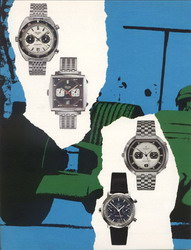

realism" of the partners. Eight pages of

advertising by the three manufacturers add

to the frenzy, with a dominant theme being

that consumers will no longer need to

decide between an automatic watch and a

chronograph -- now they can have both,

with the Chronomatics. Heuer

launched its Chronomatic /

Caliber 12 chronographs with

three models -- Carrera, Monaco

and Autavia. Click on the image

(above) to see the press release

issued by Heuer Time Corp. (the

Heuer-Leonidas United States

subsidiary), announcing the

introduction of these three

chronographs. Compared with the

splash made by the Chronomatic group in

the March 1969 issue of the SWJJ, with six

pages of coverage and eight pages of

advertisements, Zenith's presence in this

periodical seems almost sad. Six sentences

announce that Zenith will - at some

unspecified date -- be offering two models

of its automatic chronograph; a single

advertisement shows one

chronograph. The

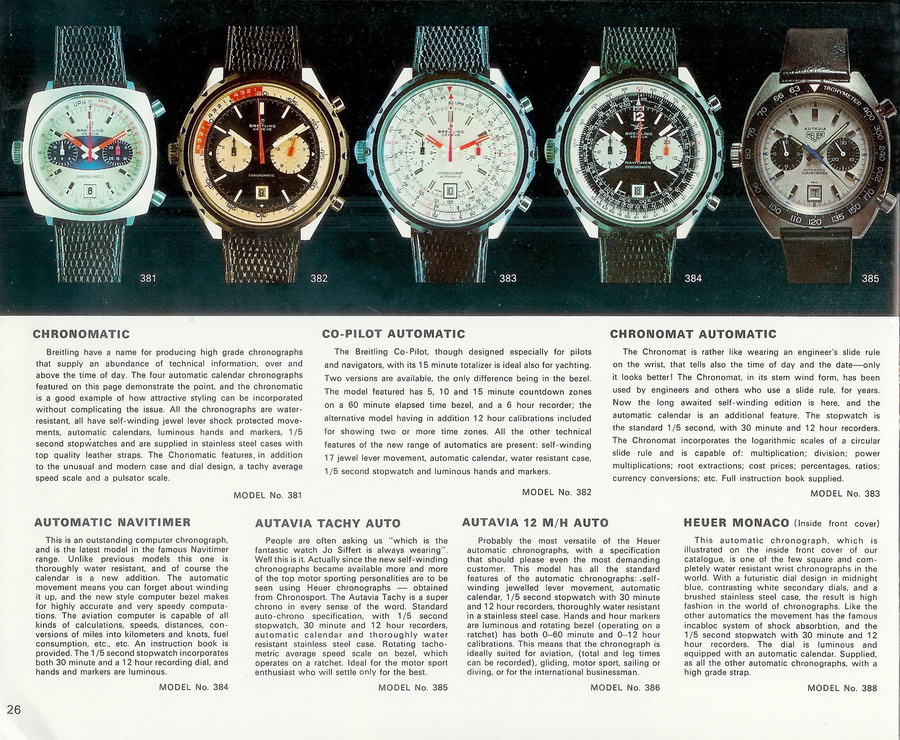

1969 Basel Fair The next event on

the timeline of automatic chronographs was

the Basel Fair, held in April 1969. At

this event, the members of the Chronomatic

group were able to show their dozens of

pre-production samples of Chronomatic

watches powered by the Caliber 11

movement, with multiple models from Heuer,

Breitling and Hamilton, in a variety of

cases and colors. By contrast, Zenith had

only two or three samples of their

automatic chronographs. First

to Market. This page, from a 1970

Chronosport catalog, shows the

great variety of automatic

chronographs offered by Heuer and

Breitling. Each brand offered

several models, that included a

variety of case shapes and sizes,

color schemes, and

functions. Looking back on

this Basel Fair, Jack Heuer remarks, "It

was the 1969 Basel Fair that convinced

Heuer and Breitling that we were - in fact

-- several months ahead of Zenith in the

real race, the race to provide these

automatic chronographs to members of the

public. For us to have 100 working samples

for over six months, compared to Zenith's

two or three, left little doubt that we

were far ahead in the race to get these

watches into the market." Seiko's

Automatic Chronograph As the details

relating to the achievements of the

Chronomatic group and Zenith-Movado have

come into some focus, it is far more

difficult to pinpoint when Seiko

introduced its first automatic chronograph

or when Seiko made this chronograph

available to the public in retail

channels. (Almost inexplicably, "A Journey

in Time", an authorized history of Seiko,

published in 2003, makes no mention at all

of Seiko's first automatic chronograph.)

Mr. Jack Heuer

recalls, "At the Basel Fair in April 1969,

Mr. Itiro Hattori, then President of

Seiko, visited our display, and extended

his congratulations to the Heuer Company,

upon our launching of the world's first

automatic chronograph. There was certainly

no mention of Seiko having an automatic

chronograph. In retrospect, this may have

been the most important acknowledgement of

our accomplishment." According to

current sources at Seiko, the company

launched its reference 6139 automatic

chronograph for the Japanese market in May

1969. It remains unclear, however, whether

this "launch" was merely a press event

(parallel to Zenith's January 1969 event),

or whether samples were delivered into

retail channels in Japan at that time.

Serial numbers, marked on case-backs of

the earliest Seiko Reference 6139

chronographs, indicate a date of March

1969. Again, one can only speculate about

whether these were pre-production models

or the first pieces of Seiko's serial

production for the Japanese market.

The

Mystery Remains. Seiko claims

that it launched its automatic

chronograph in May 1969, but

details of the launch are

unclear. Adding to the mystery,

the first two digits of the

serial number, "9" and "3",

indicate production in March

1969. The earliest

Reference 6139 chronographs were called

"Speed Timers" and had a 30-minute

chronograph recorder, with a day-date at

three o'clock. The red-blue outer bezel

was marked with a tachymeter scale; a

rotating inner bezel marked elapsed

minutes. Worldwide distribution of these

chronographs, along with additional

models, appears to have come by the end of

1969. Serial

Production Shortly after the

close of the Basel Fair in April 1969,

Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton-Buren

delivered their 100 Chronomatic samples

(pre-production prototypes) to their most

important distributors, and advertising of

their new automatic chronographs went into

high gear. By the summer of 1969, these

firms achieved full serial production of

their Chronomatics, with these watches

being broadly available to members of the

public, in the world's major retail

markets. These

are two Heuer Chronomatics from

the earliest production. The

Autavia (left and center) was

sold to a retail customer in

August 1969, and may be one of

the first Chronomatics sold at

retail. Photos

courtesy of Arno Haslinger, from

his book, Heuer Chronographen,

Callwey 2008. Ironically,

Zenith's "El Primero" appears to have been

the third automatic chronograph to achieve

serial production, with retail

availability in October 1969 and a limited

number of watches produced in the final

months of 1969. Zenith's advertising from

1969 seems to admit to the brand's second

(or third) place finish, claiming only to

be the world's first "high frequency"

automatic chronograph. A footnote to all

this: As between the Chronomatic group and

Zenith, the question of "who won the race"

may be complicated by the fact that Heuer

and Zenith are both currently owned by the

same parent company (LVMH). Currently,

marketing materials for Zenith indicate

that the El Primero was "the first

automatic integrated chronograph movement,

capable of measuring short time intervals

to a tenth of a second". By contrast,

current marketing materials from TAG-Heuer

describe the Caliber 11 as "the first

modular automatic chronograph". So while

the two companies battled, during 1969, to

become the first company to produce an

automatic chronograph, four decades later

they each seem satisfied to limit their

claims to that which cannot be debated -

that they each produced the first

automatic chronograph - one being

integrated and one being

modular! So

Who Won the Race? Thirty-nine years

later, there is no simple answer to the

question of who produced the world's first

automatic chronographs. We can say that

Zenith tried too hard, making a preemptive

announcement in January 1969 and invoking

the name "El Primero", when in fact the

company was months away from beginning

production or sales of its automatic

chronographs. By contrast, Seiko may not

have tried hard enough, with the company

remaining quiet in the spring of 1969,

even as its factory was beginning to

produce automatic chronographs for the

Japanese market. Despite these

shortcomings of Zenith and Seiko, each of

the firms - and their modern-day

enthusiasts - is left with at least some

basis for claiming to have been

first. Returning to the

perspective that we employed at the outset

of this series -- the question of which

chronographs first worn by the racers, the

pilots, the divers, the adventurers and

the sportsmen -- the answer to the

question of "Which was first?" becomes

clear. This

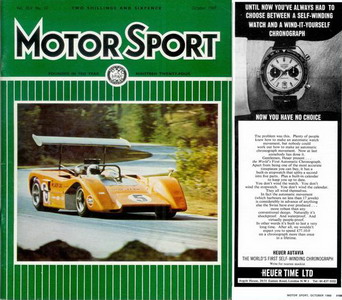

advertisement, from the October

1969 issue of MotorSport, is the

first print advertisement that

I have found, for the

Caliber 12 / Chronomatics. This

timing is consistent with the

conclusion that the Chronomatics

were first sold at retail

beginning during the Summer of

1969. Without any

doubt, it was the Chronomatic automatic

chronographs produced by Heuer, Breitling

and Hamilton-Buren that were first to be

delivered to these enthusiasts in markets

around the world. Accordingly, as we look

back at the end of the race, we see the

members of the Chronomatic group atop the

podium, celebrating their hard-fought

victory. It was a grueling race, not

decided until the last laps, but now the

members of the Chronomatic team cheer and

douse each other with champagne, as the

two rival firms can only watch, a step

down, on either side of the

victors. In Part Three of

this series, we will review the

chronographs that have been powered by the

Chronomatic movement, and also describe

the evolution of the Caliber 11, Caliber

12, Caliber 14 and Caliber 15 movements.

Special thanks to

Jack Heuer and Hans Schrag for their

contributions to this article. Jack Heuer

joined Ed. Heuer & Co. in 1958, and as

president of Heuer-Leonidas he was

responsible for the development of the

Chronomatics. Hans Schrag joined Heuer as

a watchmaker in 1963, and has worked on

the Chronomatic movements since their

introduction in 1969. Both these gentlemen

have been generous in sharing their vast

knowledge of the

Chronomatics.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

<

<

<

<

<

<